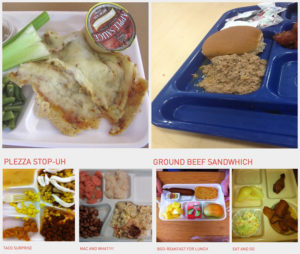

A handful of tater-tots coupled with pizza the size of your palm (with two whole pepperoni slices!) on top of a disposable styrofoam tray was considered a really good day at the cafeteria. On other days, students were in for more of a surprise: a mystery meat accompanied by chocolate or strawberry milk would be received differently by everyone. Very few are satisfied with the lunches but it is too late to revamp the American public school lunch system. This is not simply an issue to bad food, but really a problem of money. The health of this generation is at stake, but corporations are not interested in the health of kids, but only profits.

Regardless of the menu, school lunches in American public schools often elicit an image of a soggy, plastic-y, hot (or sometimes cold) mess. Part of this is due to the vague definition of vegetables from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Our nation’s nutrition standards that guide public school lunches describe potatoes as a vegetable, and, by association, french fries are classified as vegetables. The tomato paste in the pizza, pickle relish, and ketchup all qualify as vegetables in the confines of American lunchrooms and pass as “healthy” food.

Why are the health guidelines for school lunches so confusing? And what does that have to do with the bad food? In 1947, Congress passed the National School Lunch Act, which aimed to ensure all kids in America that could not afford lunches at school would still be fed, even if the government had to subsidize their meals. Even with the suspicious standards for food, the intentions of the government were good—they wanted to keep kids from going hungry at school. But today, the American public school lunch system tells a revealing story of Federal budgeting and how policy actually plays out from the Congressional floor to elementary school lunchrooms and beyond.

Budget Food

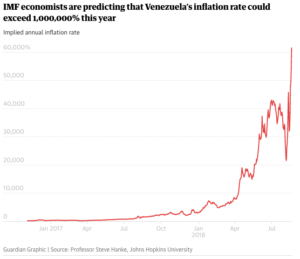

1935 was the first year Congress set aside money in the school lunch program. The government initially used the surplus food from farmers like dairy, wheat, and pork to make these meals. As more children started eating government-funded lunches, the budget steadily increased because the lunch programs needed even larger quantities of food, no longer utilizing surplus food, but created a demand. But in the 1980s, the Reagan administration faced the difficult problem of cutting the Congressional budget. From the overall $615 billion of the 1981 fiscal year, the school lunch program became the victim of the budget cut. President Reagan reallocated $1 billion from the lunch subsidies, reducing the U.S. government spending to a reported $3.6 billion overall for school lunches. This 24 percent decrease in lunch funding led to creative ideas from the Reagan Administration to pinch pennies. Controversially, ketchup was presented as a vegetable during this time, and these bold classifications of vegetables have continued. Even today, within Congress and the administration, there is a constant struggle to keep the budget as small as possible because the spending on child nutrition programs grows at exponential rates. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the spending more than doubled since the 90s and is projected to rise continuously in the future. Despite the increase in budget, nutritional programs often grow at similar or faster rates, resulting in a shortage of money.

The money to provide these services and food gets tighter every year, so do the health standards. The demand for low- and no-fat foods has surged since the 90s. Today, the meals schools serve have a calories limit ranging from 650 to 850, depending on the age range of the children. Not only that, the minimum servings of fruits and vegetables doubled, “dark green and orange vegetables” now replace the previous potatoes and tomato paste as vegetables, offering a wider variety of real vegetables. Meals are now served with less sodium, less saturated fats, and a reduced amount of added sugars. No more sugary drinks or unhealthy snacks… the list goes on.

The stricter health guidelines are largely due to two things. The first is the Free and Reduced Lunch program, which derived from the initiative to feed every child in our schools. The National School Lunch Act guarantees lunch for everyone. These lunches play an important role for many children; President Obama once noted that, for many children, school lunches are “their most nutritious meal—sometimes their only meal—of the day.” Last year, a whopping 4.9 billion lunches were served. If we break this number down to a daily basis, American public schools served 30 million lunches in one day: 20 million of which are free, 2 million were at a reduced rate, and 8 million were paid in their full price. If over two-thirds of lunches served receive their food at a reduced or free price, it’s a good indicator that many children are indeed dependent on these school provided lunches.

The other reason the USDA began to enforce tighter health guidelines was due to the obesity epidemic the media extensively covered in the early 2000s. From the University of Michigan, Dr. Kim A. Eagle’s research study identified school lunches as another risk for childhood obesity. One of most jarring statistics stated that “those who regularly had the school lunch were 29 percent more likely to be obese than those who brought lunch from home.” Eagle attributes this to the fact that school lunches rely on high-energy, low-nutrient-value food, which was usually centered around corn and potatoes, because of their lower costs. The First Lady Michelle Obama created the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act, an initiative to combat obesity, promoting not only exercise, but also pushed for stricter health guidelines for students.

The constant shaving of the Federal budget alongside strict health standards had left America with very few options. Processed foods were on a rise in response to this situation. The opportunity to turn Federal dollars into a lucrative business propelled companies such as Tyson and PepsiCo to capitalize on this opportunity. These companies began lobbying efforts to ensure their products were used in lunchrooms.

In these conversations where the decision making for school lunches take place, there are two other major players: the SNA or School Nutrition Association and the National School Boards Association who represent the interests of students and as advocates of schools, and organizations such as the Food Research and Action Center and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities who examine the nutritional value of food.

Though SNA is supposed to advocate on behalf of schools, the School Nutrition Association’s website shows that lobbying groups such as Tyson and Pepsico are listed as partners. While the processed foods are not a good thing, it’s all the schools can realistically afford. Such high health standards with a significantly low budget from the government is a tall order to fulfill.

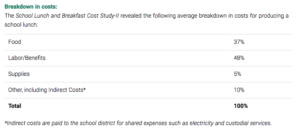

When asked about the amount of processed foods in school lunches, the SNA stated, “While many school are working to increase the amount of freshly prepared and scratch-made menus items, those with limited equipment and labor resources rely on healthy pre-prepared foods to ensure students receive balanced meals each day.” Even if there is enough money to assemble all the ingredients for healthy, unprocessed meals, there is not enough to employ kitchens to cook and serve children.

A myriad of factors are all complex layers to the problem of American public school lunches: the shrinking Congressional budget, the high reliance on free and reduced lunch, the intricate health standards, and lobbying groups of processed foods. The system has ballooned so much and fallen too deep to fix.

SOURCES:

https://www.cnbc.com/video/2018/11/14/heres-who-gets-rich-from-school-lunch.html

https://www.cnbc.com/2018/11/14/how-big-brands-like-tyson-and-pepsico-profit-from-school-lunches.html

https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/child-nutrition-programs/national-school-lunch-program.aspx

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/50737https://firstfocus.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Nutrition-Budget-Fact-Sheet-FY18-PDF1.pdf

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/08/how-to-scale-up-healthy-eating-in-schools/

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/usbudget/bus_1981.pdf

https://schoolnutrition.org/AboutSchoolMeals/SchoolMealTrendsStats/#1

https://www.fns.usda.gov/nslp/history_5

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/new-nutrition-standards-for-school-lunches/