In the aftermath of California’s most deadly wildfire season, in which 88 people were killed and over 18,000 structures destroyed, tens of thousands of displaced residents looking to return and rebuild are faced with yet another costly obstacle: a severe construction labor shortage.

In Butte County, where the deadly Camp Fire had decimated nearly 14,000 homes (around 18% of total homes built on an average year in California), the shortage could exacerbate the already tight housing market.

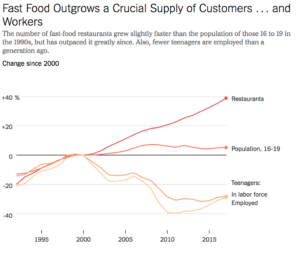

“Nobody’s gone into construction as a career for twenty to thirty years,” said Kate Leyden, executive director of the Chico Builders Association. “So we had a problem to begin with. We didn’t have workers and we had a very tight housing market even in Butte County.”

Leyden said that the labor shortage is pervasive all through Northern California and that builders often have to bring in workers from other counties to come in to work. But this then leaves a shortage of workers in the county of origin.

“Even if they come from Sacramento, that hurts Sacramento. In our area, we have these circles of fires—Santa Rosa, then Redding, and now Paradise—with each one of them, like with Santa Rosa, we see our trades go to Santa Rosa,” said Leyden. “To the north of us—Redding lost a thousand homes in July— we were concerned that we’d lose our trades to Redding, but they’re still cleaning up lots.”

In addition, around 1500 of the construction workforce in Butte County lost their homes, over a third of the 4500 workers the county had to begin with, according to Leyden.

Scott Littlehale, a senior research-analyst for the Northern California Carpenters Regional Council, said that much of the labor shortages are occurring in the residential construction labor pool, as opposed to the non-residential pool.

According to Littlehale, for decades residential developers have been relying on cheaper, more “unskilled” labor, as opposed to the more unionized laborer force in non-residential construction.

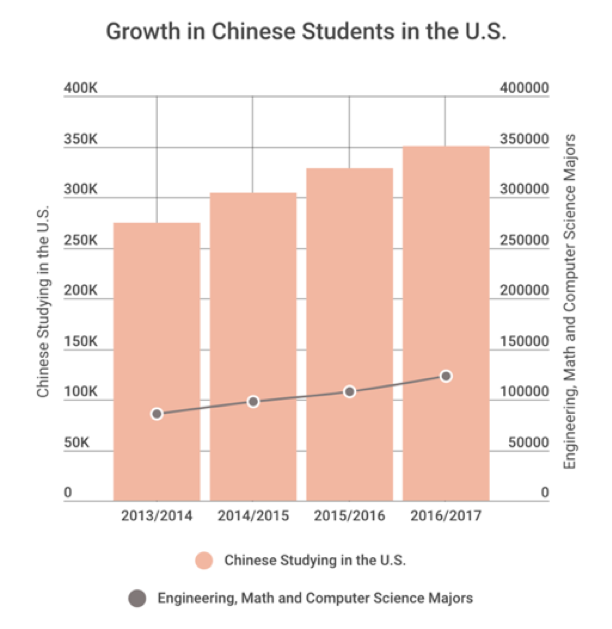

“The residential construction labor market was heavily influenced by immigration. It became a critical element. And immigration flows are way down.” Littlehale said.

“I think what the fires do is reveal that the residential industry has come to a dead end with a kind of ad-hoc, low road workforce strategy of relying on the cheapest labor that builders can find.”

He also cites the uneven keel of power between laborers and developers as another major factor, which have been driving down wages.

“It used to be that housing builders negotiated over terms and conditions with the unions. That has for the most part not been the case for decades because they left the collective bargaining table,” said Littlehale.

Low wages combined with the high injury rate in construction, he said, are the reason why many of the local young are discouraged about entering into the trade. You either take less pay and risk falling through a hole or roof or go into less stressful work.

According to Peter Phillips, a labor economist from the University of Utah, in more rural regions like Butte County, even raising wages won’t always guarantee a burgeoning construction labor force.

“Even if contractors do raise wages, that doesn’t necessarily bring new workers into the labor market if the labor market is isolated, such as rural labor markets around Northern California like Chico and Paradise,” said Phillips. “All construction is local. In places like Chico and Paradise, the construction industry has evolved to fit the size of that community. So there’s a hand-in-glove element where the construction industry comes to fit the size of the local community.”

For those on limited incomes, the costs to rebuild will be close to impossible to afford, especially for the uninsured and underinsured.

“We’ve been in Samona County after the North Bay fires in October in 2017 and when we surveyed the people we worked with six months after the fire, 66 percent of them were underinsured by some amount,” said Sandra Watts, project coordinator for United Policy Holders, a non-profit insurance consumer advocacy group. “Because of the location of Paradise, we anticipate it’s going to be quite a bit worse because there’s already fewer resources up there,” she said.

“We have something like 300 houses on the market for sale (before the fires). Now there are 61. Thirty of them were over a million dollars,” said Leyden. “So the people who could buy houses fast, bought houses right away. Then, the apartments got snapped up.”

With FEMA coming into Butte County to bring temporary trailer homes for displaced families, the first major step will be in the lengthy cleanup process that is to come.

“There’s never been anything like this. We’re sort of making it up as we go along,” said Leyden. “When this fire broke out, Chico Builders Associaton called an emergency meeting on how we can keep our construction labor force. The last thing we want is to lose what little workers we have.”