By Sarah Montgomery

Taylor Swift’s music has changed in more ways than one. The country-turned-pop singer’s catalog of music recently changed hands, from Scott Borchetta to Scooter Braun.

Photo courtesy Taylor Swift’s Instagram account

Borchetta sold Big Machine Records to Braun, a manager for many big-name artists , for $330 million dollars. As part of that deal, Braun acquired the music rights to everything the label owns. Five of Swift’s six albums are now his property.

Swift was offered the opportunity to buy back her masters (music industry jargon for the first recording of any song)—with a major catch. Under Big Machine, she would have been able to buy back each album with a new one in exchange. In essence, she would have had to sell away her future to buy back her past. She refused, leaving her old art with Big Machine, and moved to Republic Records in 2018.

Swift was one of the biggest artists under Big Machine, which houses lesser-known stars like Thomas Rhett and Lady Antebellum. Allegedly, Borchetta had been looking for a buyer for years. If he had let Swift buy back her music, he would not have gotten nearly as much money as he did in his deal with Braun.

In most cases, this would not be newsworthy. Many artists don’t have ownership over their own work; it is an accepted reality in the music industry.

The big deal is that Swift vehemently hates Braun. She has called him a bully, going so far as to say “my musical legacy is about to lie in the hands of someone who tried to dismantle it.” She specifically cites an instance in which he and two of his clients, Justin Bieber and Kanye West (with whom she has legendary drama), got on a FaceTime call and posted a photo of it with a caption that taunted her. She also points out that West used a lookalike of her naked body in a music video, which she amounts to finding Braun complicit in revenge porn.

Photo courtesy Taylor Swift’s Tumblr Account

Swift does not have many options to better her situation. She plans to re-record the old songs, which she is contractually allowed to do in November 2020. This will devalue her entire catalog, as there will be two copies of one product. Alternatively, according to the 1976 Copyright Revision Act, artists can reclaim ownership after 35 years.

The most she can do is pressure Braun to let her buy back her masters, which is why her social media campaign against him may prove useful. That being said, Swift is worth about $320 million. It’s possible that even if she had the opportunity to buy back her masters, she would not be able to afford it.

Swift is already feeling the repercussion of a wrathful custodian. Financially, it is in Braun’s best interest to license Swift’s music. But he, a man worth $400 million, could theoretically shoulder a few losses to punish her for lashing out.

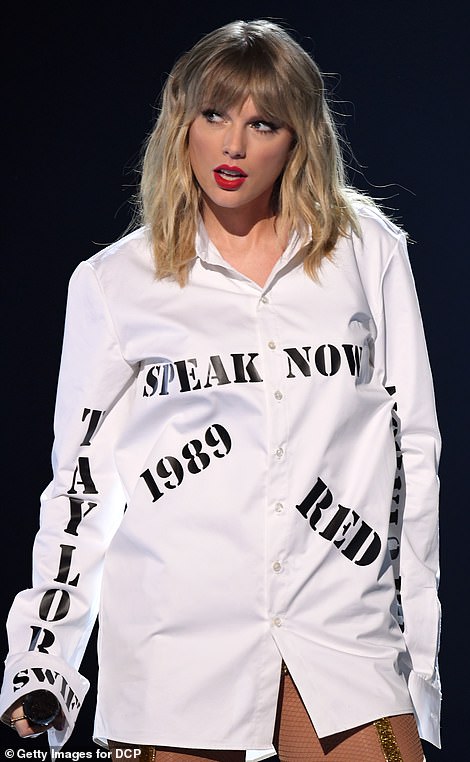

Photo courtesy Getty Images

Her team announced that the record label is not letting her use her old music or performance footage for a few major projects, notably a Netflix documentary and the Alibaba “Double Eleven” event she performed at. She just barely got permission to use her music for a performance at the American Music Awards. Considering the majority of money artists make comes from touring and concert sales, this next year could very well be a financial dry spell for Swift.

Record labels hold an unbelievable amount of power in the music industry. Whoever owns the masters will always control and benefit from any use or licensing of those songs. For this reason, many artists are going independent these days or are strictly negotiating ownership rights. With the rising popularity of direct-to-consumer distribution platforms, such as Sound Cloud and Youtube, being independent has never been easier.

On the other hand, there are a lot of perks for signing with a label—a massive advance (read: money), access to a strong industry network and other benefits that vary by contract. The most important thing for many artists is that labels will often handle the entire business side, from marketing to brand management. So labels will take a gamble, financially backing and professionally supporting you now—at the cost of owning your music and the majority of your future earnings.

Photo courtesy One Love Manchester

Because contracts are usually very private, the financial arrangement between Big Machine and Swift is not entirely clear. Let’s imagine that, through subscription costs or advertising revenue, consumers are ultimately paying Spotify $1.00 per stream to listen to “You Belong With Me.” Typically, about 70 cents of that dollar goes to the rights holder, in this case being Big Machine. If the label were to pay the artist 15% of their share, that would amount to just 10.5 cents to Swift. And remember, that’s just an estimation; labels have total discretion of how much they will pay artists.

Courtney E. Smith, a writer for Refinery29, notes that labels tend to have shady accounting practices, so trust is an essential aspect of any artist-record label relationship. Braun may drastically reduce her payout from the company for her work or maybe even not pay her at all. As it is now, Swift already claims that the label owes her $8 million in unpaid royalties.

Swift, who signed with Big Machine at age 15, is using this all as a cautionary tale to up-and-coming artists. “Hopefully, young artists or kids with musical dreams will read this and learn about how to better protect themselves in negotiation,” Swift writes. “You deserve to own the art you make.”