By Sarah Montgomery

Forever 21. Payless. Sears. Toys R Us. These are a few of the many titans who have declared bankruptcy in the wake of the “retail apocalypse.” As retail migrates from brick-and-mortar stores to the internet, it is essential to acknowledge the fundamentally negative impact this will have on America’s future.

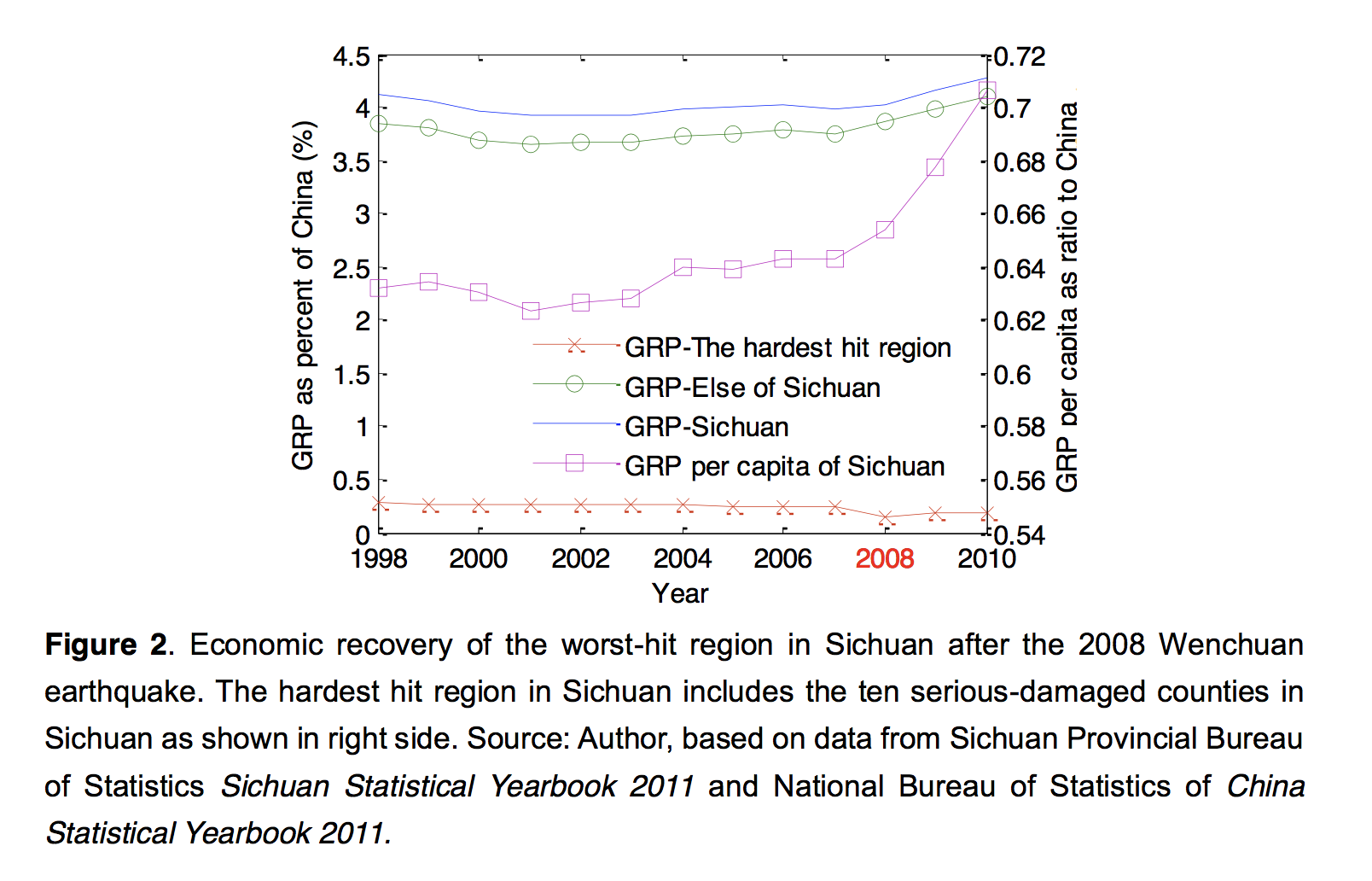

By 2022, analysts estimate that one out of every four American malls could be wiped out. That contradicts the narrative about the country’s economy— the economy is growing, unemployment is low, and consumers are confident. There are many reasons why traditional American retail is in a death spiral; the primary one being the rising popularity of online commerce, particularly brands dubbed as “e-tailers”. The losses of the brick and mortar market have been offset thus far by the success of online commerce— however, the honeymoon will not last forever.

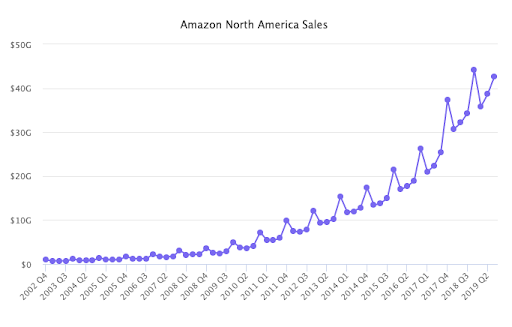

Year-to-date, Amazon has reported $117.1 billion in North America sales— and we have not even hit the busy holiday season yet— and has enjoyed an average 26% annual growth rate since 2016. For context, Target reported $75.36 billion in North American revenue for all of 2018 and an average 1.85% annual growth rate since 2016. E-commerce is outpacing traditional retail like a cheetah racing a housecat.

Without a doubt, the popularity of online stores is eating at retail’s success. Gabriel Kahn, a journalism professor at USC, likens the situation to bringing a knife to a gunfight. Without the overhead costs of brick-and-mortar stores, online retailers can compete in ways that traditional retailers simply cannot. With the offers of next-day delivery, online price comparison tools, customer ratings, a larger inventory, less of the friction inherent in person-to-person interaction, and more, all accessible from the comfort of the buyers’ couch, there is no way physical retailers stand a chance. Though the e-tailer boom has meant increased convenience for the consumer, the cons certainly outweigh the pros. Convenience cannot be our god in this economy.

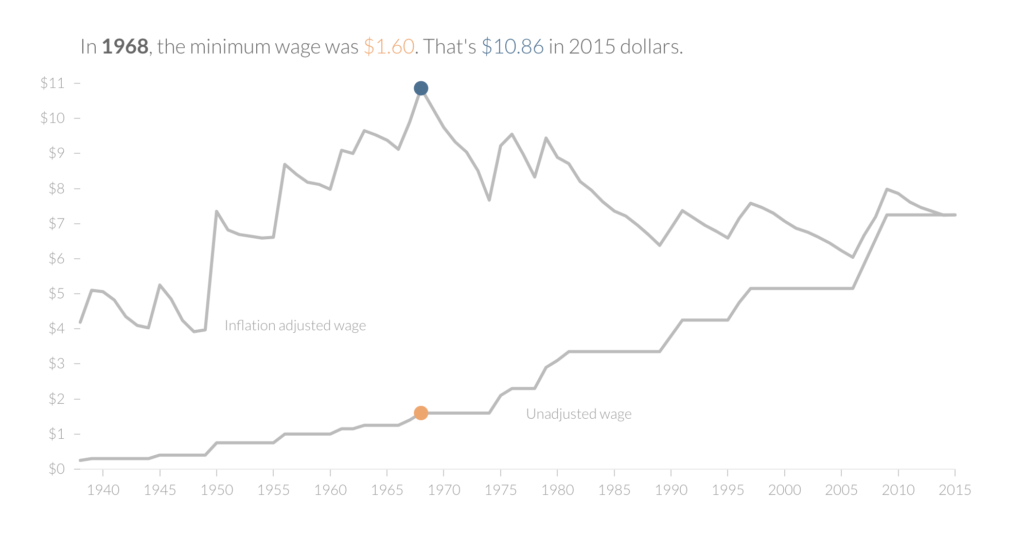

According to the Pew Research Center, America’s middle class is falling behind financially after spending four decades as the nation’s economic majority. According to the study, “the nation’s aggregate household income has substantially shifted from middle-income to upper-income households;” the income held by the American middle earners has shrunk from 61% to 50%. As people work for less money and work more hours to try and overcome income shortfalls, the Average Joe and Average Jane have less time and money to spend in stores.

Those who have disposable income are certainly not spending it on food court meals and trinkets from Macy’s, ultimately hurting the businesses that occupy the average mall. The malls that are surviving, like The Grove, cater to a more high-end, luxury market that is increasingly inaccessible to the middle class. The mall where grandmas and goths could all find something they wanted, where the rich and poor could spend time and not feel out of place, where teenagers got their first jobs, where families went to get some Sbarro’s before a showing at the AMC, where millions of Americans ambled away hours of free time— this modern suburban shopping mall will become a nostalgic memory.

“Advances in technology, such as self-service checkout stands in retail stores and increasing online sales, will reduce the need for cashiers,” says the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

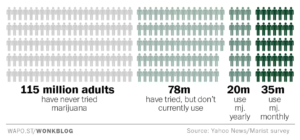

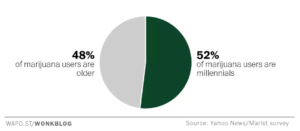

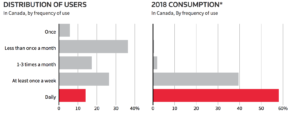

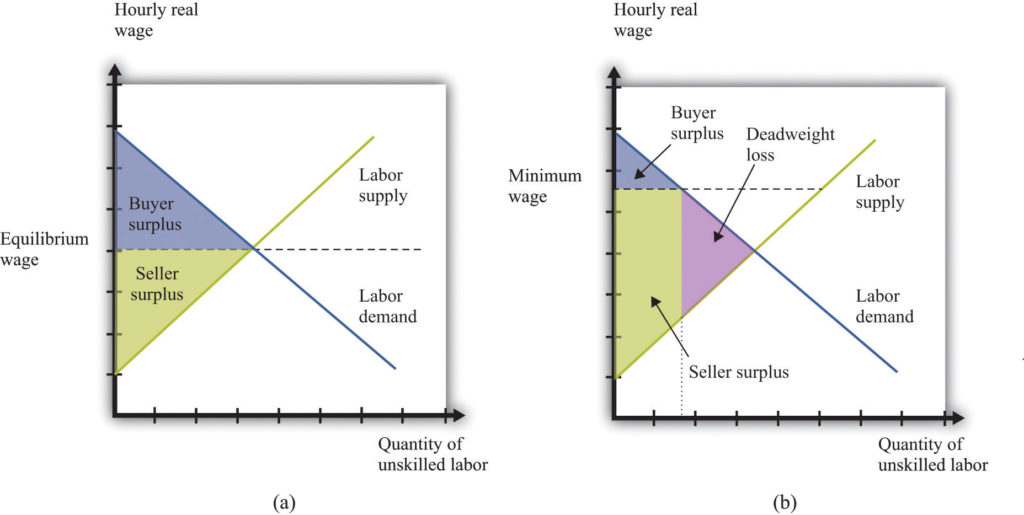

The problem of retailers dying off is exacerbating the financial plight of the working class. Back in May 2015, retail salespersons and cashiers were the occupations with the highest employment. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that cashier jobs will have a negative employment change of -138,700 people (4% decline), whereas retail sales workers will likely experience a negative change of -105,200 jobs (2% decline). Stragglers may be sucked into markets related to online commerce, like truck driving or warehouse jobs (which have appalling work conditions), but those jobs are at risk of being automated in the near future. We will lose jobs essential to the wellbeing of the middle class. As reported by NPR’s “Planet Money,” truck driving, retails sales clerks, cashiers, and customer service representatives— all currently impacted by the retail apocalypse— are popular jobs for middle- to lower-income brackets.

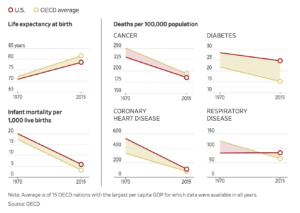

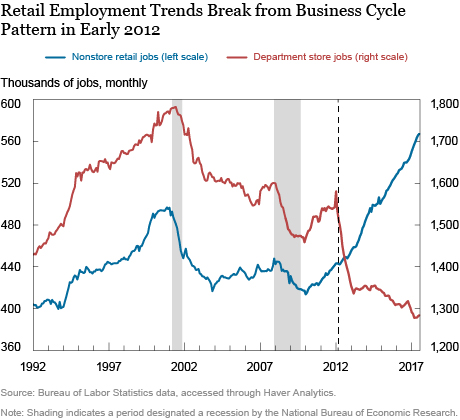

For now, the loss of retail jobs has been offset by the increase in other job sectors, like the aforementioned warehousing, giving off the illusion of a bustling economy. That being said, it is important to keep in mind that those new jobs are not likely to be placed in the same suburbias where those malls once were. Department stores have an incentive to spread their products, and thus staff, throughout the country; e-tailers do not have such an incentive. The regions losing jobs are not seeing that problem mitigated by new jobs. Moreover, as posited by economy researchers Jason Bram and Nicole Gorton, non-retail jobs may demand a more sophisticated skill set than department stores; they liken salary as a proxy to skillset, noting that the average wage for non-store workers exceeded $59,000, whereas the average salary for department store jobs hovers at just $20,500. As obtaining a college education gets more and more expensive, there seems to be no way out for the middle class. Without access to low-skilled jobs, and without the education to secure skilled work, the middle class will be hollowed out.

But wait: it gets worse. With less money being earned by its citizens, local governments will indubitably suffer. Sales tax and income tax comprise a large part of any city’s government. As malls and the correlated jobs die, so do two major sources of revenue that are nearly impossible to recuperate by other methods. Across the nation, sales tax comprises nearly 33% of state governments’ revenue and about 12% of the local government’s revenue. As malls and retail stores either collapse or flee to more prosperous regions, those localities also see a loss in commercial property taxes.

I spoke with Jason Kruckeberg, the Assistant City Manager/ Development Services Director of Arcadia, Calif. The city has a thriving Westfield mall thanks to how deftly it serves the large Asian demographic. He says the city reaps many benefits from the mall, considering the sales tax, employment tax, property tax, introduction of money into the local economy, tourism, name-recognition and community events that the Westfield Santa Anita promotes. Just looking at sales tax alone, for the 2017-2018 fiscal year of Arcadia, sales taxes generated $10,670,332 dollars whereas next-door neighbor Monrovia collected $2,404,000 in sales tax that same fiscal year.

Facing reduced tax revenue, governments can provide less social services when relief is needed most, while concurrently raising taxes (further aggravating the problem). Some people, like Alana Semuels of The Atlantic, argue that a viable solution to this problem could be the requiring of online retailers to collect sales tax and redistribute it to the states. Though an interesting solution, it would require an act of Congress, a lengthy and difficult process. Things will get worse before they get better.

Any competent economist knows that behavior and the economy are closely linked. Displaced workers, shrinking tax bases, widening economic inequality, and reduced money flow is a recipe for disaster. With less consumer confidence, especially in the consumer-driven American economy, the repercussions could be severe. Money is the blood that circulates through the economy, keeping the system alive; without that flowing, the consequences will be grave— economically, politically, and culturally.

Stacey Li

Stacey Li

Source:

Source: