Sheila Li is a graduate student at the University of Southern California. After a year of job-hunting, she received an offer for a full-time job as a software engineer in Austin, Texas. The email came in at 1 p.m., but Li waited five hours– until the sun rose in Beijing– before she called her parents to announce the news. She knew they would be disappointed.

“My parents do not want me to work in the United Sates,” Li said, explaining that her parents hoped she would move to her hometown, Hangzhou, a rising tech hub that incubated both the multi-national e-commerce conglomerate Alibaba and the internet tech company NetEase.

It doesn’t help that Li, 21, like many of her generation, is an only child. Being a woman makes things even harder. “Parents never want girls to go far away,” she said, “but working as a coder in China is exhausting. Plus, I get higher salaries here.”

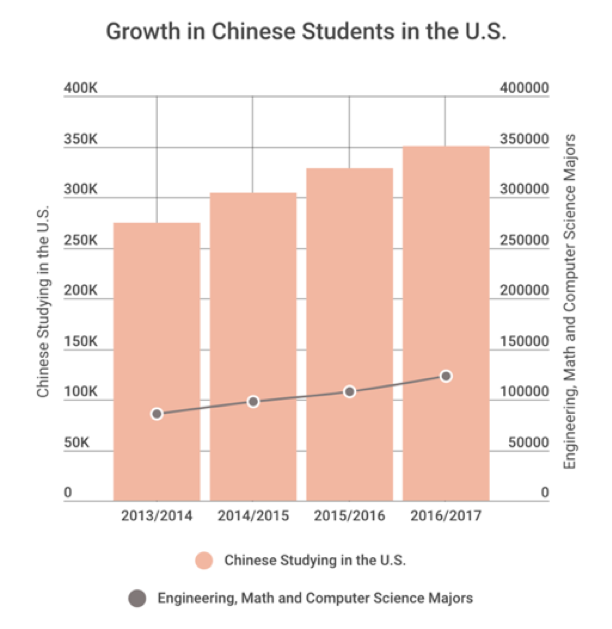

More than 350,000 Chinese students are currently enrolled at U.S. colleges and universities. A third of them are here to become engineers. A Chinese research firm reported this year that engineering grads received the highest-paying jobs in China, but many aspiring Chinese engineers who are studying abroad are nonetheless determined not to go back home.

Dr. Danny Friedmann is a law professor at Peking University. He explained that there is a gap between the economic growth and a dearth in skilled coders, thus Chinese tech workers receive lower payment than those in the U.S.

“The higher salaries and better working conditions for coders, the higher costs for the companies, which makes them less competitive in the short term,” he said.

A Choice of Lifestyle

Apart from the payment, the reasons may be linked to a relentless work culture. Chinese tech companies have reportedly been pushing their employees to work overtime, encouraging employees to compete to work the longest hours. The companies accommodate this approach with o do this, they offer late meals, night shuttles, and even bunk beds in the office.

Fuzhi Wang is a hardware engineer at Huawei, a Chinese telecommunication equipment company based in Shenzhen. He said that he and most of his colleagues work “9-9-6” — from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week. “The company does not mandate long working hours,” he said. “But people simply won’t leave the office at 5 o’clock.”

In August, Huawei passed Apple to become the world’s second-largest maker of smartphones, Bloomberg reported. In 2017, the company invested approximately $13 million, which accounts for about 15 percent of its revenue, in research and product development. Forty-five percent of its workforce are involved in R&D.

This means Huawei’s demand for tech workers is enormous. “Huawei is catching up with the U.S companies, said Yiwei Song, who worked as recruiting coordinator for Huawei in 2017. “It prefers to recruit students that have studied abroad and expects them to bring back fresh ideas.” Students with overseas educations tend to benefit from high salaries and greater opportunities for advancement than those who graduated from domestic universities, she added.

Despite the preferential treatment they receive back home, new grads from China tend to choose Silicon Valley over Shenzhen.

Sheila Li believes there is a bigger backstory — China lacks proper intellectual property protection for tech companies.

“Once company A creates something, company B would steal the idea, which pushes company A to accelerate the process of innovation,” she said. “There are distorted competitions in the market. As a result, engineers have to work day and night to catch up with that speed.”

Dr. Friedmann said China does have a proper intellectual property law system in place in the books, but on the ground, this is not always manifested, for example, because of local protectionism.

“Intellectual property in general is sometimes ill-equipped to protect these fastly developing innovations,” he said, “and in the case of software the copyright protection, it seems too long as well.”

After receiving his master’s degree from the New York University, Zhi Cao went back to Wuhan, the capital city of his home province, to work for a tech start-up.

“I am considering applying for another master’s program in the U.S.,” he said. “Life here (in China) is too intense and I don’t think I could adapt to it.”

Cao had been in the U.S. for six years before he went back to China, since he went to undergrad in New York as well. “I really regret that I didn’t stay in the States,” he said.

Yi Leng just received his master’s degree in engineering from the United States and landed a job at Amazon. “Here everything is based solely on merits,” he said, adding that interpersonal relationships between colleagues were “simpler” in the U.S, while the “guanxi” culture in China, where everything is based on networking, added complexity to the working environment.

Leng has a green card, but he is not obsessed with the idea of living in the U.S. “If I get to play my role and contribute to my own country with what I’ve learned here, I will go back,” he said.

The Challenges to Stay

Unlike Leng, most of international students who intend to work in the U.S. here need an H1B visa. It is a type of non-immigrant visa for international students to work in the United States.

According to MyVisaJob, Facebook, LinkedIn, Amazon, Apple and Google filed 13,875 Labor Condition Applications (LCA) for H1B Visa in fiscal year 2017. A year before that, the number was 11,047. The trend resulted from STEM-favored policies under the Obama administration as well as rapid expansions of tech giants in the United States. For years, Silicon Valley has been demanding skilled foreign workers, especially in the tech niche.

“I can imagine the day when a large portion of tech workers will be coming from Ohio and Michigan,” said Professor Dowell Myers, Director of the Population Dynamics Research Group at the University of Southern California. “I can imagine that day, but it’s impossible.”

Myers said the United States has a shortage of workers, shortage of all levels — blue collar, white collar and scientists’ levels. As a result, Chinese and Indian engineers become “important shares of the technology workers”, he said, and added that they can be influenced by the recent immigration policy.

President Trump’s Buy American and Hire American Executive order gives creates more barriers for H1B petitions to be approved. This disincentivizes companies to sponsor new grads. The number of petitions the immigration department received in 2018 has drastically decreased from 236,000 in 2016 to 190,098, according to its website. That means employers have shrunk their quotas for international employees.

Notably, Amazon this year earlier began a round of corporate layoffs. Back in 2016, the company sent out a huge amount of job offers. At that time, applicants were only required to complete two online assessments before they got recruited. Now, it takes multiple rounds of interviews for an applicant to proceed into the final phase of recruiting.

Amazon is also locating its second headquarters in East Coast. Myers suggested such locations, as opposed to the West Coast, is centered in an area with a higher percentage of this was to give more jobs to native-born Americans than immigrants in the job pool.

Despite the shift in political climate, the number of Chinese students coming to the United States for higher education is increasing. Engineering remains the most popular major for them. The field of math & computer science witnessed a drastic increase of 18 percent in its student population of all origins from 2016 to 2017, according to the Institute of International Education.

“Even if tech companies do not reduce the number of positions for foreigners,” Li said, “more and more international students are flowing into this industry with a hope to secure a job here, the competition of job-hunting in the States would only be fiercer year after year.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.