In September 2017, WeWork became the sixth most valuable startup in the world. The co-working company takes on long-term leases for raw office space and builds out the interior into trendy, millennial friendly spaces that are then subleased to Fortune 500 companies and startups alike, one conference room or desk at a time.

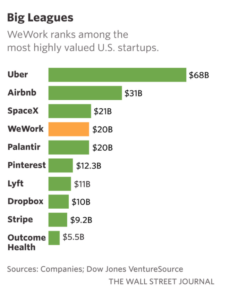

To provide a sense of WeWork’s fast-spreading dominance, the startup has dazzled tech investors by portraying itself as a Silicon Valley-style company that serves as a “physical social network” for millennials. It has raised over $8 billion to date, accruing over $4.4 billion through the Japanese tech giant SoftBank’s Vision Fund in 2017 alone. Additionally, it was valued at $20 billion this year, which is the largest valuation in New York City and the third biggest startup valuation in the United States after Uber, Airbnb and SpaceX.

The impressive valuation of a startup – which coincidentally encourages the startup lifestyle – is worth more than Twitter ($12.96 billion), Box ($2.44 billion), and Blue Apron ($1.54 billion) combined, Business Insider reported. Yet, industry experts, professors, and the general public has been left scratching their heads whether the co-working giant can justify its grandiose appraisal. With a $20 billion valuation that is eight times that of a traditional leasing company with a similar business model warrants a major question: is WeWork overvalued?

First, let’s take a look at how WeWork came to be the highly talked about startup it is today.

CEO Adam Neumann was born in Isreal and moved to the United States in 2001 after serving as a naval officer in the Israeli military. “Before I started WeWork, I owned a baby clothing company based in Dumbo, Brooklyn,” he said in an interview with Business Insider. The company, called Krawlers, sold clothes fit with padded knees for crawling babies. “We were working in the same building as my co-founder Miguel McKelvey, a lead architect at a small firm. At the time, I was misguided and putting my energy into all the wrong places” he said.

McKelvey and Neumann noticed that the building they both worked in was partially vacant. With the combination of their individual architectural and entrepreneurial expertise, they came up with the idea to open a co-working space for other entrepreneurs. Although it took tremendous convincing of their landlord, McKelvey and Neumann opened the first floor of a co-working startup called Green Desk in 2008 – the early incarnation of the company that would contrive WeWork. The “green” in the name was inspired by the company’s focus on sustainable co-working spaces featuring recycled furniture and electricity that came from wind power.

Despite Green Desks near-instant success, Neumann and McKelvey eventually sold the business to their landlord, Joshua Guttman. The WeWork co-founders recognized the importance of being green, but felt the focus of their business should revolve around community. The two founders knew they were onto something and possessed a strong concept. After pocketing “a few million” from the Green Desk sale, the two men founded and launched WeWork.

WeWork, in its current iteration, opened its doors to New York City entrepreneurs in April 2011 and has since expanded to cities across the country and worldwide.

At WeWork offices, options include a single desk in an open floorplan, dedicated private offices with doors, and full floors for more established companies. Amazon.com Inc. and International Business Machines Corp. have both taken advantage of the entire-floor leasing option. Common spaces feature comfortable couches, fun and interactive amenities like foosball tables and beer kegs to encourage meetings and socializing, and various office events take place frequently.

Moving on, we must raise another question: what industry is WeWork in exactly?

Neumann has blatantly denounced defining WeWork as a real-estate company or tech company. The “We Generation,” as he calls it, strives to encourage sharing and collaboration rather than isolated office places. Neumann instructed the WeWork Public Relations representatives to push back against any characterization in the media of WeWork as a myopically defined real-estate company and instead encouraged the description of WeWork as a “lifestyle” or “community-focused” company.

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Artie Minson, WeWork’s president and chief financial officer said, “we frankly are our own category. We use real estate and services to empower our community.” Minson supported the company’s sky-high valuation, stating it made sense because investors are looking to WeWork’s plans for growth and confident in the acquisition of millions of members in the future.

The WeWork client is “coming to (the company) for energy, for culture” Neuman stated at an event this summer, aiming to breakaway from a pigeonholed industry classification. The Wall Street Journal reported that Neumann and other WeWork executives described the company “at various times… as a community company, a lifestyle company and a platform for entrepreneurs.”

Neumann went on to add, “we ourselves are still discovering what is the best type of company that we want to be. We’re taking the best practices out of the for-profit world and best practices out of the nonprofit world.”

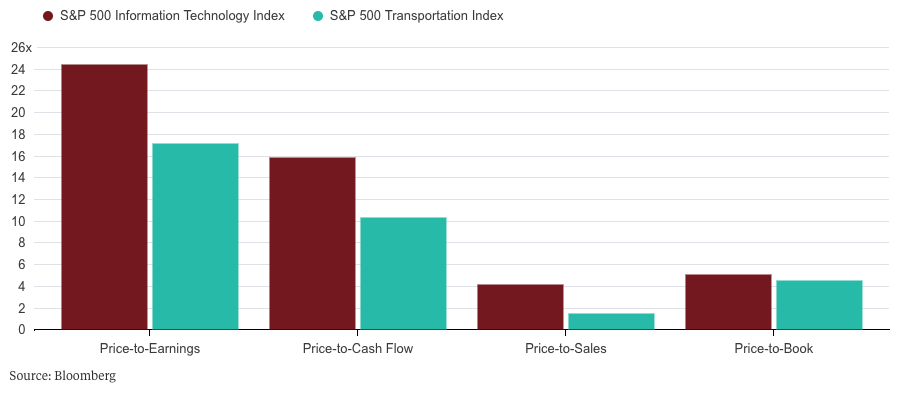

Skeptics continue to question whether WeWork should receive the tech company treatment, especially in valuation, when real estate is so integral to its main product and subsidiaries. In addition to co-working space, WeWork dabbles in communal housing, early education, and, strangely, a wave pool business.

WeLive, WeWork’s attempt to infiltrate the residential real estate industry, features shared expansive kitchens, large laundry rooms with ping pong tables and other interactive amenities, and free WeWork cocktails on rooftop terraces and in mail-room themed bars. That’s right, what serves as the WeLive mailroom during the day is converted into a happening bar at night designed to bring the inhabitants together to socialize and expand their network.

Bloomberg Technology noted that “WeWork wants to parlay its success with co-working into a “we” lifestyle brand that incorporates not just work but living and wellness for community-minded people.

Similar to other tech-giant influencers like Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, the WeWork co-founders have taken a keen interest in early education. In Fall 2018, the company is set to open a private elementary school for “conscious entrepreneurship” inside an New York City WeWork space. The experimental school was tested via a pilot program of seven students, including one of the five children of WeWork Co-founder Adam and Rebekah Neumann.

The project is being spearheaded mostly by Rebekah Neumann, who attended the prestigious New York City prep school Horace Mann and received a bachelor’s degree in Buddhism and business from Cornell University. She told Bloomberg the school will “(rethink) the whole idea of what an education means” but is “non-compromising” on academic standards.

“In my book,” she stated, “there’s no reason why children in elementary schools can’t be launching their own businesses.” Can anyone say, “Baby Boss?”

The most peculiar industry expansion for WeWork, however, was the purchase of a “large stake” in Wavegarden, a wave-pool start up. It remains unclear how Wavegarden’s technology, which can produce up to eight-foot-high waves for surfing at various water facilities, fits with WeWork’s common-space persona. A company spokesperson told the Wall Stret Journal that WeWork has “made meaningful investments to significantly enhance (the company’s) product offering.”

Throughout the various expansions and acquisitions of the WeWork brand, one narrative has remained the same: “the “we” brand promotes a seamless integration of meaningful work and a purpose-driven existence.

The “We” model has proved popular. As of October this year, WeWork established itself in 172 locations in 18 countries, granting its 150,000 a variety of locations to work from. The workspace provider employs over 3,000 people. The startup is rounding out the year with an impressive purchase of the social network company Meetup which strives to connect individuals during their off-work hours based on common interests. WeWork hopes the acquisition will help establish a sense of community in its shared workspaces, Inc. reported. The most valuable component of the purchase, however, is Meetup’s 35 million user base.

Some Silicon Valley investors and others in the real-estate industry say the company’s well-crafted image belies the unremarkable nature of its business. For instance, let’s consider WeWork’s competitors. With an indeterminate identity, it is hard to say just who WeWork’s competitors are or if the company even has any contenders due to its multitude of market engagements. IWG PLC, an office-leasing company with a similar business model to WeWork, manages five times the square footage and has approximately one-eighth the market value. Boston Properties Inc., the United State’s largest publically traded office leaser, owns five times the square footage that WeWork leases and manages while boasting a market capitalization of $19 billion.

Barry Sternlicht, who runs Starwood Capital Group LLC with more than $50 billion of real-estate assets under management, said, “if you had positioned (WeWork) as a real-estate company, it wouldn’t be worth (its valuation).” Neumann “dressed it up and made it into a community, and that turned it into a tech play” he said.

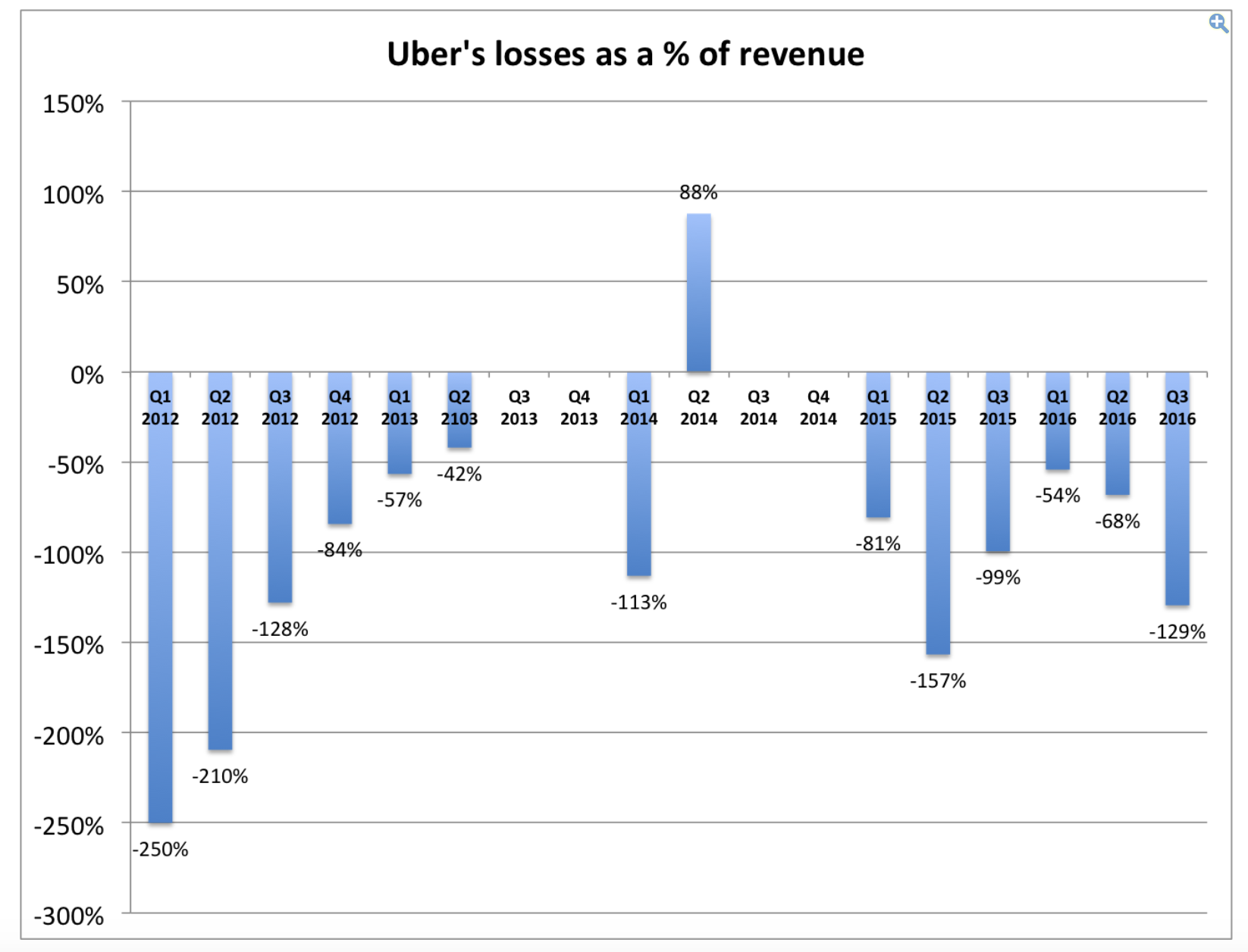

One argument against WeWork surrounds it’s “expanding” clientele base. A large portion of WeWorks client base is comprised of startups. If there were to be a downturn in the market, it would become increasingly difficult for startups to raise funding. If startups don’t have the funding necessary to sustain themselves, WeWork might run into trouble staying profitable with a decrease in leasing demand as its clients wouldn’t be able to pay the rent for the office space.

WeWork was swift to negate any doomsday arguments, stating that only a small fraction of its client base are other tech startups. “Venture capital-backed companies only makeup mid-single digit of the total population of our WeWork member companies,” a spokesperson told Business Insider. “The membership is very diversified across multiple industries and our fastest growing segment is larger, more mature companies who have joined for the value proposition of more affordable space, community, networking, and flexibility – as well as services (healthcare, payment processing, etc.)”.

Despite the company’s efforts to assuage any skepticism, many academics and industry experts remain unsold. Consider the passionate words of Scott Galloway, a marketing professor at the NYU Stern School of Business and the founder of business intelligence firm L2, said in a Business Insider presentation, “WeWork is arguably the most overvalued company in the world. WeWork is now getting a valuation equivalent of $550,000 per customer… In some instances, WeWork – if you do the math – the floor that the WeWork (office) leases in a building is worth more than the building hosting the WeWork.”

Galloway went on to compare the co-working space to other tech companies like Snap, Inc. and Twitter, “Snap is incredibly overvalued, WeWork is incredibly overvalued, and a company that’s off (its market estimation) 70%, Twitter, is still massively overvalued. (Twitter) is a stock that will be trading for between five and ten bucks within six to 12 months. Two and a half years ago, when it was at 55 (dollars per share), I said it would be below ten, and I was wrong, it’ll be below five.

It is unclear whether WeWork will have a similar rocky post-valuation experience to Twitter and Snap, Inc. with so much tech industry confidence balancing out the vocal skepticism.

From WeWork’s commencing days, Neumann would preemptively boast about how he was building a $100 billion business to his friends. With a $20 billion valuation under WeWork’s belt, the co-founder’s brag might not be terribly outlandish after all. Does the company actually deserve its high appraisal? Will WeWork be a startup that simply dazzled the tech industry in its 15-seconds of fame? Only time will tell, but for now, WeWork is confidently looking towards the future and not letting criticism get in its way.