Motor vehicles have become a major part of the U.S. economy since its creation. They continue to rule the streets of the U.S. in the forms of cars, trucks, and buses. Although it has become such an integral part of our daily lives, the total sales of motor vehicles are the key to predicting the future of the U.S. economy.

In the last 29 years, the U.S. economy has gone through tremendous ups and downs. The lowest the economy has fallen in the last 29 years was from 2007 to 2009. This period is known as the Great Recession. During the Great Recession, the unemployment rate doubled from 5% to 10%, about 3M households were foreclosed on from 2005 to 2009, and the GDP in the U.S. declined by 4.3%. For those living in the U.S. during this time, it became clear that there was something very wrong with the economy.

To indicate how the economy is transforming through any time, economists may analyze the Gross Domestic Product, the Consumer Price Index, or the interest rate. However, an economic indicator that may not seem as apparent as the GDP, for example, is the total motor vehicle sales in the U.S.

According to Julia Kagan at Investopedia, the total motor vehicle sales is “the number of domestically produced units of cars, SUVs, mini-vans and light trucks that are sold.” The total number of motor vehicle sales in the U.S. is measured by the reported sales by individual manufacturers on the first business day of every month. Although one may categorize the sale of motor vehicles as a part of consumer spending in general, motor vehicles play such an integral role in our society that it may act as an economic indicator.

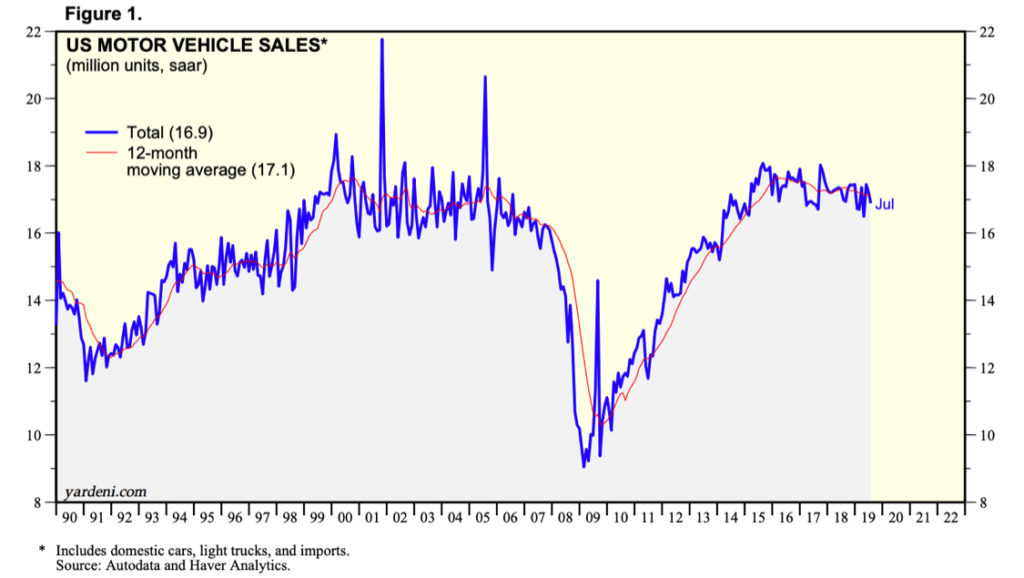

In Figure 1, it is clear that leading up to the Great Recession, the total vehicle sales in the U.S. was steadily positive from the period of 1991 to the middle of 2007. Then, the Great Recession occurred, and all motor vehicle sales dropped significantly until the beginning of 2009. Although there are various factors associated with this significant drop, it is important to note that, during this time, the Big Three automakers in the U.S. had to ask Congress for help similar to the bank bailout. At that point, General Motors Company and Chrysler LLC faced bankruptcy, and the Ford Motor Company needed help to compete with other automakers. Eventually, sales began to rise and have now started falling.

In 2019, the first-quarter auto sales have dropped by nearly 2.5% from the previous year, according to J.D. Power and LMC Automotive. This is due to auto manufacturers producing more expensive cars rather than cheaper cars, which helps the used car industry but hurts the new vehicle market. However, it is important to also think about the demand for new cars. The demand for new cars may be decreasing due to various economic factors that relate to consumer confidence. Therefore, the total motor vehicle sales in the U.S. acts as an economic indicator that is telling of the future of the U.S. economy.

Sources

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/motor_vehicle_sales.asp

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/03/26/us-auto-sales-are-falling-and-cars-are-more-expensive-than-ever.html(J.D. Power and LMC Automotive)

https://www.yardeni.com/pub/ecoindauto.pdf(Figure 1)

https://www.thestreet.com/politics/what-was-the-great-recession-14664025(Statistics: The Great Recession in Numbers)

https://www.history.com/topics/21st-century/great-recession-timeline

https://www.thebalance.com/auto-industry-bailout-gm-ford-chrysler-3305670