November 2019 marks the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. From 1961 to 1989, the Berlin Wall separated West Berlin from East Berlin. Standing approximately 12 feet high and 27 miles long, one of the reasons the Wall was created was to keep East Germans from fleeing to the west.

The fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989 meant that East Germans were free to travel and to work outside of their country for the first time in decades. A New York Times article written three days before the Wall fell about the economic impact the fall could have on Europe mentions that “since East Germans can automatically obtain citizenship in West Germany, they also become citizens of the European Community, free to travel and seek jobs, housing, and eventually welfare benefits in any of the other 11 member countries.”

Within a year of the fall of the wall, East Germany and West Germany reunited into one whole Germany. That new Germany was generally economically stable with a stable currency. The European Community morphed into the European Union, which Germany is heavily associated with. The country’s general economic strength typically means that the European Central Bank’s “one size fits all” interest rates only fit Germany.

A Pew Research Center study found that while Germany is generally viewed positively in Europe, views of Germany are tied to the EU as a whole. Essentially, if you like the EU, you generally like Germany. Since the global financial crisis, that’s less likely to be the case. In Italy, unfavorable views of Germany increased by 27 percentage points between 2007 and 2017.

But Greece is where the real hate is at, with a little over three-quarters of Greeks having an unfavorable view of their fellow EU member. “The country is several years into an austerity program imposed by the EU and backed by Merkel’s government,” the study reminds.

There’s another group of people that aren’t too fond of Germany right now: the Germans. More specifically, people from the eastern German states. It’s been 30 years since the Berlin Wall and 29 years since the German Reunification, and they are still living with the consequences. According to Marketplace, many state-owned companies were sold off to the private sector post-unification and many others collapsed because they could not compete in a market economy.

When the Berlin Wall fell, many things changed for the better – residents of East Germany could see loved ones on the other side of the border again, could participate in democratic elections, and could travel freely. The economics of the matter is different. It has fostered a feeling of discontent amongst the former East Germans, who say they feel like they have been treated like second class citizens.

According to a recent opinion poll, only 38 percent of Easterners regard the unification as a success – perhaps due to the feeling that it was not a reunification of two Germany’s but the absorption of the East into the West. Jörg Roesler, an economist, said that although western taxpayers spent $2 trillion to improve infrastructure and a social safety net in the former East Germany, it was wasted. Roesler believes what Eastern companies needed was protection. He told Marketplace that if they had been protected for up to five years, a generation would not have been unemployed and “made to feel worthless.”

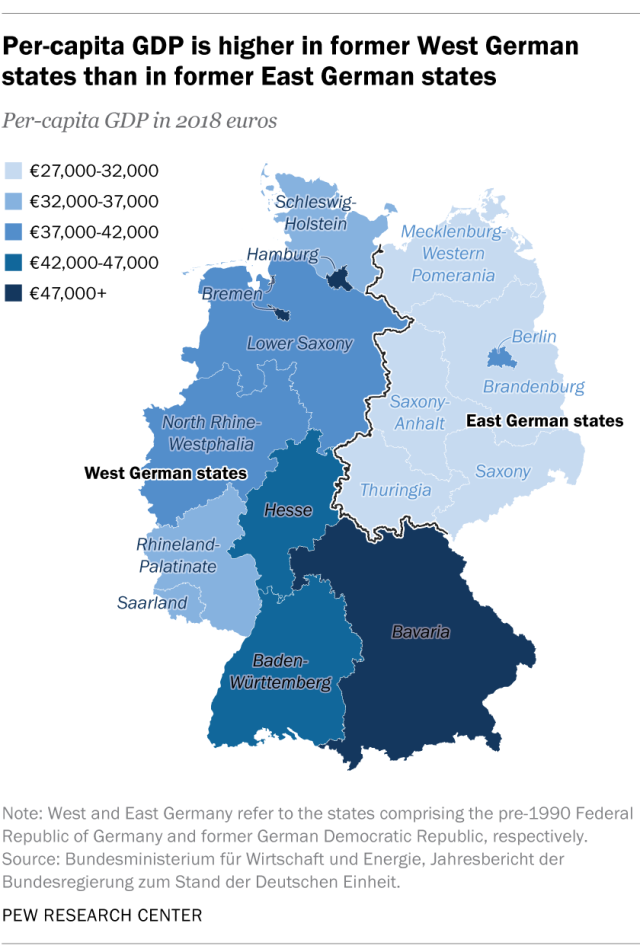

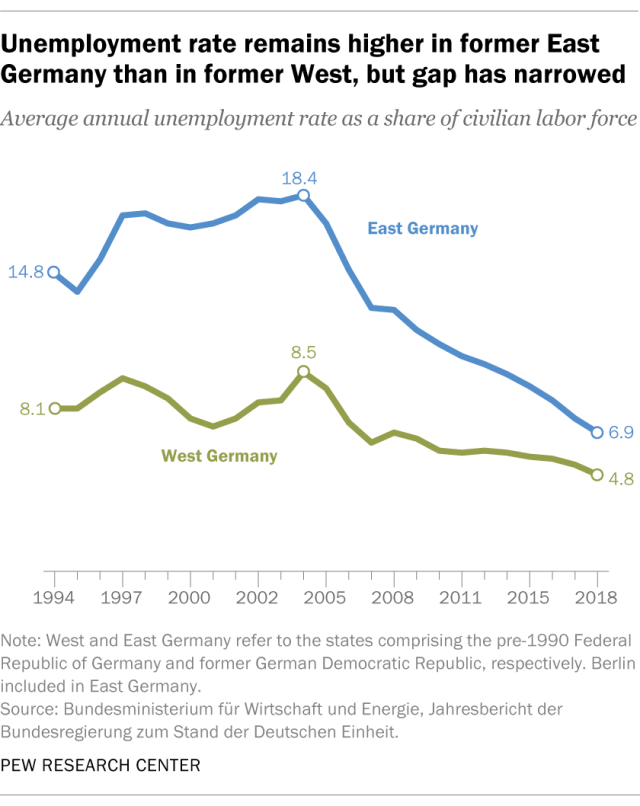

The dissatisfaction of the former East Germans isn’t just resentment over something that happened 30 years ago. Eastern Germans are still being effected. A Pew Research Center study on how the economic conditions of East and West Germany changed over time found that unemployment in the former East Germany is higher than in the former West Germany by around 2 percent. Although the economic gap between the two regions has become narrower recently, former East Germans make less money than former West Germans.

“People in the former East Germany earned 86% the after-tax income of their West German counterparts in 2017,” said the study. “That percentage has changed little in recent years, but is far higher than in 1991, when per-capita disposable income in the former East was only 61% of that in the former West.”

The physical Berlin Wall may have fallen 30 years ago, but its economic and psychological shadows live on.

SOURCES

- https://www.cnn.com/2013/09/15/world/europe/berlin-wall-fast-facts/index.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/1989/11/06/world/as-berlin-wall-totters-symbolically-europeans-brace-for-economic-impact.html

- https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2017/06/15/favorable-views-of-germany-dont-erase-concerns-about-its-influence-within-eu/

- https://www.marketplace.org/2019/11/08/berlin-wall-economic-aftermath-affects-east-germany/

- https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/06/east-germany-has-narrowed-economic-gap-with-west-germany-since-fall-of-communism-but-still-lags/