On Wednesday, March 27th, the Chicago district of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruled that Northwestern players, led by former Northwestern Quarterback Kain Colter, qualify as employees of the university and can unionize. The decision, at first glance, might seem like a big win for collegiate athletes and their battle for compensation. But unionizing collegiate athletics is layered with multiple issues ranging from the differences between private and public institutions, tax issues and vast economic implications.

Jay Bilas, an ESPN College Basketball analyst, former Duke basketball player and lawyer argues that the NLRB’s decision won’t affect anything in the short term, as the decision of whether collegiate athletes can unionize will, ultimately, end up in federal courts if it’s able to pass the national NLRB. But scandal has surrounded the NCAA since its formation more than a century ago, and now, more than ever, athletes, administrators and fans sense a momentum of change.

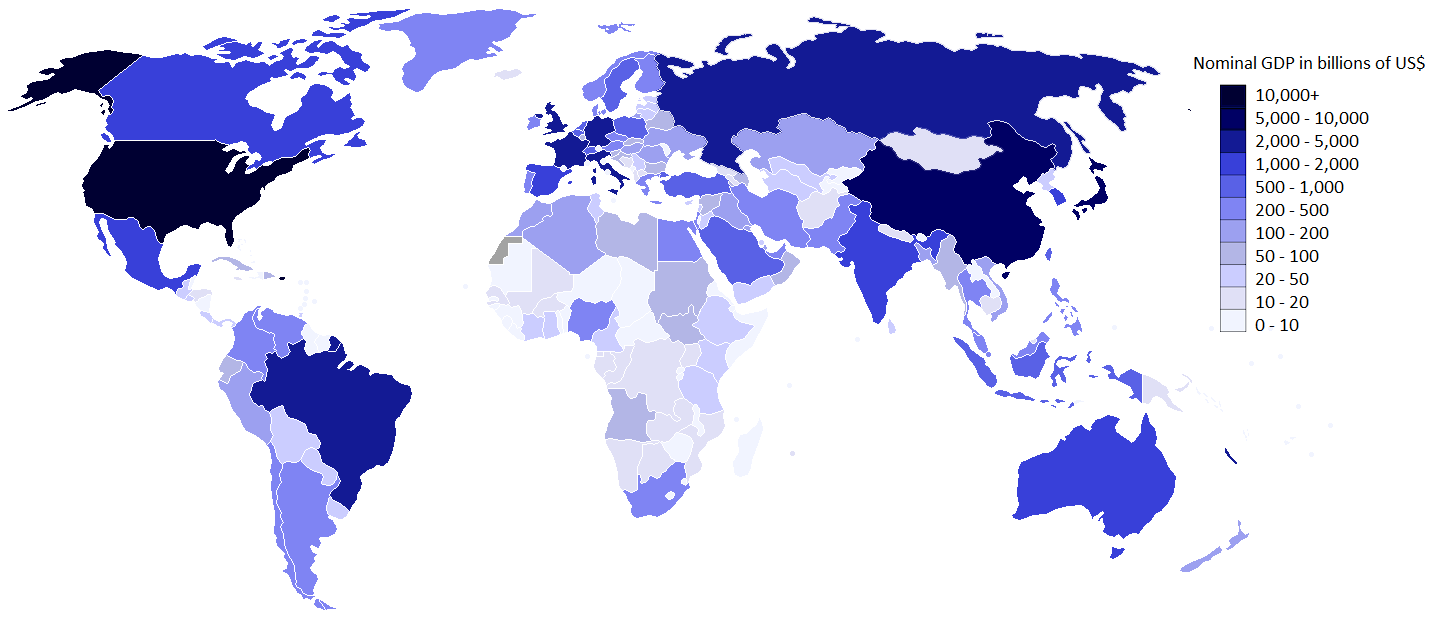

In 2013, the NCAA March Madness Tournament brought in more than $1.1 billion in television advertising revenue, $55 million more than the NFL Playoffs and $223 million more than the NBA Playoffs, according to ESPN. Student-athletes do not recoup any of that revenue, besides an athletic scholarship that ranges between $5,000-$65,000 per year. In 2008, the athletic programs at Alabama, Texas, Ohio State, Florida and Tennessee each made more than $100 million in total revenue. Alabama’s Head Football Coach, Nick Saban, is the highest paid public employee in the State of Alabama and makes at least $7 million per year, which is more than the salaries of all the head football coaches in the Mid-American Conference combined.

The NCAA argues that amateurism and money are mutually exclusive. But collegiate athletes, especially in sports that turn a profit, such as football and men’s basketball, continue to challenge that notion. However, the NLRB decision could have unexpected tax implications and throttle the momentum. The motion put forth by Northwestern players and their lawyers argued that athletes received compensation in the form of a scholarship making them employees of the university. If the scholarship were deemed as taxable income in federal courts, an athlete would have to pay at least $15,000 in federal taxes on a $61,000 per year scholarship. In addition, this particular ruling only serves private universities, because the NLRB does not govern labor matters at public institutions. A majority of the top performing Division I collegiate athletic programs are public universities, including all five of the universities that exceeded $100 million in total revenue in 2008.

If collegiate athletes were ever able to unionize, the NCAA would deem them ineligible for receiving compensation for play. And the NCAA has always been happy with taking the easy way out and promoting inertia. But the answer to paying collegiate athletes is simple and not as convoluted as the NCAA makes it seem. To pay athletes, universities could utilize a free-market approach, as it’s worked well for the rest of us. Like any other contract, the player and university could negotiate terms, require a player to stay for three or four years, introduce non-compete and behavioral clauses and detail a performance clause that highlights performance goals on the football field or basketball court and in the classroom. Smart minds can dictate how change can be effective and efficient and satisfy the needs of all parties involved, but asking fat cats to stop eating and make room at the dinner table, might be a little harder.

Sources: ESPN, NPR, SBNATION, ESPN