Instead of trying to predict the future economic outlook of today, this blog takes on a retrospective stance on European economic growth from the 14th-16th centuries.

In the 1340s Italian ports in Genoa and Venice thrived on trade and commerce. Traders from Asia were a regular sight, bringing spices and other luxury commodities from distant lands. It was a time of relative prosperity; however, within a couple of years, Europe would live through its worst plague epidemic, Black Death, that would ultimately wipe out roughly a third of the European population and change the course of its economy. In less than a decade more than 20 million people perished from the mysterious disease. Yet, amidst the chaos something interesting was brewing – wages started climbing rapidly.

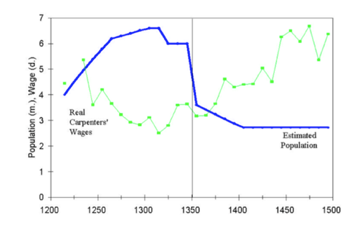

At the time of the feudal system, peasants rarely had any choice and no income mobility. The wages were low, and the cost of capital was high. The Black Death has suddenly swayed the odds in the peasants’ favor. In order to understand how the epidemic affected labor and wages, it’s crucial to understand the supply and demand framework. The supply and demand of labor rest at equilibrium, meaning that if the working population were to suddenly drop, labor would become scarcer and wages would rise, establishing a new equilibrium. As the population rapidly decreased, there were fewer labor units available. It was only logical for peasants to demand higher wages from their lords. Lords, in turn, had no choice but to pay more because the number of fields to plow, remained the same.

(Image cited from The Economist)

The wages were so high that England passed a law in 1349 forcing peasants to accept wages they received before the plague. As peasants gained more leverage, many lords were forced to give them broader freedoms and better working conditions. This time period of high wages became a milestone that ultimately led to the dissolution of Feudalism altogether in the 16th century.

As the wages spiraled out of control so did the inflation. According to The Economist, within the first 4 years of the epidemic, the average wheat prices rose 300%. Nevertheless, the lords enjoyed higher profits as prices went up and the peasants appreciated higher wages. People in Europe now had more purchasing power and a stronger incentive to maximize the efficiency of production as labor costs piled up.

Although the European economy underwent a post-plague recession it has reemerged as an economic powerhouse a century later. New innovations stemmed from scarce labor, higher wages, and greater purchasing power. Novel double-entry bookkeeping revolutionized accounting processes while banking systems became more complex. The printing press was invented in an effort to balance out the high wages and labor deficit. Technological advancements in shipbuilding allowed for exploration and unprecedented trade growth.

The Black Death was a horrifying time period in Europe which severely damaged the economy. At the same time, its side effects spurred immense growth within the region. Labor scarcity and high wages might have not been the sole ingredients in such a change, but they certainly had encouraged innovation in different practices and altered the societal structure which set Europe on the path of progress.

Sources:

http://msh.councilforeconed.org/documents/978-1-56183-758-8-activity-lesson-15.pdf

https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economic-impact-of-the-black-death/

https://theconcourse.deadspin.com/after-the-black-death-europes-economy-surged-1821060986

https://www.economist.com/free-exchange/2013/10/21/plagued-by-dear-labour

https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Italian_Studies/dweb/plague/effects/social.php