Labor strike has a long history since the industrial revolution, dating back to early 19th century in Europe. It is rarely a top news today. The barista who made a coffee for you at Starbucks, the cleaner who mopped the floor at McDonalds, and your favorite barber at the street corner, may have once protested on the streets.

It won’t disturb you too much under most circumstances, unless, for example, the angry railway workers make the company cancel your train. But to some extent, the labor strike can tell you what’s happening to our economy, which might somehow impact your life.

Worker strikes can have a wide range of incentives, and in this blog we focus on the economic ones, that is, those over mandatory issues such as wages, working hours, union rights and so on. It is not hard to detect that the number of economic strikes fluctuate yearly. At certain points the workers seem much more proactive than usual, and we can name this phenomenon as the strike cycle. Does it remind you of something? Our economy has periodic expansion and recession too, referred to as the business cycle. Does these two cycles correlate?

Conceivably, it is assumed that strikes occur more frequently and last longer at the period of economic recession; the album of economic depression always contains the pictures of desperate penniless workers marching on the roads. The employers intend to lower the wages and dismiss the employees in an attempt to make their shrinking business survive, consequently arousing disputes and frustrations. However, regarding the demand and the supply of the job market, it is also likely that employees are less inclined to strike when they are at a risk of being crowded-out, while their bargaining power improves during economic expansion. If the workers are rational and self-interested, seemingly they will not irritate their boss when they are losing money.

What Studies on Historical Data Tell Us

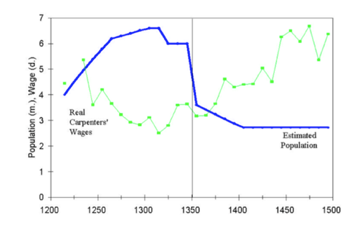

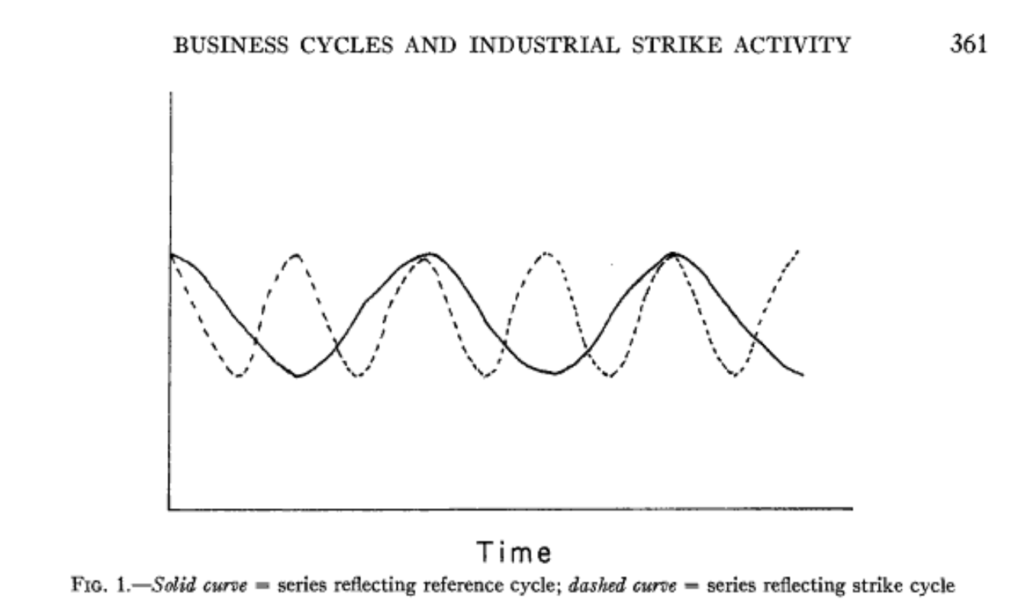

A 1952 study by Rees compares the Bureau of Labor Statistics(BLS) series on monthly strikes with the reference business cycle of the National Bureau of Economic Research(NBER) after WWI. It concludes that there is a significant conformity between the two cycles, and the strike peak constantly precedes the business one (Figure 1). Rees explains that the strike represents the tension between union and employers. When the economic expansion is starting, the union has higher expectations while the employers react negatively to it, so their divergence reaches the maximum level.

Some scholars focus on the the relations between strike duration and the business cycle instead. The Institute for the Study of Labor issued a paper in 2008, citing over ten thousand strikes recorded by the Engineering Employers Federation in Great Britain from 1920 to 1970. It discovered that the labor strike duration is countercyclical, that is, the strike will last longer at the time of economic upturn. Additionally, higher employment rate usually enables the union to achieve better outcomes.

It should be noticed that some economists are highly suspicious of the strike data as an economic indicator, concerning that (1) the strike can be driven by political activities such as election and political campaign; (2)the strikes, like many human activities, can be random and irrational. Scully wrote after studying the strike cycle in mid-20th century that “there is no relationship between the strike cycle and the business cycle” in the long term (while in the short run they do correlate).

Work Stoppage and Economic Cycle in Post-WWII U.S.

What does the labor strike data tell us about the U.S. economics in the past 80 years?

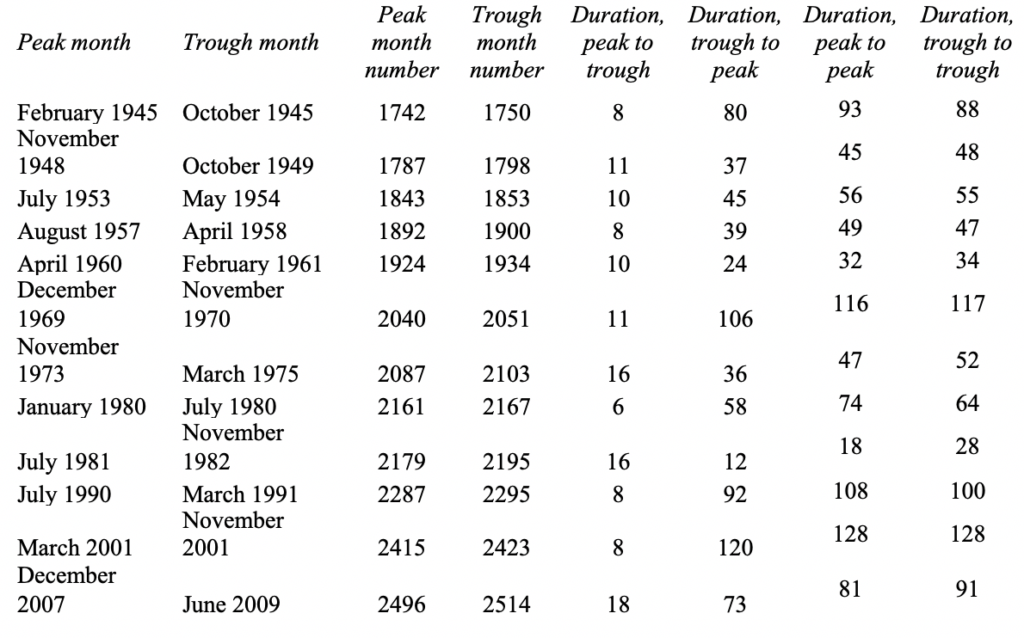

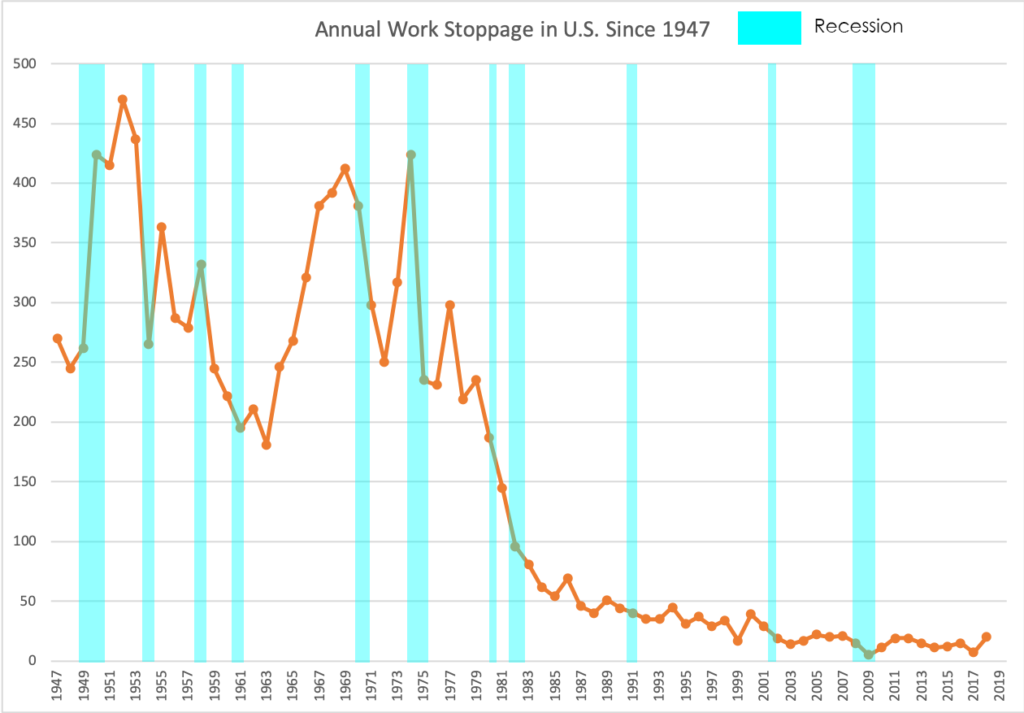

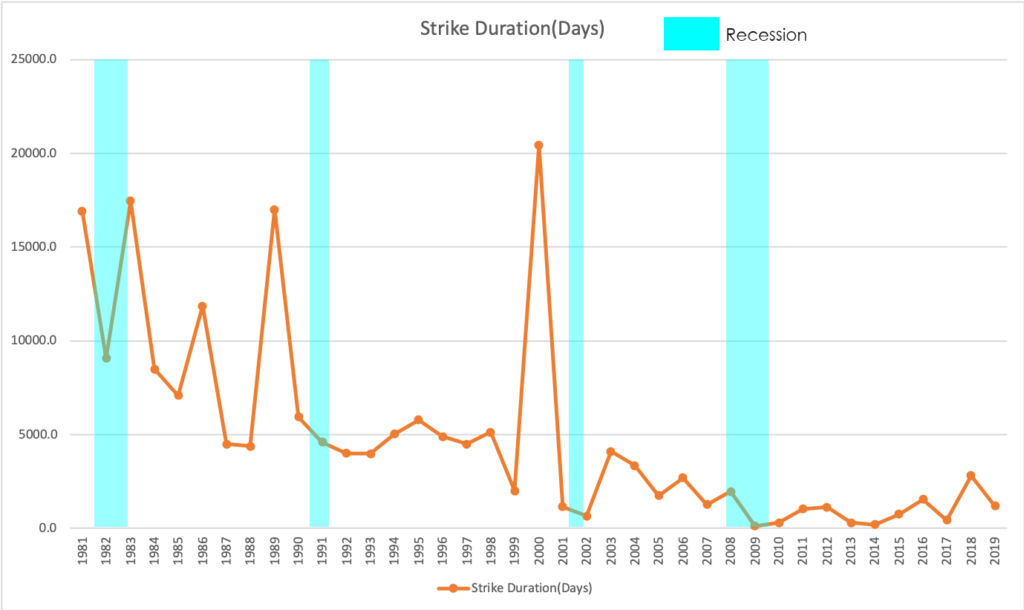

According to BLS statistics, the number of labor strikes in U.S. since 1940s has gradually declined, while still having a cyclical pattern (Figure 2). BLS only recorded the days of idleness since 1980s, and it also displayed similar pattern(Figure 3). With reference to the business cycle defined by NBER (Table 1), it is found out that the strike frequency never peaked during the recession. Except for 1948-1950 and 1957-1958 recession, when the economy is shrinking, workers are less inclined to protest on streets than they were in the previous year. When it comes to the strike duration, such correlation is less apparent, partly due to the lack of statistics. But it is still safe to claim that labor strikes usually lasted shorter than last year if the economic downturn is going on.

The above-mentioned evidences support the argument that labor strikes increase as the economy booms in order to maximize the union’s bargaining power. Nevertheless, business cycle can not account for all the characteristics of the strike cycle. For instance, the fluctuation of labor strike became very minor after 1990s, and it did not rise up significantly from 1991 to 2001 when the economic blossomed for almost a decade. Potential explanations lie in the development of union trades and labor rights legislation.

In conclusion, Labor strike data reflects the union’s behaviors as rational players in the economy. Trade unions are more likely to organize working stoppage when the business cycle is at its top, and workers are less likely to protest when the economy is falling down and offering less jobs. However, given that other factors especially the political events also exert an essential impact on trade union’s decision-making, it requires more caution to treat strike data as an economic indicator.

Reference

Scully, G. (1971). Business Cycles and Industrial Strike Activity. The Journal of Business, 44(4), 359-374. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2352052

Rees, A. (1952). Industrial Conflict and Business Fluctuations. Journal of Political Economy, 60(5), 371-382. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1826482

Devereux, P. J., & Hart, R. A. (2011). A good time to stay out? Strikes and the business cycle. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 49, s70-s92.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/

The National Bureau of Economic Research.https://www.nber.org/cycles/recessions.html