Big tech money is chasing the development of self-driving trucks. Google, Uber and Tesla are investing heavily in this technology and a new autonomous truck startup called Embark has already pulled in $17 million of series A funding.

Though Silicon Valley is pouring money into self-driving trucks, it’s hard to tell when this technology will become widespread and cause an economic dislocation for a significant part of the American workforce.

Accurately pinpointing a time frame for when this disruption will occur is important for trucking, its related industries and consumers. But there are many variables that still need to be accounted for when estimating how many years it will realistically take for these trucks to become widespread.

Because of the inherent uncertainty in self-driving trucking projections, it is unclear how immediate the labor problem is. According to an Obama-era White House report, two million trucking jobs out of 3.27 million are already threatened. Automation is going to happen, but when it does and the extent to which it will affect jobs is up in the air, said University of Pennsylvania professor of economic sociology, Steve Viscelli.

“There’s a dichotomy of it’s [automated trucks] either never going to happen,” Viscelli said, or automation could happen in the near term and create a trucking jobs crisis.

As of now, most truckers are still employed. But within three to ten years though, Viscelli says Google, Uber and Embark, along with other companies could surmount the difficulties that self-driving trucks are currently facing.

But Jerry Lake, who runs a trucking business with his son and wife out of small-town Montrose, Colorado, says the variables that he faces daily on the road are hard for a machine to predict and he thinks it’s a bad idea. He doesn’t see the complete switch to self-driving trucks happening as soon as Viscelli predicts or even happening at all.

“I don’t even know what the advantage is or what they are trying to accomplish other than the fact that they can do it,” Lake said. “Then you’re taking jobs away from people in America.”

For Lake’s local business, it doesn’t make any sense for him to switch to automation at all for his small fleet of two trucks.

First, retrofitting trucks for full automation is expensive. It costs about $23,400, according to the American Transportation Research Institute, and would not be cost effective for Lake’s business. Second, the specialized, localized trucking that Lake does requires extra knowledge of county and city roads, as most of the driving he does — 65 miles one way between Montrose and Grand Junction — aren’t on interstates.

Lake has trouble believing self-driving trucks can keep up with the monotony of long-haul trucking. “I have a problem with all the variables you run into — accidents and weather — that the truck can react in time and the drivers can’t always do that either,” he said.

Mapping roads in a way that is compatible with these trucks is another difficult variable to overcome. Google claims that they have mapped 99 percent of public roads in the United States, as of 2014; but that still leaves around 40 thousand miles of unmapped roads, or 8 round trips from L.A. to Miami.

Viscelli said basic sensor limitations hold back trucking as well. Most light detection and ranging (LIDAR) systems in use on these prototype trucks can only see three to four hundred feet in front of them. But driving at 55 miles per hour, it will take over 400 feet to stop a truck with an air brake system, according to the Department of Motor Vehicles. The automated system leaves no room for error and can pose a safety risk.

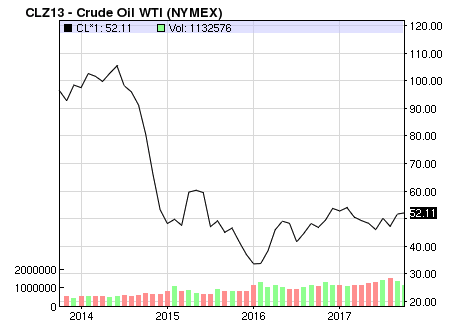

In an economic sense, the cost-benefit analysis doesn’t make sense yet. It will cost more to total a truck and possibly kill people on the road due to faulty automation programming or equipment than to deliver freight or a package without paying a driver.

At the same time, self-driving technology is making major strides in its development. Uber’s truck Otto transported 51,744 Budweiser cans for 120 miles between Fort Collins to Colorado Springs. The delivery had a police escort and a driver observed from inside the truck. Still, the proof of concept is rock solid.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qb0Kzb3haK8

The TraPac terminal in the Port of Los Angeles is completely automated; from the cranes to the four-legged trucks that load crates onto still human-operated tractor-trailers. And Long Beach isn’t too far behind. Amazon warehouses use robots instead of fork lifts and they are already working on using drones for deliveries.

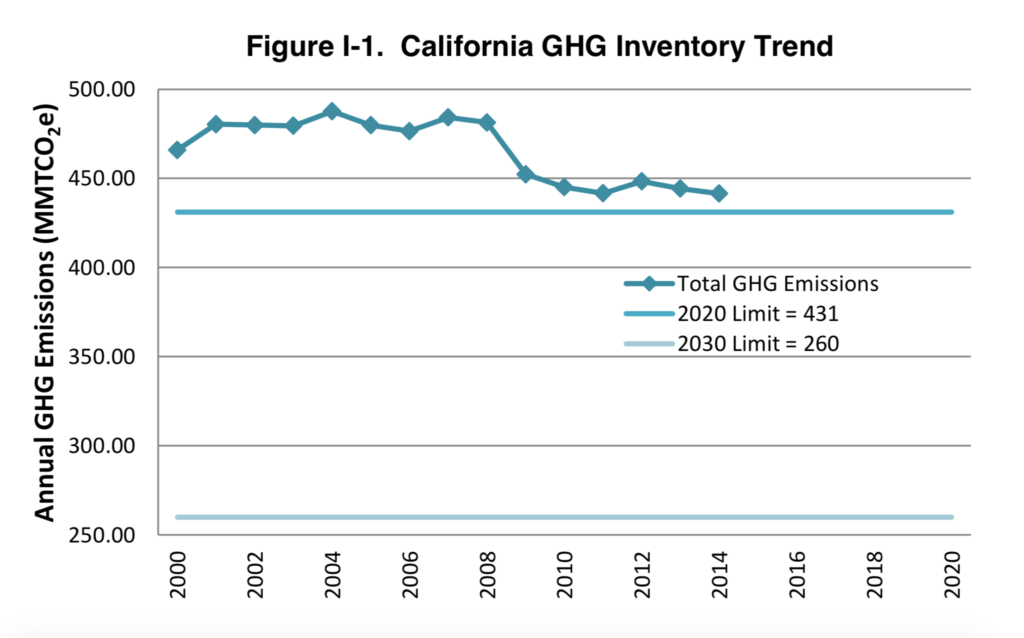

The manufacturing sector has lost around 8 million jobs because of automation (which was started by General Motors in 1961), globalization and the Great Recession from 2008 to 2010. Trucking could also displace a large majority of America’s workforce with the allure of a more technologically-oriented supply chain.

Not having to pay for driver’s wages and benefits will translate to lower prices in the store for consumers, but at the expense of a large portion of the population being unemployed and failing to reach their productive capacity.

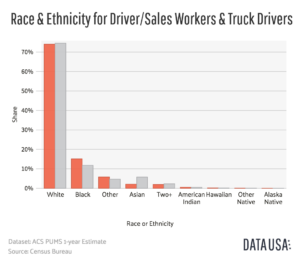

The trucking industry is dominated by white males with an average age of 45. Around 95 percent of people who work in the industry are male and 75 percent are white. That matches up surprisingly well with the rest of the U.S., which is 77 percent white. So if trucking were to ever be completely automated in any way at least 10 percent of America’s workforce will go away.

Truckers have won a small battle in U.S. Congress to ban legislation on self-driving trucks and cars that are under 10,000 pounds, but as more pressure from tech companies mount, it’s unlikely to hold forever.

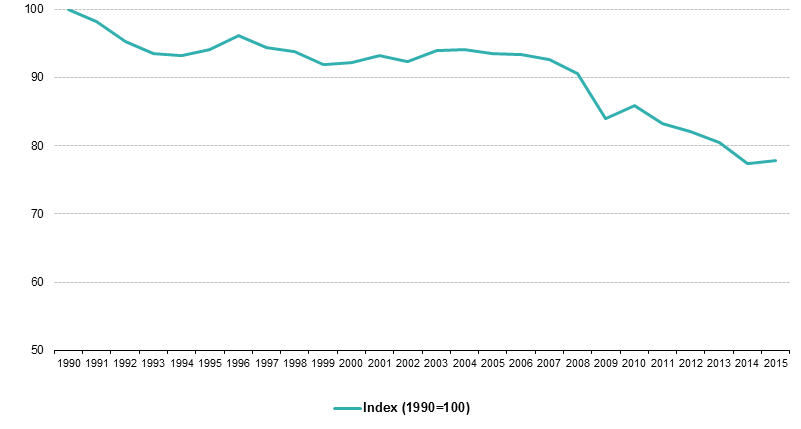

When self-driving trucks eventually become commonplace, the driver demographic will have trouble finding other work that requires higher level education. Most truckers don’t have college degrees, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And middle-aged drivers will find that university education has skyrocketed at a rate faster than inflation. In a Bloomberg report, college tuition and fees have increased 1,120 percent since 1978.

Plenty of other professions are at risk too. An Oxford survey predicted that 47 percent of jobs around the world will be taken by robots in the coming decades. And it’s probably going to hit truckers first.