Last year, Aramco became the world’s most profitable company. It made $111.1 billion in net income. To put this into perspective, Apple made $59.53 billion, Amazon $10.07 billion, Alphabet Inc. (Google) $30.73 billion. Aramco made more than all of the aforementioned combined.

Aramco is a state-owned enterprise. Though, it is privately managed. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS) announced that the company would go public. This offering is just a small step in his Vision 2030 plan. An economic and cultural diversification plan that has already made results both economically and culturally.

MBS had a goal of the company’s valuation being as high as $2 trillion. No company has ever planned to go public at such a high value before. The company since then has been re-evaluated after a roadshow in the Gulf region. It is expected to be valued at $1.6-$1.7 trillion.

The plan for the company now is to go public on the local market by December 4 with the aim to go international. Aramco is set to sell 1.5 percent, 3 billion, of its total shares (the rest belonging to the government of Saudi Arabia) at $8-$8.52. Additionally, the company announced a “bonus share” option in which shareholders will receive additional shares if they hold the stock for a certain period. The company is expected and expects itself to surpass Alibaba’s historic IPO of $25 billion.

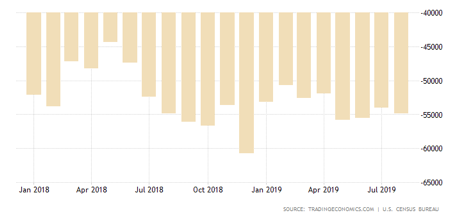

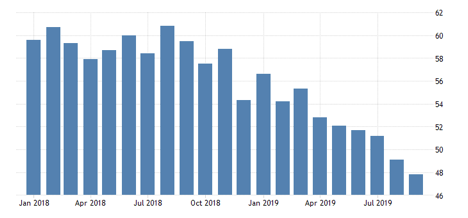

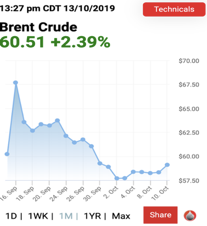

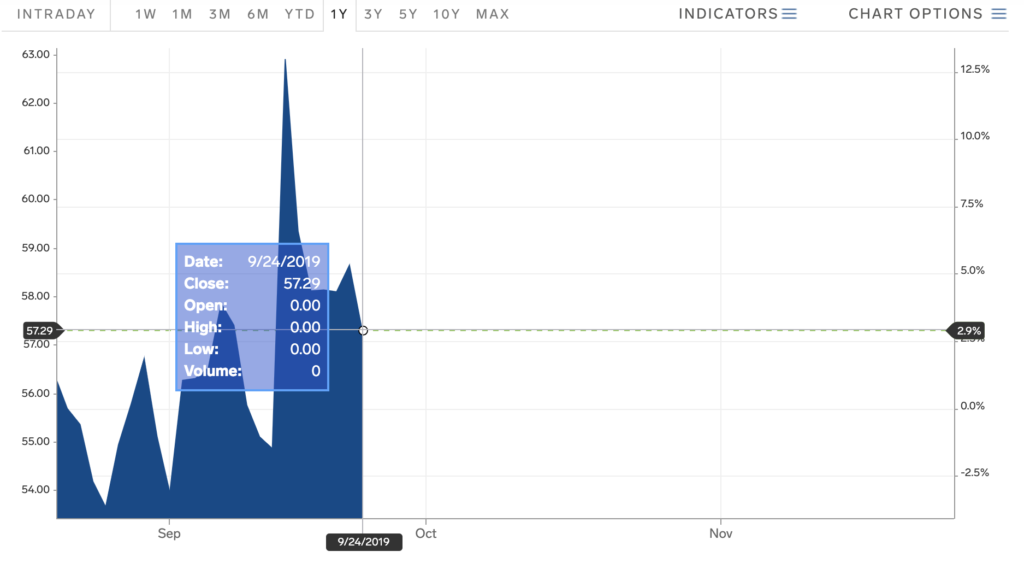

There is a caveat. Things do not look as promising this year. Profits until the end of September are down 18 percent year-over-year, $68 billion. This is largely due to volatile oil prices.

The reason investors seem interested in a company such as Aramco is the growing cashflows the company is able to generate in terms of dividends. Currently, the company plans to pay a dividend yield of 4.5 percent based on a $75 billion payout. The devaluation is a benefit to investors, too. A lower valuation means a higher dividend yield, which is what investors are seeking in a company that would be vastly controlled by the Saudi government.

Aramco originally set to go public last year in 2018 selling 5 percent of total shares to the public. The IPO plan was halted because it did not meet MBS’ evaluation of the company at the time. The public relations crisis that ensued when Washington Post columnist, Jamal Khashoggi, was murdered made foreign investors pull back. Also, it was delayed slightly this year as a result of the attacks it suffered by Houthi rebels in September.