The news over the past few months has been riddled with updates regarding the possibility of a recession. The yield curve has proven itself to be a reliable signal, as it successfully predicted the past seven recessions. However, viewing one part of a large, complex machine may not tell the whole story. Many other indices and sources of information should be taken into consideration when deciding whether or not a recession is likely.

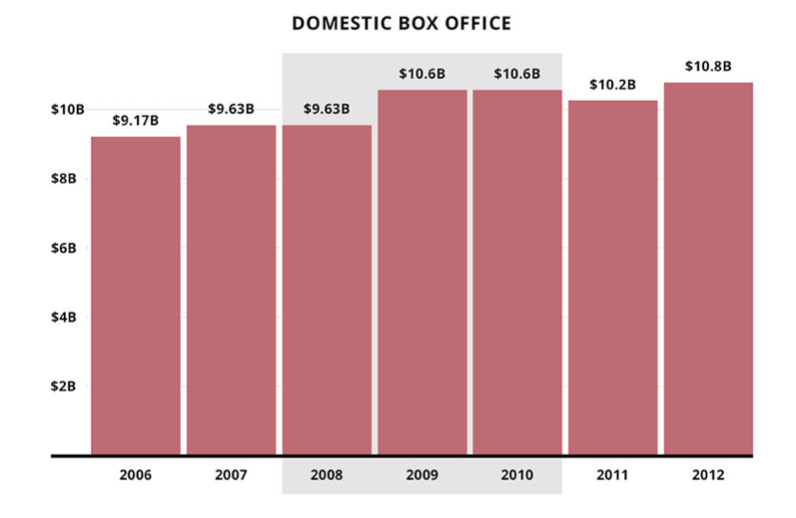

US Trade Balance

The tensions between the United States and China are an integral part of this puzzle. Greg Ip, chief economics commentator for the Wall Street Journal, explains that from 2000-2017 import tariffs were below 2 percent, but President Trump’s tariffs bring that figure close to 6 percent.

This has direct implications on the international logistics industry, too. Fewer goods being made due to higher prices leads to less demand on the delivery of such goods.

On September 18, 2019, Fedex announced reduced earnings and reduced forecasted profit and revenue. As a result, shares took a 13 percent dive in their prices to $150.91. This fall was the largest decline in share price the company suffered since 2009, as it lost $6 billion in market capitalization. CEO Frederick Smith attributed this loss to decreases in shipping volume to China, while CFO Alan Graf pointed at Europe.

The Trade Balance chart above details that the US is importing more than it’s exporting – hence the negative signs by the digits. Here, the farming industry is a rather large factor to these statistics.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the US’s largest agricultural export to China is soybean. Soybean accounts for $12.3 million in export revenue and 63 percent of agricultural exports.

Since China implemented tariffs on US soybeans, the price and export of soybean has plummeted. In September 2012, soybean prices reached an all-time high of $17.36 per bushel. The price of a bushel of soybean as of October 7, 2019 is $9.15.

Prior to the trade war, the US and Brazil had roughly the same amount of market share in terms of agricultural goods to China: approximately 40 percent. As of May 2019, the US has only 10 percent market share due to the tariffs imposed by China. That explains some of what is happening in the current negative trade balance.

Farmers are suffering as a result. It is predicted that farmers will lose $130 per acre after rent as a result of the tariffs. If they can’t sell their products, then they can’t pay for costs of any kind such as: rent, equipment, maintenance, sustenance, power. If farmers who don’t own their own land can’t pay rent, then they will have to relocate. That on its own is devastating to any farmer. To think that if farmers were evicted from their rented land in droves, one can easily think that agricultural real estate prices would crumble, unemployment would rise, and GDP would drop.

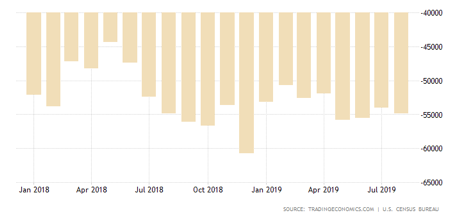

Purchasing Managers’ Index

While US exports decrease, new purchase orders have come to a screeching halt, as shown in the chart above. The editorial board of the Wall Street Journal says “uncertainty about demand, prices and tariffs is causing business to scale back new equipment purchases.”

The PMI has steadily decreased from 2018 and even more so in 2019. Using the data on the chart, 2018 averaged a PMI of approximately 58-59.

This year has, so far, seen the most contraction since the Great Recession.] January rang in the year with 56 percent. September registered a PMI of below 48 percent. This is a relative decrease of 15 percent.

When the months of 2019 are compared to the respective months of 2018, the difference is striking. August 2018’s PMI registered above 60 percent while this year’s August PMI registered below 48 percent – a 20 percent relative decrease.

Domestic logistics are feeling the pinch. As trucking companies nationwide feel strapped for cash, orders for new heavy-duty trucks fell by 79 percent. Since July 2019, the trucking sector has also slashed 9,600 jobs.

ACT Research president and senior analyst, Kenny Veith, said, “…there will be layoffs up and down the truck manufacturing supply chain as a result of falling demand.”

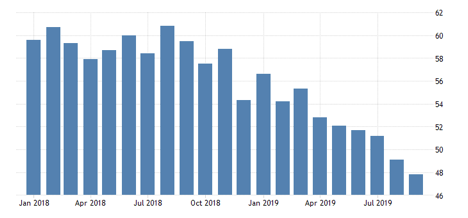

Manufacturing Production Index

Above is the latest Manufacturing Production Index. Declining over the past year, September was “the steepest month of contraction for the manufacturing sector since June 2009” due to the effects the US-China trade war had on imports, exports and the prices of raw materials.

While the US is facing contraction in manufacturing, purchasing and a trade imbalance, automotive manufacturing has been in the news recently. United Auto Workers’ strike has been an on-going disaster for nearly a month.

The strike started on Sept. 16, 2019, as a result of the expiration of its labor contracts with American automotive manufacturers. The union demands higher wages, healthcare, opportunities for temporary workers and profit sharing – General Motors (GM) achieved record profits of $2.4 billion in second-quarter earnings (a 1.6 percent increase from the previous year).

When 46,000 union workers go on strike, the cars won’t make themselves. GM is losing as much as $100 million per day as the strike continues. The effect of the strike is not limited solely to GM. It is destroying its home, Michigan. As the strike goes on, state income-tax revenue drops $400,000 per day.

The latest data shows the US produced 2.55 million units in August 2019, which was a drop compared to July’s 2.67 million units. The US automotive manufacturing industry reached its bottom point of 1.29 million units in January 2009 – the Great Recession. The disparity between the amounts of units produced in 2009 and 2019 is narrowing, and the US hasn’t officially gone into a recession yet. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates a 1.8 percent growth for the third quarter. The Bureau of Economic Analysis released its estimate on October 30: 1.9 percent.

Oil & Geopolitics

While the US-China trade war is an intertwined battle of politics and economics, geopolitical matters also have huge sway on markets. Above is a chart from www.oilprice.com that displays Brent Crude oil prices over the past month. The beginning of the chart shows a spike in prices from approximately $60 to $67.50 per barrel during mid-September. This spike was a result of a supply shock after Saudi Aramco’s facilities were attacked by foreign agents. These attacks disrupted 5 percent of global production. Ip claims that “investors and economists see supply shocks as a threat to growth.”

Brexit is another international matter that has American investors on-edge. Nobody can see the future or reliably predict the outcome of Brexit – whether deal or no-deal. Brexit has serious implications to supply chains and financial markets. Goods won’t transport as easily and people can’t travel as conveniently, and that affects overall production and output.

As Jon Hilsenrath and Josh Zumbrun of the Wall Street Journal, say, “businesses react to uncertainty by pulling back on investment and employment, and a slew of economic data in recent months strongly suggest the theory has become reality.”[

Hilsenrath and Zumbrun go into detail about this data in their article. August 2019 saw a fall in job openings of 7.5 percent. They also mention truck and heavy machinery orders facing a decrease, which was briefly explained in the PMI section. British demand on American goods has decreased by 2.6 percent in the past year, which was made evident by US export data.

On top of

the US economy’s internal contraction, international disruptions of this

magnitude send the US economy into a panic mode. This psychology further

affects the economy, as everyone believes that it’s going awry. As mentioned

above the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates third-quarter results at 1.8

percent. The BEA estimates third-quarter results at 1.9 percent. Seeing as both

those number are lower than Q2’s 2.1 percent, it seems as though all indicators

officially point to a recession.