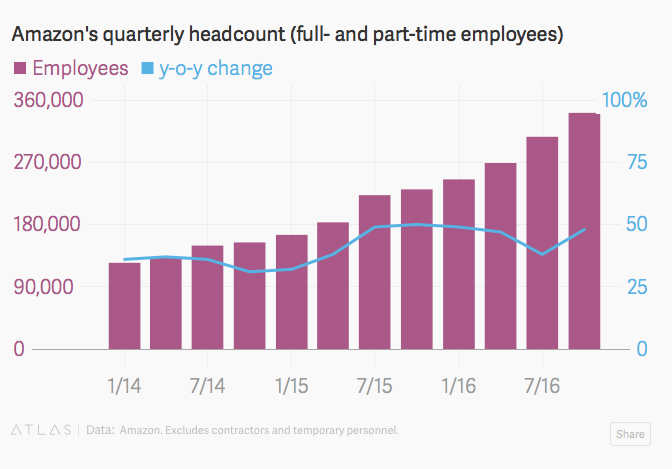

Amazon is expanding its workforce, which is 18 times larger than Facebook, in its growing fulfillment and distribution network, while at the same time bringing automation to almost every step of warehouse workflow.

There are currently 125,000 people working at Amazon’s warehouses, which comprise 90 million square feet across the United States, and the company is continually adding to that base with new personnel and technology.

Now, among human workers, there are an increasing number of robotic companions. Amazon acquired robot manufacturer Kiva Systems in 2012 for $775 million. Two years later, and under the name of Amazon Robotics, they rolled out their automated product, which carts items around the warehouse, ordered from across the country. That’s in addition to a whole host of other automated equipment, from robotic palletizers to machines that measure the correct amount of tape needed per box.

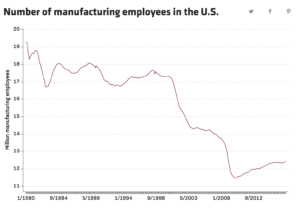

Amazon’s reliance on robots marks another shift in the labor market similar to the one that was seen after agriculture became automated and industrial tools became automated. In each case, new jobs were created to deal with labor displacement; the former in industry and the latter in the service-based economy. When robots eventually replace all humans in these warehouses, the roadmap to new employment isn’t so clear.

Therefore, figuring out how robots and humans will work together in the future can hedge against large scale layoffs and tough transitions into new jobs and unemployment. What Amazon is doing at their warehouses to make their trademark two-day shipping work is at the intersection between how machines and people can work together. Or how robotics can erase the human element. It will undoubtedly mold the future of the economy.

Automation, especially in the case of Amazon, can aid the workforce in many ways but it can also hurt Amazon’s labor by potentially displacing those 125,000 warehouse workers, and beyond that, the people that do deliveries.

Robots can help people increase their productivity and can benefit their health at the same time said Jennifer Miller, assistant professor at the Sol Price School of Public Policy and expert in economic development, science and technology policy and workforce policy.

Miller said that working in a warehouse is physically demanding without robots to do the heavy lifting. Some workers develop pain lifting boxes all day; others may have to walk as many as 10 to 13 miles a day.

“It’s the kind of work, in some ways, that could benefit from automation in that it’s not necessarily work that the workers doing it are finding [it] intrinsically satisfying,” Miller said. “They’re working for pay and in some cases taking a toll on their health.”

The robots make it easier for employees to do their work and it also increases overall efficiency, which is why Amazon is slowly adding these machines to its workforce while at the same time slowly paring down the human element.

Despite Amazon announcing that they employ more than one million people, robots are playing an even bigger role in their day-to-day operations. Last year, Amazon added 75,000 more robots, the majority of them being Kiva bots. That brings their total automated units to one-fifth of all company employees.

These robots cut down the time it takes to get an item off a shelf and into a box from 90 minutes to 10 to 13 minutes. It also increases storage space by 50 percent because the Kiva bots can line up right against each other.

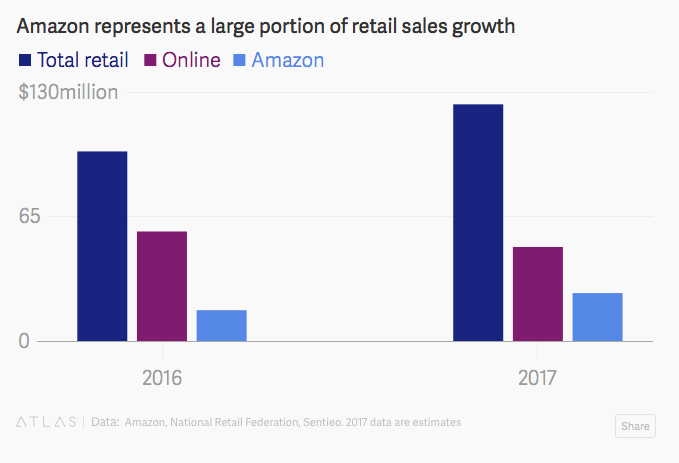

Without automation, Amazon would have difficulty satiating customer’s demands and collecting the revenue that it does. In quarter three Amazon’s sales went up to $43.7 billion, partially due to acquiring Whole Foods, according to the company’s financial results. Amazon also announced that Cyber Monday 2017 was the biggest sales day for the company.

This increase in efficiency has lead to the growth of online retail and Amazon in particular. For 2017, Amazon accounts for 20% of U.S. retail industry growth. Their stock alone went up 57 percent, reflecting the excitement that investors have in automation and Amazon’s foray into artificial intelligence with Amazon Web Services.

With Amazon’s innovation in automation, the company is seeing efficiency in their workforce and supply chain and a highly valued stock, with a price to earnings ratio of nearly 300. At the same time, that means the outlook for labor in retail and at warehouses is dismal.

“I think they are pushing the limits and trying to see what they can do to eliminate their dependence on human labor,” Miller said.

Quartz estimates that employment in retail and at Amazon itself could decrease by 24,000 even though Amazon continues it’s aggressive hiring strategy.

Automation hasn’t gotten to the point of completely replacing humans in warehouses, but rapid technological innovation means that Amazon is one step closer. Miller said that only one out of four unique human characteristics has been successfully modeled in machines, which include cognition, emotion, dexterity and creativity.

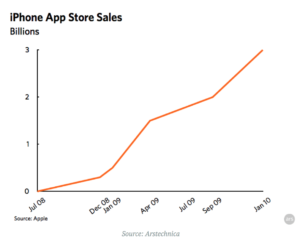

Robots have reached the point of cognition. Google’s artificial reality system, called AlphaGo, beat a master at one of the most complex games in the world. And in 10 years, experts predict that AI will be better at humans than writing a high school essay. Within 74 years, AI could be better than humans at everything.

Machines still struggle with emotion, dexterity and creativity. Once Amazon is able to create a robot that has dexterity analogous to a human grip, there may not be a worker left in a warehouse, apart from engineers.

Yet they still have a lot progress to make. Amazon held a competition in 2015 with aims of developing a “picking” robot that can take items off a shelf and deposit them in a bin. The best robot in a competition with engineers around the world could only pick 10 out of the required 12 items. And it took that robot around twenty minutes to complete its task. For a human it would take a handful of seconds.

Even if humans are faster, workers only spend around one minute per order — picking items, depositing them in bins and assembling and taping boxes. The rest — measuring the amount of tape needed per box, the size of the box and transporting the items around the warehouse — are done exclusively by robots.

The important question, though, is what society and Amazon will do when robots exclude the human element entirely. This increased reliance on automation is different than every major shift in the history of labor.

“The difference this time is that we are beginning to automate cognitive work,” Miller said. “The work that was thought to be purely human.”

Miller said universal basic income, a highly politically sensitive topic, might be a solution.

Universal basic income essentially pays people for being alive. Money would be handed out by the government at a recurring time to everyone, independent of their age, employment status and a whole host of other variables. The only issue is figuring out to pay for it.

A pilot program in Finland is paying 2,000 people an income of 590€ a month for two years since the program started in Jan. 2017. The idea is to find out if people will abuse the money or use it to start a business or find another job that a robot potentially couldn’t do. Hawaii also passed a resolution in June to request that their state government “convene a basic economic security working group” to determine the feasibility of UBI.

“The data that’s been collected from pilot programs tends to show positive effects,” Miller said. “In fact, some people are more likely to work more because they avoid the traumas of just struggling to eat and have a roof over their heads.”

Whether or not UBI is implemented in the U.S., when companies like Amazon make the transition over to full automation in their warehouses, families will have more time to engage in intrinsically valuable work. Miller said that looks like caring for older family members and putting children through school.

Amazon’s response by their employees and spokespeople to the threat of labor displacement has been mild and even positive in the media, when the potential effects of automation are negative. Another more positive economic view could justify Amazon’s happy-go-lucky response.

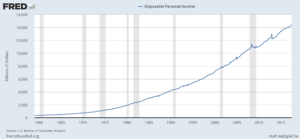

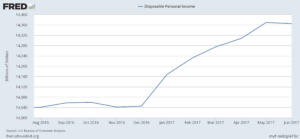

One, automation can induce more demand, which may make it necessary for Amazon, in this example, to hire more workers. It will increase the company revenue, leading to higher pay, and thus more demand for goods as workers will have more of a disposable income.

Two, other jobs will be created in the absence of the warehouse type work at Amazon distribution centers. Every ten year period since 1929 has seen increases in productivity and employment. Still, the future is uncertain.

“The concern has always been with these waves of automation is that ok this time it will be different, this time the new jobs won’t appear,” Miller said. “Because while the automation is taking place there isn’t a clear roadmap to where the new jobs will be.”

Finally, the working population in the U.S. and many other countries is on the decline. Employment, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, will have an average growth of about 0.3 percent per year for the next 50 years. So it may be necessary for those robots to step in where labor shortages, not only in Amazon, but in other companies, will affect their production.

Other competitors to Amazon are making use of robots too. Quiet Logistics runs fulfillment centers for companies who compete with Amazon, and they have recently launched their own robots, which function similar to Amazon’s machines. They are predicting that warehouse productivity will shoot up 800 percent.

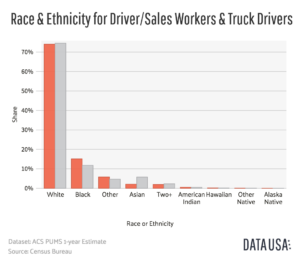

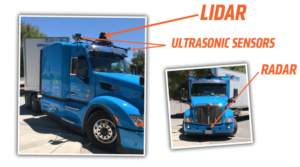

Amazon is bringing automation beyond just the warehouses and distribution centers. Select Amazon Prime members in the U.K. are getting their products delivered to them by drones, which would completely cut out the delivery truck driver. Automation of long-haul and delivery truck drivers threatens nearly 2 million people according to the White House under the Obama administration.

The Amazon Key system is another way the company is automating the way that products arrive at your door. It allows delivery men to drop off packages inside your house as opposed to the porch. The system requires Amazon Prime Members to shell out around $200 for a camera, new lock and installation. With those three items, a person can monitor the delivery and the person delivering the package can unlock the house with a swipe on his or her phone.

Drones and access into a customer’s home are just two ways Amazon is trying to control all aspects of the distribution of the products that they sell in addition to the retail experience itself. Implementing Amazon Alexa into BMW and Mini cars and making it easy and inexpensive to install in homes, they are making the online shopping experience more personal. Though the vast expanse of the U.S. will make it harder for Amazon to control that delivery experience everywhere, Miller said.

Now, humans and robots are working with each other on a scale never before seen in human history, though that symbiosis will not likely last for long due to improvements in robotic technology and artificial intelligence. Robots will soon be able to outperform humans in the foodservice industry, writing and driving, all of which constitute a large portion of the American workforce. In higher-up company roles, robots will increase productivity and do part of the job of leaders, managers and engineers.

Amazon on its own is speeding that process along as it continues to make strides in automation by replicating the work that their employees already do. Humans will therefore be replaced in many industries soon. This fourth industrial revolution presents policy and economic solutions from UBI to government regulation. How society and governments respond to this ongoing threat to labor will shape what the future might look like when many people are out of work.

“This is going to be a massive social challenge. There will be fewer and fewer jobs that a robot cannot do better [than a human],” said Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, at the World Government Summit. “These are not things that I wish will happen. These are simply things that I think probably will happen.”