Norwegian Air made headlines earlier this year when it advertised flights between the United States and Europe for as low as $65. It was unthinkable. No airline could possibly pull it off.

But Norwegian has created a new business model as a low-cost long-haul airline, riding on a wave of innovation from airplane manufacturers. Thanks to the fuel-efficient Boeing 787 Dreamliner and 737 MAX, it’s now possible for airlines to fly relatively small jet planes between far-off destinations and avoid the expense of flying large planes through large and costly airports.

This link between the airplane business and the airline business is strong and has been for decades. But it takes years for a concept for a new plane to become a flyable reality, so aerospace companies are always trying to predict the future: what will airlines and their customers want?

Bombardier is trying to do for domestic and regional flights what the 787 Dreamliner did for international travel. With its C Series, an entirely new 100- to 160-seat plane built with modern technology, the Canadian aerospace giant is betting that the future of air travel is direct flights between destinations on smaller planes rather than large flights through crowded hubs.

But the C Series program has been plagued by trouble, and other manufacturers are jumping at the chance to be first to the point-to-point air travel future. Boeing took action that led to hefty tariffs on Bombardier’s jets, and Airbus has since acquired a majority stake in the program.

As airlines phase out their large planes, what happens next will decide who dominates the airplane market for years to come.

A brief history

Prior to 1978, air travel in the United States was heavily regulated by the U.S. government. A federal agency dictated routes that airlines had to run, the fares they were allowed to charge for those routes, and how frequently they had to serve them. These mandates limited the ability of the industry to respond to changes in demand or fuel prices and the ability of individual airlines to innovate or compete with one another.

The deregulation of airlines in 1978 led to a period of rapid change in the industry, with most airlines coalescing by the end of the 1980s around what has become known as the hub-and-spoke model.

In a hub-and-spoke airline network, flights from “spoke” airports in smaller cities fly toward a larger “hub” airport, with the arrivals timed so that passengers can connect to other flights at the hub and fly to their destination. For example, a traveler leaving Oklahoma City headed for New York City could fly to Chicago first and connect there to a New York-bound flight. The system made up for uneven demand across cities by consolidating passengers headed for one destination onto one route.

The hub-and-spoke system enables airlines to provide more frequent service on larger aircraft at a lower per-passenger cost, creating an economic incentive for aerospace companies to design and produce larger planes. Its primary alternative, a point-to-point network, encourages the opposite: fast and frequent service on comparatively small — or “right-sized” — planes. This model was first popularized by Southwest Airlines, which has transformed the airline industry since its nationwide launch in the 1990s.

Avoiding a stop at a hub reduces costs by up to 30 percent, researchers at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University found, and those savings can be passed on to the passenger. In a hub-and-spoke system, many flights arrive at a hub airport within a short time period and then depart together somewhat later. This increases congestion at the airport and means that planes and staff go unused between groupings of flights. Additionally, nonstop point-to-point service reduces the need for ticketing agents, gates, lounges, and baggage facilities by spreading demand throughout the day.

How aerospace companies respond

These different models of airline routing demand different kinds of planes, which has shaped the strategies of plane manufacturers over time. Research and development for a new model of airplane takes years, sometimes up to a decade from conception to delivery. This is a huge investment of resources for the manufacturers, so they try to anticipate trends years in advance.

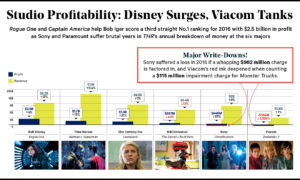

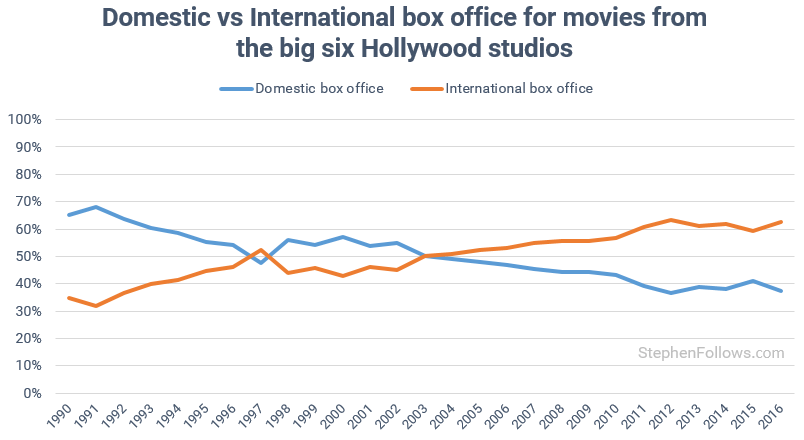

But sometimes the big players don’t agree on where things are headed. Looking at the programs that duopolistic Airbus and Boeing pursued throughout the 2000s, we see diverging trends: Airbus believed that bigger planes would bring costs down through economies of scale, while Boeing thought efficiency would help midsize planes travel more cost-effectively over long distances.

The Airbus A380 program officially began in December 2000 with the goal of allowing high-capacity flights between hub airports at a low per-passenger cost — consistent with the hub-and-spoke model. Airbus has described this as a necessary response to growing demand for air travel, which it says will lead to overall air traffic doubling every 15 years. Years after its release, the A380 remains the world’s only double-decker plane, able to carry more than 600 passengers over distances of more than 15,000 km.

But it seems that Airbus made the wrong choice in pursuing size over economy. Very few cities have passenger counts that could reliably fill a 600-seat plane, and the four jet engines on the A380 mean that flying one that isn’t full becomes prohibitively expensive. Not a single airline in the United States has purchased an A380, and their attitude toward large planes is shown in their treatment of its closest equivalent, the iconic Boeing 747: all American airlines plan to retire their 747s by the end of this year.

“Every conceivably bad idea that anyone’s ever had about the aviation industry is embodied in [the A380],” aerospace analyst Richard Aboulafia told the New York Times.

Airbus initially predicted it would sell 1,200 of its superjumbos within two decades of launching, but the most recent data show that only 317 have been ordered.

Thousands of miles away in Washington state, Boeing was developing a different kind of airplane: one efficient enough to fly the longest routes in the world and small enough to avoid overcrowded hub airports.

With the 787 Dreamliner, Boeing used composite materials rather than metal to create a plane far lighter than its peers, saving up to 40,000 pounds. This, combined with more efficient engines and battery-based systems, made the plane 20 percent more fuel-efficient, bringing costs down to levels that made a 300-seat plane appealing to airlines flying international routes.

Despite launching commercial service four years after the A380 and being grounded worldwide for months due to early safety concerns, the 787 has sold three times as many planes as the Airbus superjumbo, with 1,283 orders as of Oct. 31.

Going even smaller

Bombardier, looking to the success of efficient planes and point-to-point networks, has tried to scale down the business model of Boeing’s 787. In 2008, it publicly announced the C Series, a line of small jets that could seat between 100 and 160 passengers. This placed it in the market between an increasingly popular line of regional jets from Brazilian firm Embraer and the ubiquitous Boeing 737 and Airbus A320 series mainline jets. Bombardier expected to sell more than 3,500 planes in this market within 20 years.

The C Series was designed to increase efficiency on domestic routes, and its smaller size is meant to make it feasible for shorter runways at smaller airports while still allowing more passengers than a regional jet. Bombardier says it will “let operators open more new routes and offer the frequency being demanded by passengers, without increasing costs.”

Bombardier and the governments of Canada, Quebec and the United Kingdom all invested heavily in the development of the C Series, totaling about $4.4 billion by early 2015 — or about two-thirds of Bombardier’s market value at the time.

“We all kind of loosely used [the term] ‘betting the company’” to describe the project, former Bombardier Commercial Aircraft president Gary Scott told the Wall Street Journal.

But the company has struggle to make that big investment worthwhile. New technology meant the C Series could be more efficient than other airplanes, but fuel prices began plummeting soon after the project was announced, and production delays eliminated the first mover advantage that Bombardier had over Boeing and Airbus. Both the big players quickly launched new versions of their 737 and A320 series with more efficient engines, something that Bombardier hadn’t anticipated.

Competing directly against Boeing and Airbus proved difficult for Bombardier, which in the past avoided such competition by focusing on smaller regional jets. After Delta Airlines placed an order for 75 C Series jets, Boeing began demanding the U.S. Department of Commerce place a tariff on those planes, which would be produced with what it called a Canadian government subsidy. The government agreed, levying a 300% tariff on the C Series.

To save the program from extinction, Bombardier gave half the C Series program to Airbus at not cost. Since Airbus has more resources, U.S.-based manufacturing plants, and worldwide service centers, it’ll be able to sidestep the tariff and make the C Series more appealing to airlines. Plus, Airbus gets to benefit from the revenue on a plane it paid nothing to develop.

This fierce and somewhat unprecedented battle over small jets signals a major shift in the industry and perhaps the end of the reign of hub-and-spoke networks. Airbus has said it expects to sell up to 6,000 C Series planes in the next 20 years, which make the new category nearly as widespread as its own A320 family, one of the world’s most common planes.

Looking ahead

As air travel demands increase and large airports become more crowded, planes like the C Series will allow airlines to more completely meet passenger demand, flying “long and thin” routes between cities that are too far from each other for regional jets to travel but don’t have enough demand to profitably maintain service with something like a 737 or A320.

According to Embry-Riddle researchers, only about 5 percent of airport pairs in the U.S. could sustain nonstop point-to-point service on mainline jets. For an airline like Southwest that flies only Boeing 737s, it would be hard to break into markets with unsatisfied demand.

But a plane like the C Series could open new markets to air travel, and that’s why aerospace companies are vying for pieces of this new segment. At an airport with short runways like London City Airport, the C Series can go twice as far as any other aircraft and with 25 percent more passengers, Bombardier program head Rob Dewar told The Globe and Mail. For other airports like this around the world, a new generation of planes can create new routing possibilities, expanding the reach of point-to-point networks to places they couldn’t have gone before.