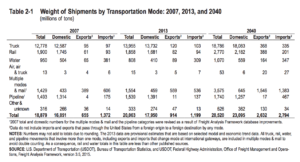

Trucking is the backbone of the U.S. and international supply chain, delivering and exporting nearly 13 billion tons of finished and unfinished goods from factories overseas to doorsteps across America and vice versa. The next step in trucking — taking drivers out of the equation — will yield cheaper consumer goods and safety but could cause unemployment for well over three million people.

Uber has been investing in self-driving technology since launching their Advanced Technologies Group in 2015 out of Pittsburgh. While most companies are still focused on autonomous cars, Uber has started developing autonomous trucks in their division Otto.

One of their competitors, a startup called Embark, just received series A funding for $17 million. Embark has partnered with trucking manufacturer Peterbilt, which will undoubtedly give them a leg up against other self-driving truck companies.

Google has also entered the self-driving truck sphere too with Waymo, its autonomous driving division. Google sued Uber for taking its proprietary laser systems that they used for self-driving capabilities. A former manager at Waymo illegally downloaded information that he used to found Otto.

These three self-driving competitors could threaten nearly two million jobs according to an Obama era White House report, though no one can really say when that will happen and many disagree on a time frame.

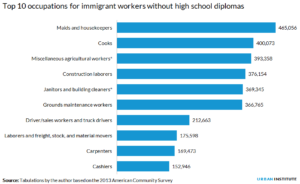

The industry is dominated by white males with an average age of 45. Around 95 percent of people who work in the industry are male and 75 percent are white. That matches up surprisingly well with the rest of the U.S., which is 77 percent white. So therefore, most people who drive trucks in the US, and who could also be displaced by automation, make up a large majority of the population. If trucking were to ever be completely automated in anyway a large portion of the workforce will go away and have trouble finding another line of work.

Some experts including economic sociology lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania, Steve Viscelli, disagree with the dire estimates some people, like the White House, are floating.

“There’s a dichotomy of it’s either never gonna happen is one response or it’s going to happen and we’re going to lose 3 million trucking jobs,” Viscelli said. He admits it’s hard to tell with tight-lipped Silicon Valley executives.

Still, based on the research he’s done for his book, The Big Rig, which explores how long-haul trucking has declined recently, there are many obstacles that these companies need to surmount before automation can replace jobs.

The mechanization of non-driving movement, the one thing that truck drivers have over automation, is a problem that has to be solved if big rig automation will take over the human element, Viscelli said. Port to warehouse and/or store trips will likely happen sooner as there are less tedious steps in between. In those direct routes, all the truck has to do is drive.

But for places that don’t have easily accessible loading docks or none at all and have variables that aren’t taken accounted for in the computer, trucking companies will still need humans to drive. There are other tasks that truck drivers do — opening and closing doors, inspecting the truck, performing ad hoc maintenance and driving in narrow city streets filled with pedestrians — that a robot simply can’t do and won’t be able to do any time soon on a large scale.

Viscelli estimates that real labor disruption won’t take place for at least three to ten years.

Mapping roads in a way that is compatible with these trucks is yet another problem. Google claims that they have mapped 99 percent of public roads in the United States, as of 2014. But, that’s only including public roads. There are just over four million miles of paved roads in America, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Even if that is only including public roads, they haven’t covered around 40 thousand miles of roads, or 8 round trips from L.A. to Miami. A massive investment of time is required to make sure maps provide a good enough base to automate with.

Viscelli said basic sensor limitations hold back trucking as well. Most light detection and ranging (LIDAR) systems in use on these prototype trucks can only see at three to four hundred feet. Driving at 55 miles per hour, it will take over 400 feet to stop a truck with an air brake system according to the Department of Motor Vehicles. Waymo’s truck also uses ultrasonic sensors and radar.

Integrating and processing nearly 6 million data points every few seconds from different sensors requires a lot of computational power and technical computer programming, also adding to the time it will take for these trucks to be pervasive on the road.

In an economic sense, the cost-benefit analysis doesn’t make sense yet. It will cost more to total a truck due and possibly kill people on the road due to faulty automation programming or equipment.

Jerry Lake, who runs a trucking business with his son and wife out of small-town Montrose, Colorado, says the variables that he faces daily on the road are hard for a machine to predict. He’s been driving trucks, on and off for 51 years, that’s 72 percent of his life.

“In this situation there are lives at stake with traffic around a self-driving truck,” Lake said. “I have a problem with all the variables you run into — accidents and weather — that the truck can react in time and the drivers can’t always do that either.”

One of the hardest difficulties for these trucks to overcome is visibility on the spectrum of white. Though Waymo, Embark and Otto trucks have omni-directional cameras, they have trouble determining if what’s in front of it is snow, fog or a white trailer, according to Lake, though they also use ultrasonic and radar to see object. A human would be much better at judging what visibility conditions are like.

Lake transports fuel around the Colorado foothills for Shell and used to transport jet fuel for the Montrose airport. He said it wouldn’t make sense for him to ever consider buying a self driving truck to add to his small fleet of two. Most of the driving he and his son do are off the interstate, between Montrose and Grand Junction, about 65 miles one way. Conditions on those roads harder to predict.

Trucking jobs, though at risk like they have never been before, will still exist for a very long period of time. Regional trucking is still important; artificial intelligence would have trouble keeping up with a combined 70 years of driving experience in Lake’s company. In their promotional video, Otto still has truckers taking over once the truck gets off of the interstate, and many current drivers think that it will be human and machine working together.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nfwOVvjK-sc&feature=youtu.be

But those who are employed in large trucking companies, contracted out by even larger multinational corporations, are the ones who can lose as they look to replace more people with automation to keep costs low. Keeping costs low will translate to lower prices in the store for consumers, but at the expense of a large portion of the population being unemployed and failing to reach their productive capacity.

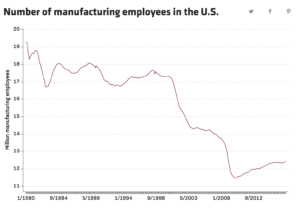

Manufacturing jobs are an important point of comparison as they were the first sector to make use of automation. The first automation technology was installed by General Motors in their factory in 1961. Since the 1980s, the manufacturing sector has lost a lot of jobs. It went from around 19 million to its lowest point at 11 and a half million in 2010, likely in part due to the Great Recession.

Even more, a study by the National bureau of Economic Research, showed that one robot per 1,000 people could reduce the employment to population ratio by as much as 0.34 percentage points and reduce wages by as much as 0.5 percent. The graph above still shows a resurgence in jobs, but it will likely never go back to that 20 million number.

For trucking, it illustrates that while automation could cause job loss, humans are still needed in some capacity to fix things when they break down and monitor them for safety. Automation may even reduce the sleep-deprivation that many truckers have by allowing them to sleep more on straight stretches of road without having to stop.

There’s still many obstacles these companies need to overcome before they can put these machines on the road. That includes the people that drive trucks as they will likely get in the way of any legislation that would legalize self-driving trucks with their livelihoods on the line. So for now, truck drivers will not face drastic unemployment, and may not for a long time because the human element can react better than any robot can. They could be on the road in three years or longer than 10 — it’s almost impossible to predict.

Lake still doesn’t see any benefits from automating trucking because for him it wouldn’t accomplish much.

“I don’t think it’s a good idea period to even be developing these trucks” he said. “I don’t even know what the advantage is or what they are trying to accomplish other than the fact that they can do it. Then you’re taking jobs away from people in America.”