The RASIE Act, immigration reform proposed by U.S. Senator for Arkansas, Tom Cotton, and back by President Donald Trump, was introduced to diminish the number of low-skilled, unskilled and non-citizen immigrants taking American jobs. The sectors that have highest number of foreign workers are seen in agriculture, construction and services. It is no coincidence that low- to medium-skilled jobs are dominated by immigrants. The high number of foreign workers in these sectors is not due to non-citizens taking Americans’ jobs. Rather, it is because of the work conditions.

“Low-skilled jobs are low status, pay low wages, and are physically challenging,” Dean and Professor of Public Interest Law and Chicano/o Studies at the University of California, Davis, Kevin Johnson said. “Employers often say that they cannot get U.S. citizens to fill these kinds of jobs.”

The main aim of the RAISE ACT is to protect American taxpayer workers, taxpayers, and the economy. However, the repercussions of this reform could instead worsen the U.S. economy. If enacted, a rise in low- to medium-skilled job openings will occur. This will put a strain on businesses to operate with fewer employees. An attempt to operate with fewer employees working longer hours or increasing the wage to attract workers will in turn increase the cost of goods and services. This could potentially send many companies out of business. If the government decides to offer incentives to encourage Americans to take low- to medium-skilled jobs, it will be out of their pocket, or the Americans taxpayers’ pockets. Neither is desirable. Nor is this reform.

The proposed merit-based immigration system will prioritize immigrants based purely on the skills and knowledge they bring to the U.S. The proposed merit-based immigration proposal is modeled on the current Canadian and Australian systems. The reason behind modeling these two countries is that Canada and Australia attract highly skilled workers and see healthy growth, productivity and income per capita.

The skills-based system rewards applicants points based on individual merit. The system rewards points in areas such as higher education, English language ability, high paying jobs, and past achievements. The various ways that migration and population growth can be linked to Canada and Australia’s productivity and income per capita growth include, supply of labor; capital, investment; government expenditure on services and taxation; competition; natural resources, land and environmental externalities; and international trade.

The RAISE act doesn’t take into consideration the aging population. The U.S. population is aging rapidly as baby boomers enter old age and retirement. The Population Reference Bureau reported the number of Americans aged 65 years and older is projected to more than double from 46 million today, to over 98 million by 2060. The 65 years and older group share of the total population will rise to nearly 24 percent from 15 percent. An aging population has a direct impact on the labor force. This will result in a dependence on immigrants to replace current workers and fill new jobs.

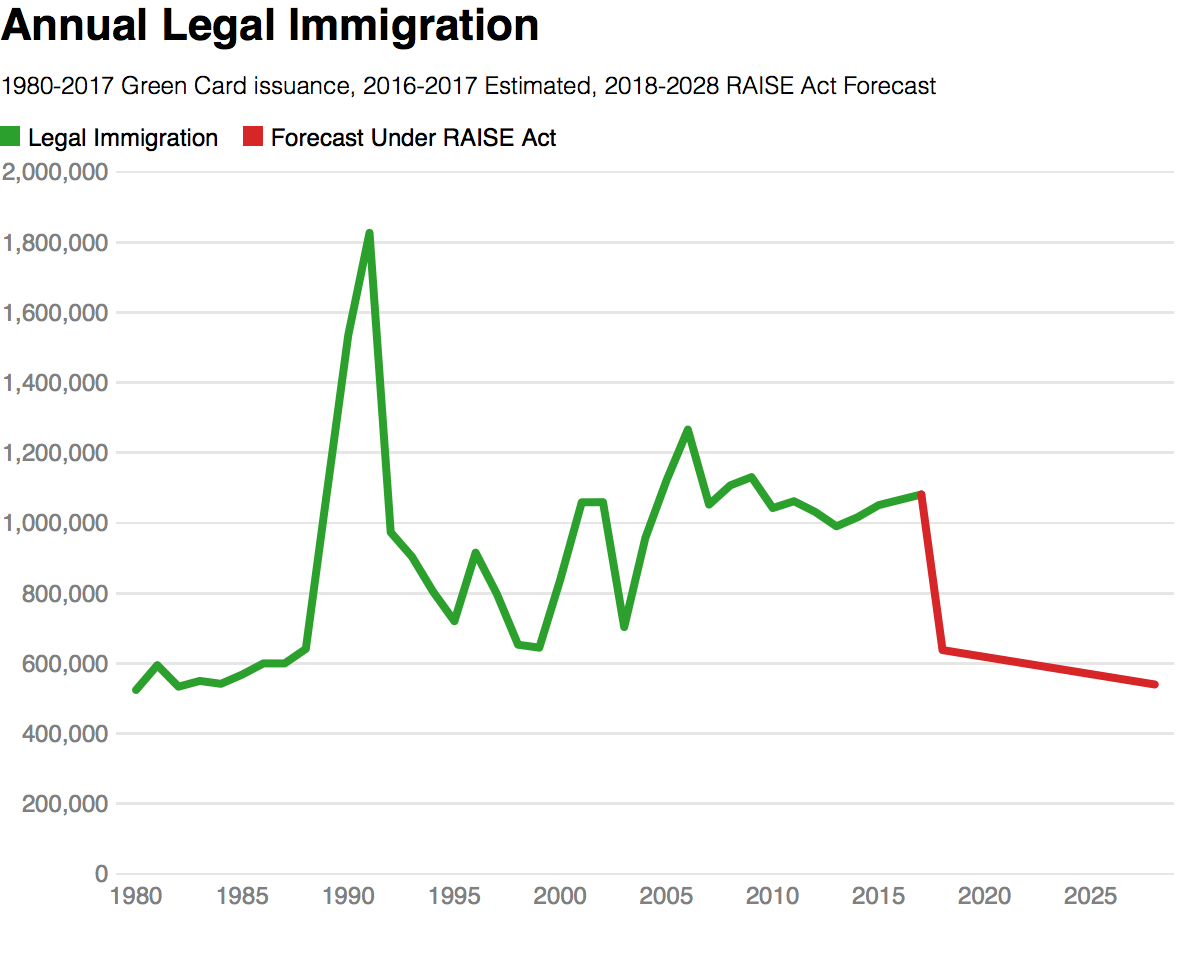

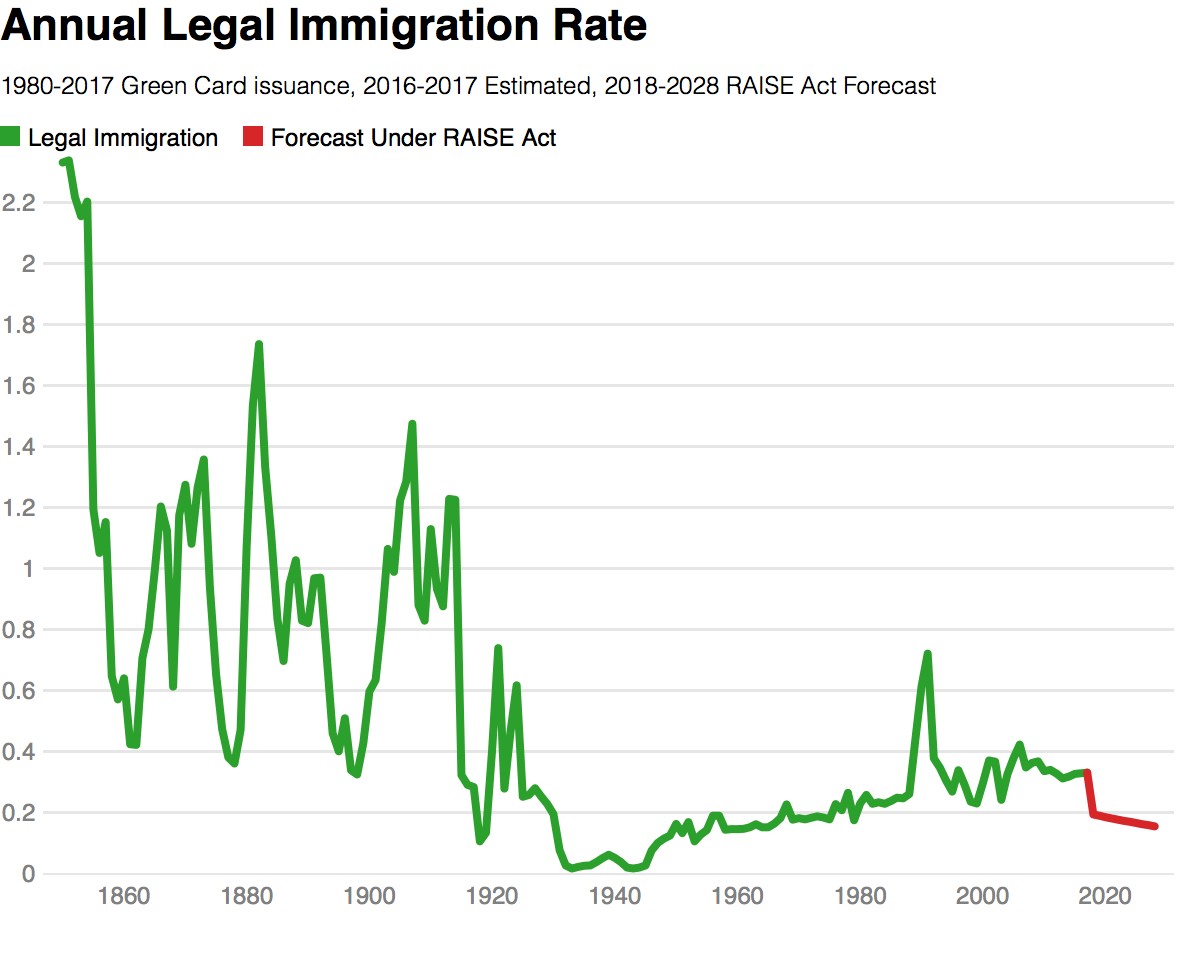

In fact, The Raise Act would have the opposite desired effect of what the Trump administration propose the legislation will do, and sharply reduce legal immigration, and increase illegal immigration. The graphs below show legal immigration as a percentage of population since 1850.

Both graphs demonstrate The RAISE Act would be a significant reeducation in total legal immigration, and it would have no direct impact on illegal immigration. It is almost certain that more restricted access to legal immigration for family members of current immigrants would result in higher levels of illegal immigrations by those family members.

Deputy Dean and Director of the Public Law and Policy Research Unit at Adelaide Law School at the University of Adelaide in Australia, Alexander Reilly, said increasing skilled migration at the expense of family migration can impact on the desires for family reunion of existing U.S. citizens.

“In Australia, parent migration is very difficult,” Reilly said. “It may be that partner and child migration, which is currently considered a matter of right here, will have quotas or waiting lists imposed.”

A problem Reilly sees in Australia with independent skilled migration is that migrants find it hard to get jobs in their area of expertise and end up unemployed.

“Skilled migrants’ success is better if they have family support, so merit-based migration definitely needs a strong family component.”

Johnson agrees, believing a merit-based immigration system that halves the number of legal immigrants entering the country will unintentionally increase the number of undocumented immigrants.

“The goal of the U.S. government is to reduce legal immigration from one million a year to 500,000 a year, and this reduction will be seen in family immigrant visas,” Johnson said. “With the current limits on legal immigration, this has bought in roughly 11 million undocumented immigrants to the U.S.”

“Making legal immigration even more restrictive will increase the likelihood that those who want to immigrate lawfully will resort to doing so illegally.”

In 2015 to 2016, Australia accepted 189,770 permanent migrants through its skilled and family immigration streams, and settled 18,000 refugees and humanitarian migrants. Sixty-seven percent of migrants came through the skilled stream, and 30.8 percent through the family stream. These numbers add almost one percent to the Australian population each year, a much larger proportion than the U.S. admits through its migration program.

Immigration is the largest contributor to population growth in Canada since the early 2000s. Canada’s permanent immigration program is divided into three main streams: economic, family and humanitarian. In 2015 to 2016, Canada admitted 271,845 permanent immigrants. Of this number, the economic stream accounted for 60 percent of migrants, family made up 24 percent, and the remaining were humanitarian migrants. These proportions have remained fairly stable over the past 15 years.

In Australia, there are two pathways for skilled migration. The first, general skilled migration, requires applicants’ occupations to appear on a skilled occupations list. Most of these occupations are in professional areas such as medicine, engineering, or trades. The list is updated regularly based on an assessment of Australia’s economic needs at the time. The second pathway is for skilled migrants with an employer sponsor. This pathway is open to migrants with a wider range of skills. Employers must demonstrate they have a skilled position available and there are no Australians willing or able to take up the position.

A merit-based immigration system will transform the U.S. immigration system from primarily family-based to employment-based. Under the U.S.’s current system, most employment-based immigrants are highly skilled, but make up only 14 percent of those who receive green cards. Under the RAISE Act, employment-based immigrants would make up the majority of those who receive green cards.

In the proposed points system for the U.S., applicants would earn points for meeting criteria to do with age (preference for persons between ages 26 and 30) and having a degree. Extra points would be awarded for degrees earned in the U.S. and in a STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) field. Nobel Prize winners, professional athletes and English language speakers would also receive extra points.

Johnson said that while the Australia and Canada case studies were worth reviewing, the U.S. has its own history and political, social and economic forces that contribute to immigration pressures and flows that may not exist in Canada or Australia.

“Australia and Canada don’t operate in the same context as the U.S., so those main factors must be considered in any reform of U.S. immigration law,” Johnson said.

When asked if the RAISE Act will reduce poverty, increase wages and save taxpayers millions of dollars, as stated by President Trump, Johnson replied, “There is no empirical evidence to support this claim.”

References

Camarota, S. A. (2015, September 10). Welfare Use by Immigrant and Native Households: An Analysis of Medicaid, Cash, Food, and Housing Programs (Report.). Center for Immigration Studies. Retrieved October 4, 2017, from Center for Immigration Studies website: https://cis.org/Report/Welfare-Use-Immigrant-and-Native-Households

Infographic: Annual average growth rate, natural increase and migratory increase per intercensal period, Canada, 1851 to 2056. (2017, March 30). Government of Canada. Retrieved October 04, 2017, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/170208/g-a001-eng.htm

Mather, M. (2016, January). Fact Sheet: Aging in the United States. Population Reference Bureau. Retrieved October 04, 2017, from http://www.prb.org/Publications/Media-Guides/2016/aging-unitedstates-fact-sheet.aspx

Reilly, A., Paquet, M., & Johnson, K. (2017, September 17). RAISE Act: Global panel of scholars explains ‘merit-based’ immigration. The Conversation. Retrieved October 04, 2017, from http://theconversation.com/raise-act-global-panel-of-scholars-explains-merit-based-immigration-82062

Salerian, J. (2006, May 17). Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth (Report.). Retrieved October 4, 2017, from the Australian Government, Productivity Commission website: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/migration-population/report

Singer, A. (2016, August 02). Immigrant Workers in the U.S. Labor Force. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved October 04, 2017, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/immigrant-workers-in-the-u-s-labor-force/

Stone, L. (2017, August 3). Everything You Need To Know About The RAISE Act Without Reading It. The Federalist. Retrieved October 4, 2017, from http://thefederalist.com/2017/08/03/everything-need-know-raise-act-without-reading/

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. (2017, August 2). President Donald J. Trump Backs RAISE Act [Press release]. Retrieved October 4, 2017, from President Donald J. Trump Backs RAISE Act

U.S. Congress, Senate – Judiciary. (2017, February 13). Congress.gov (T. Cotton Sen., Author) [Cong. S.354 from 115th Cong., 1st sess.]. Retrieved October 4, 2017, from https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/354/text