Owning a home is part of the American Dream. While it goes hand in hand with the social idea of raising a nuclear family, the economic value of owning a home brings security. Historically, the value of a property has almost always increased over time. “Even with modest inflation of 5 percent a year, a typical house will be worth more at the end of a 30-year mortgage than the purchase price plus all interest, taxes, and insurance combined” (NY Times).

However, the American homeownership rate peaked at 69.20% in the second quarter of 2004 and dropped to below 63% in 2016 (Trading Economics). While the homeownership rate is rising again, the trend of the past decade shows a clear decrease in homeownership. Simultaneously, the Case-Shiller Index has been increasing over the same period. The Case-Shiller Index is a lesser-known economic indicator that “tracks changes in the value of residential real estate, both nationally and in 20 metropolitan regions” (CNBC), and can explain homeownership rates and construction rates in the economy. The Case-Shiller Index is calculated by measuring changes of single-family homes by comparing the sale prices of the same properties over time (Investopedia).

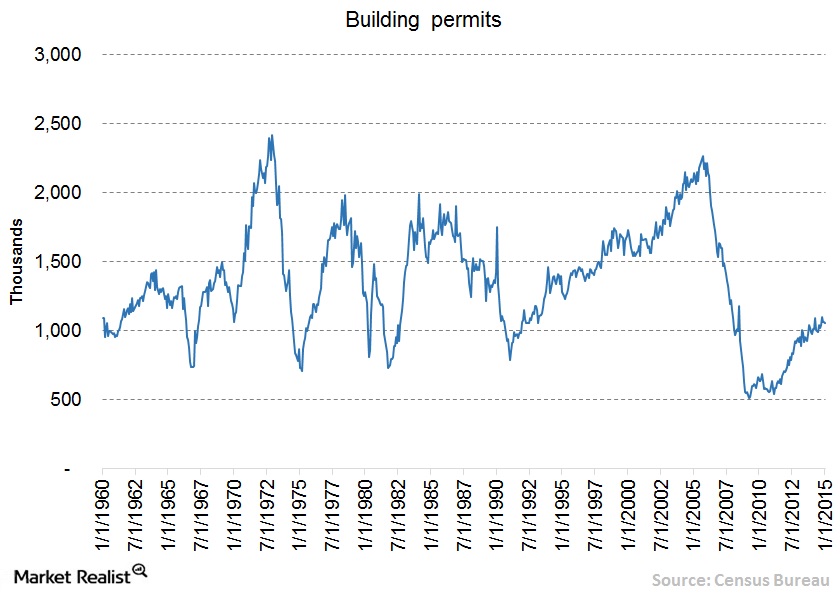

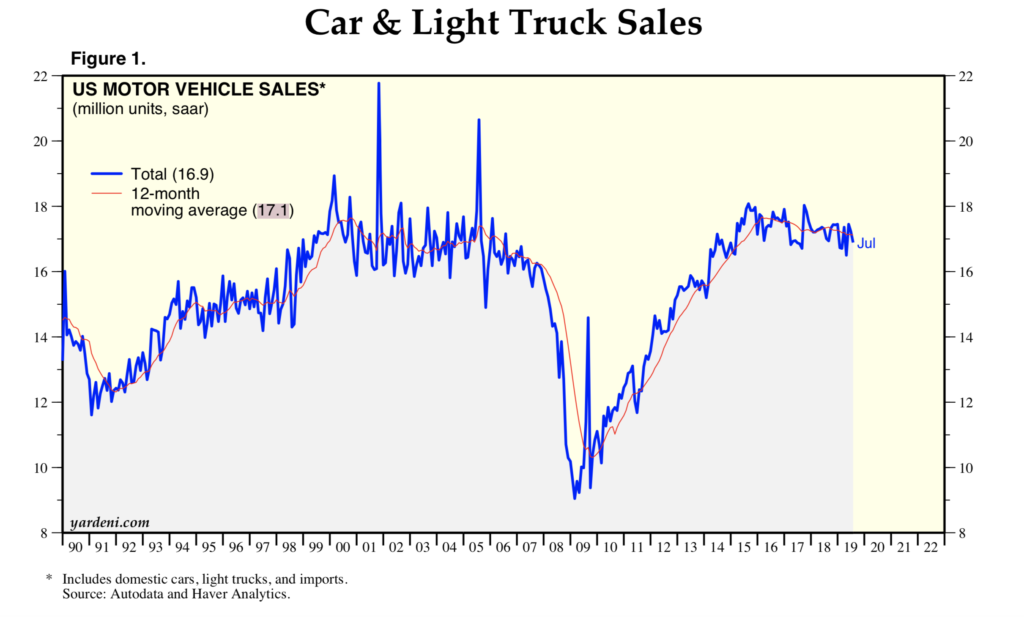

The increase in the Case-Shiller Index means an increase in home sale price, which can lead to fewer people being able to purchase a home. This result is usually related to a low supply and high demand for housing which encourages developers to create new housing units.

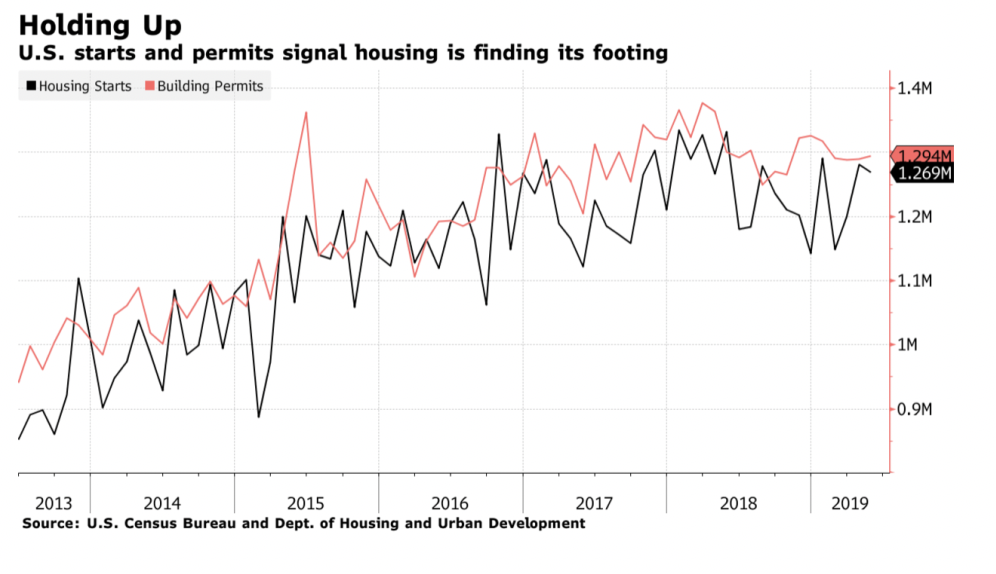

Let’s take a closer look at how the Case-Shiller Index impacts specific communities and reflects the state of the community’s economy–specifically in the San Francisco Bay Area. The most recent Case-Shiller Index in the San Francisco Bay Area reads 270.23 index points––this measurement is double the value in 2012. The resale value of homes has skyrocketed, and the homeownership rates are plummeting. According to The Mercury News, as of July 2019, “homeownership in the Bay Area hit a seven-year low last quarter,” coming out to be 51.7%. Homeownership in the Bay Area is extremely expensive due to the strong demand for housing in the Bay Area, however, it has encouraged an increase in supply. It led to a construction boom in the Bay Area for housing that has since slowed. In the years 2016-2019, there have been close to 14,000 units or homes built in San Francisco (SF Chronicle), but the start of new construction has slowed dramatically. Reasons cited include “a combination of higher construction costs, escalating fees, a softening market and increased interest rates has persuaded many builders to wait on the sidelines” (SF Chronicle). Now developers are saying that “projects with a projected price of $1,300 or $1,400 per square foot are not worth it to developers,” but projects above the $2,000 per square foot price point will be built (SF Chronicle). This means that even as new construction occurs, it won’t contribute to the desperate need for more affordable housing in the Bay Area. However, in June, Google promised $1 billion to create new housing units to alleviate the Bay Area housing crisis. They have pledged their money to develop 15,000 new homes and contribute to affordable housing, too (LA Times). The drop in overall home construction permits is the “start of a worrisome trend” (Mercury News). Not only will people continue to struggle to afford housing but the halt on construction projects puts people out of jobs as well.

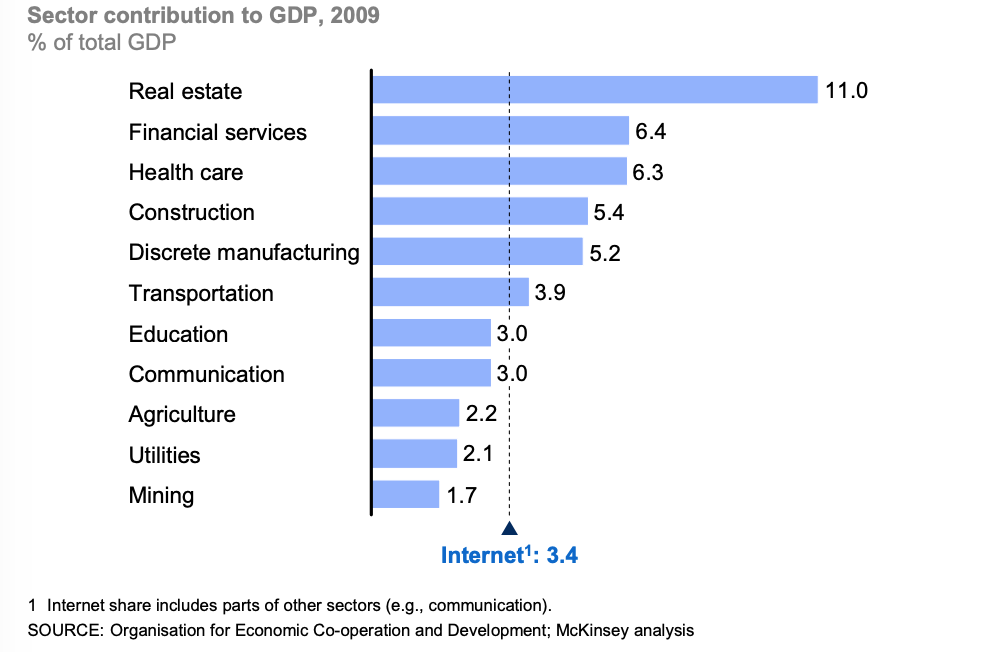

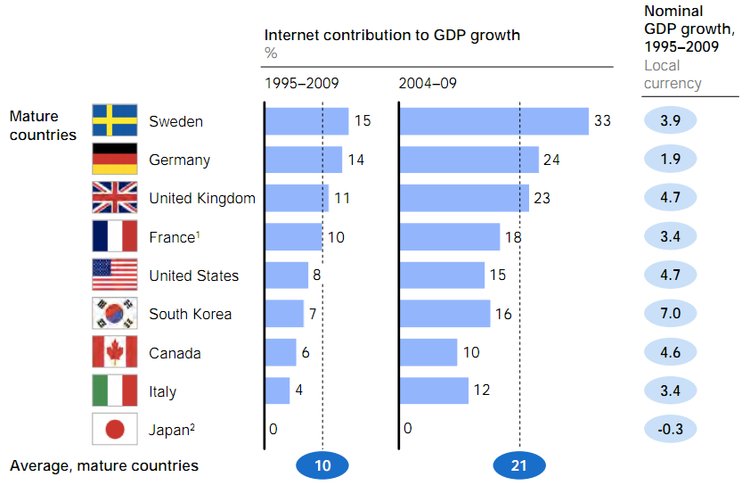

Regardless, the Bay Area economy will continue to boom because it is sustained and backed by the tech industry. Even if the Case-Shiller Index continues to rise in the Bay Area, the tech industry will continue to supply high wages and residents will continue to pay the inflated prices. This scenario applies to the people employed by the large tech-giants. People who are caught in the Bay Area without high wages will struggle to afford housing, but the overall economy will still excel based on the spending and circulation of high wages.