No One Can Copy the Taste of Coca-Cola:

Predicting Hollywood’s Influence on Chinese Cinema from the Case Study of French Cinema

Yutai Han

JOUR469

12.6.2017

In this paper I ask the question: what was Hollywood’s influence on world cinema and on the domestic market, in particular, I look into the history of Hollywood’s impact on French cinema from the Nouvelle Vague to the recent years. Because of the richness of the history of French cinema and the success of cultural policies that counteracted Hollywood’s impact and maintained opportunities for local filmmakers, the case of the French cinema provides an ideal example to analyze the future of China’s domestic film industry. This question is inspired by my previous inquiry into the Chinese film market and China’s failed investments in Hollywood. In my last blog post and presentation, I claimed that it is possible that due to Beijing’s tightened control on investments leaving offshore, Hollywood is losing their bet on Chinese money saving the day, and that China will continually focus more on domestic film productions and will probably impose the same, if not less and harsher, limits and rules on the number of films that are allowed to be exhibited in mainland China each year, as a new negotiation is set to take place this year that will decide on the issue.

Zhang Yimou, a well-known Chinese film director, published a commentary titled “What Hollywood Looks Like From China” on The New York Times on Monday in which he asked what China’s film industry gain in return while Chinese audiences provide Hollywood with huge profits. He wrote, “…homegrown movies in China sometimes face steep challenges in the shadow of Hollywood blockbusters. We are right to be concerned about the succession and inheritance of China’s film traditions as well as the potential loss of our unique values and aesthetics.” To put this letter in more context, in 2017, according to official data from the Chinese “Ministry of Truth” (The State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television of the People’s Republic of China), the market is rosy. As of November 20th, 2017, the box office in China has exceeded 50 billion yuan ($7.54 billion), which is a 19 percent up from last year. Domestic films grossed 26.2 billion yuan (52.4%) in total while foreign imports grossed 23.8 billion yuan (47.6%). Among the top ten highest grossing films in China, five films are Hollywood productions. The biggest contribution to the domestic film market this year is Wolf Worrier 2, a nationalist propaganda film that grossed $862 million in the summer of “domestic film protection month”. From the research from my last presentation, I found data that shows only 7.7 percent of worldwide net revenue came from China. Although that’s not a large percentage, but Hollywood’s impact on Chinese audience’s viewing habit is still significant, as the top ten grossing list has shown. I shall discuss this more in the third part of my article.

1. Summary of Hollywood’s Influence on World Cinema

The artistic and economic impact of Hollywood’s blockbusters on the local film industry have been widely studied. Diana Crane, professor of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote that “The quantitative analysis shows the domination of the US film industry in almost every region. American films and American co-productions dominate the lists of top 10 films in the global market and in national markets in spite of protectionist cultural policies and national subsidies in many countries.” Moreover, Hollywood’s need for return on investment in blockbuster productions, the most prominent case being Marvel’s superhero franchise, has led to changes in content toward “deculturalized, transnational films, a trend that is also evident in other countries.” (Crane) In order to attract global audiences, Crane claims that “the content of Hollywood films has been transformed. The levels of violence, action, sex, and fantasy, all of which can be conveyed visually rather than through dialogue, have steadily increased in Hollywood films.”

Indeed, at least in my viewing experience of Hollywood productions that came out in recent years and those from the earlier period, there exists a noticeable change of narrative, form and content. De zoysa and Newman argue that “the mythical golden years of Hollywood spanning 1938–1960 (which) projected a uniform vision: faith in the democratic order, the classless society, heroic individualism and the golden opportunities offered by the capitalist work ethic and enterprise.” However, in recent years, and in particular this year, I noticed that film as an art form started to change fundamentally. No matter the genre and production budget, film-making is becoming more and more an industrialized factory of flat, boring, transnational works of literal depictions of events, and less and less a cultural artifact that may revoke emotional responses and inspire individual expression. Here, I quote Crane’s summary of the trend of“transnationality”, “Films in other countries and regions, such as China, East Asia, Scandinavia and other parts of Europe, are also becoming transnational. They are likely to be less rooted in their national cultures and more likely to incorporate perspectives from other countries in order to attract audiences in the global film market.” (Crane) One example that helps to make sense of the issue is a scene in Alfonso Cuarón’s post-apocalyptic film Children of Men, in which an art collector gathered famous art pieces in a monotoned, large room. Michelangelo’s David is seen as just a giant piece of sculpture, missing an ankle and bared out of its original meaning. This scene can be understood as a statement that corresponds to the issue facing the film industry. If art is taken away from its cultural background, then there is no art. Michelangelo’s sculptures cannot leave their chapels in Italy, just as Hollywood films will lose the glamour if they’re forced to adapt to a global context in order to appeal to foreign markets. Moreover, in film, the audience can discern the fake elements instantly, and avoid the film, which can result in an unsatisfying box office, such as The Great Wall (2016). Think in terms of Coca-cola and companies trying to copy its taste: we will know instantly, in the first sip, that the fake Coca-Cola is inferior to the taste of the real Coke that is manufactured and bottled in the United States. But everyone knows that the coke never “conquers the thirst”—it only leaves us wanting more.

2. History of French Cinema and French Cultural Policies

I have already established that film is a distinctive cultural artifact that has significant symbolic and artistic value. Now, let’s look at film from an economic perspective. Specifically, in France. What policies did France enact to lessen or counteract Hollywood’s impact on their domestic film industry? After the Second World War, France imposed quotas on the number of American films, and reserved screen times for domestic films. The youth who grew up during that time of France, watched a lot of these films and formed their perspective of how films should be made. The young Godard and Truffaut, who would later become master directors and would influence Hollywood directors and Asian directors like Tarantino (Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill), Alfonso Cuarón (Harry Potter and the Prisoners of Azkaban), and Wong Kar-wai (Chunking Express, In the Mood for Love), were so critical about the Hollywood productions and domestic films that they launched their own career as film review journalists. Their journalistic efforts and devotion to art contributed to the formation of the film movement known as The New Wave. “It was the sudden rush of creation in the late fifties that led France’s then-Minister of Culture, André Malraux, to introduce a series of measures intended to promote the production and distribution of French movies not just as commercial ventures but as works of art that would be fundamental to France’s cultural heritage. The New Wave directors themselves, at least in the early years, hardly benefited from this system, which, however, reinforced their critical legacy—that of the auteur, the individual creator, as the key element in movie production—as the image of the French cinema as marketed to the world.” (Brody, The New Yorker)

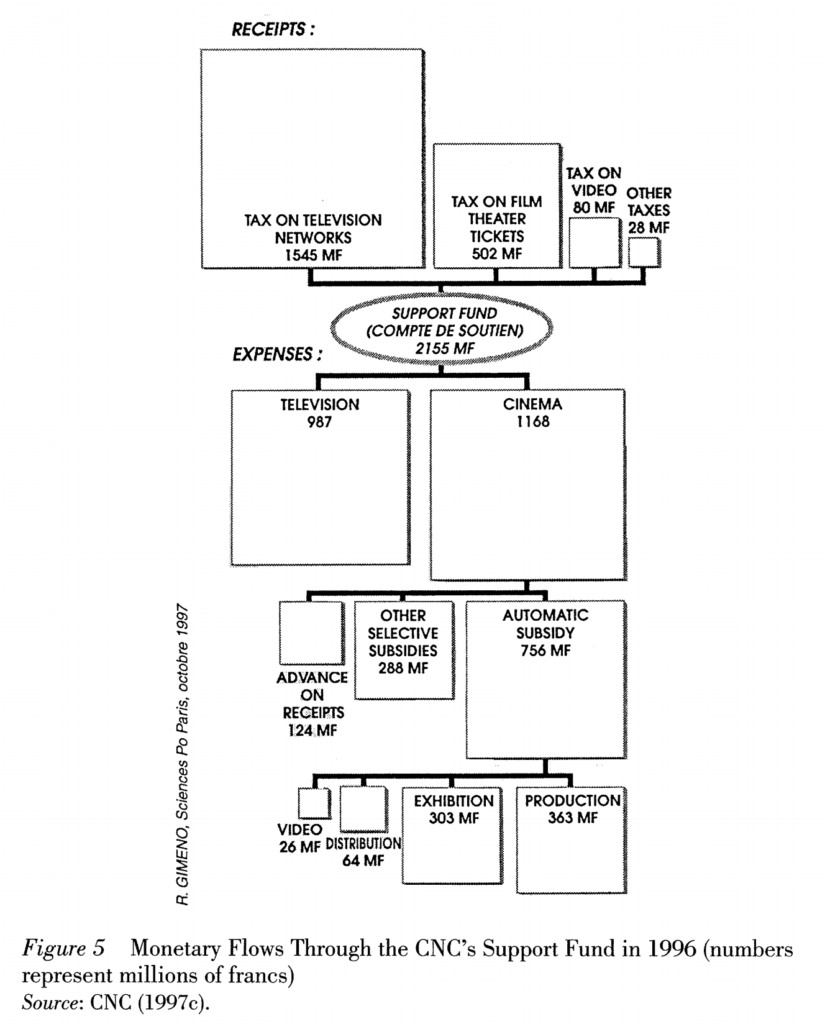

This idea of filmmaking, that serving cultural interests takes priority over economic gains, has been central to the French film industry and policy-making, and it is why French cinema didn’t decline as severely as it has in Italy, Germany and Britain. (Scott, 27) The cultural policies are “an intricate combination of financial subsidies, induced investments, television broadcasting quotas, managed labor markets and the many and varied services provided by the CNC [The National Center for Cinematography and Moving Image] to the film industry.” (Id.)

(Image: Allen J. Scott, Economy, Policy and Place in the Making of a Cultural-Products Industry)

These cultural policies led to an increase of the number of French films produced annually, from 89 in 1994 to 230 in 2009. (Crane) However, it has been reported that three-quarters of French films do not recover their costs. And as a result, some French filmmakers are going in the same direction as Hollywood, imitating the style (“transnational” films), the process of production, and hiring international casts and crew. These films have been “much more successful in attracting foreign audiences.” (Id.)

This is the underlying problem of the the film industry that every country must face. In Brody’s article, he says “creation can be managed but not popularity: the government may foster the production of films that are aimed at wide audiences but can’t make the audiences buy tickets.” Therefore, in terms of the economy of scale, because Hollywood has been the center of the film industry since the 1920s, it’s able to develop and maintain the order of things in a way that other nations are unable to compete with.

3. Discussion on the Future of Chinese Film Industry

Finally, we are back to the main concern of this article. From 1 and 2, I have laid out why Hollywood can have a significant advantage over local film productions. Local film markets, such as that of France, are unable to compete with the “build quality” (glamours of the stars, “transnational” narrative structure, visual effects) and the marketing ability (roughly a third of the budget goes to promotion) that Hollywood gained throughout the years. Furthermore, Hollywood is able to maintain its economy of scale in today’s global film industry, despite cultural policies taking place. In light of this over-arching tension, I begin my discussion of my prediction on China.

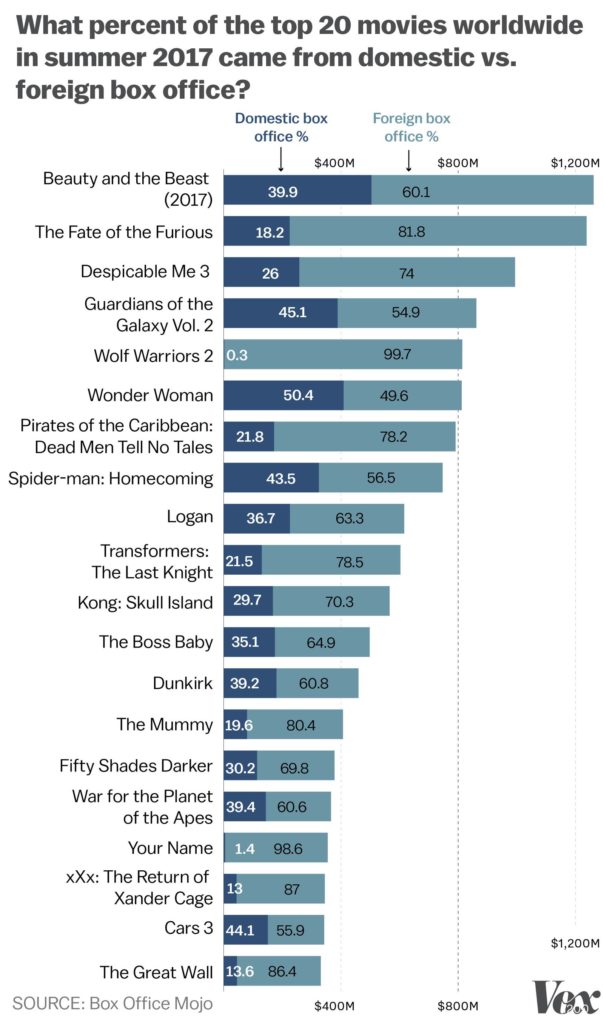

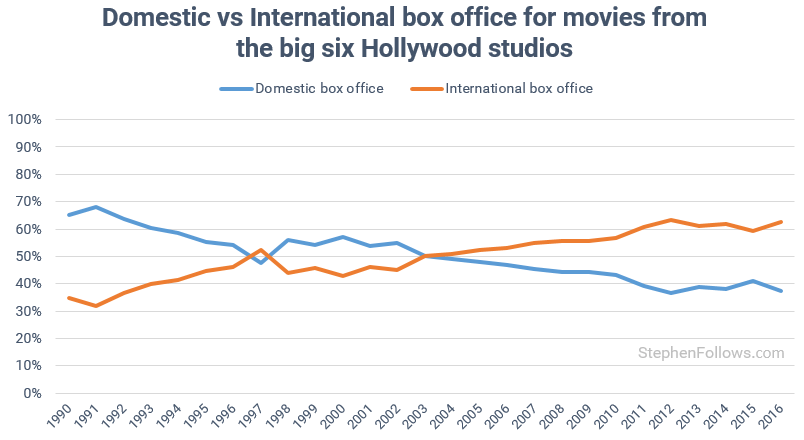

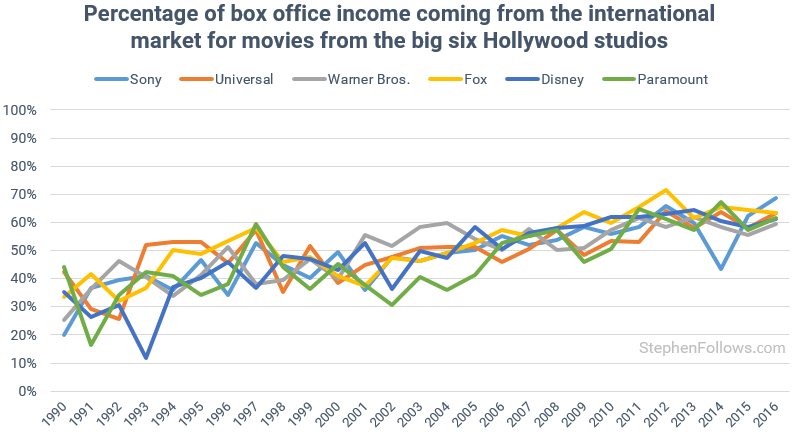

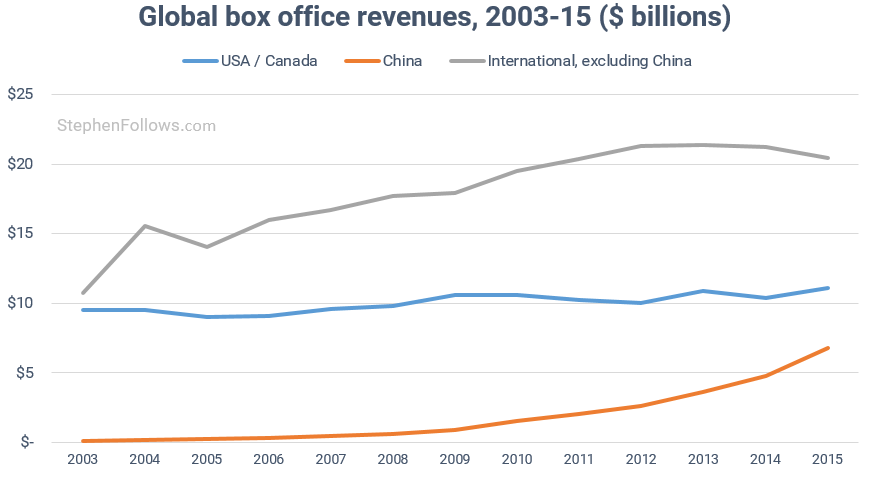

First, under normal circumstances that the quota don’t decrease, China will contribute more to the foreign box office of Hollywood productions. Figure 3.1-3.3 demonstrates that as a general trend, Hollywood derives more profit from the foreign box office than the domestic box office, and it will be the predominant factor for production in the future. It’s possible that domestic box office will continue to decrease, while the foreign box office will continue to grow. China is the major contributor for that growth (figure 3.4).

(figure 3.1)

(figure 3.2; source: https://stephenfollows.com/important-international-box-office-hollywood/, same below)

(figure 3.3)

(figure 3.4)

Every school in China has English lessons, and the youth grew up watching Hollywood films and TV shows. The online forums for fans are robust, and they would wait for a new episode of an American TV show impatiently. This appetite doesn’t reflect on the box office records, but it’s safe to say that the youth are hooked to American entertainment. If a production is phenomenal in itself and received a positive review, such as Nolan’s Interstellar and Inception, or Pixar’s Coco, which scored a record box office in its first weekend opening in China, then the film will be successful in the Chinese market. Hollywood studios need not tailor their films for the Chinese audiences.

Second, since investments are down due to government regulations and conflicts of power, the investors will shift their direction to favor more domestic projects. This will result in a wave of young filmmakers trying to make a name out of themselves. Wang Jianlin, the CEO of Wanda, which owns Legendary Entertainment and AMC, said in a TV interview that he wants to “have an award show like the Oscars and the Golden Globes in China” and that “no one told me to show Chinese films in AMC (in the United States), but I did.” His son, a well-known social media personality, recently launched a multi-million yuan campaign aimed to find the best young directors and offer them filmmaking resources.

Third, internet studios, such as Alibaba’s Youku, Baidu’s iQiyi and Tencent Video, have announced ambitious plans to develop original series. Arguably, the success of original shows produced by Netflix and Amazon Studios is the inspiration for the Chinese counterparts. In fact, the biggest internet companies in China has followed its U.S. counterpart’s footsteps, and it’s no coincidence that the Chinese internet studios are investing in their original series. However, this wave of big capital flowing through the market may result in a negative way in terms of the production’s artistic value. In fact, there is evidence that Chinese production companies are flipping the market before the film is made. One report says that according to sources, insider trading and splitting shares are not unusual.

—

References:

Crane, Diana. “Cultural Globalization and the Dominance of the American Film Industry: Cultural Policies, National Film Industries, and Transnational Film.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 20.4 (2013): 365–382. Web.

De Zoysa, Richard, and Otto Newman. “Globalization, Soft Power and the Challenge of Hollywood.” Contemporary Politics 8.3 (2010): 185–202. Web.

Scott, Allen J. “French Cinema.” Theory, Culture & Society 17.1 (2016): 1–38. Web.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.