Pumpjacks hammer for petroleum in Moinesti. They hammer and hammer and hammer like it’s still the 1970s, when the government-run petroleum industry kept the small municipality economically afloat. Then, Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu was overthrown in 1989 with a bloody revolution that ended with him and his wife getting executed on national television, on Christmas Day.

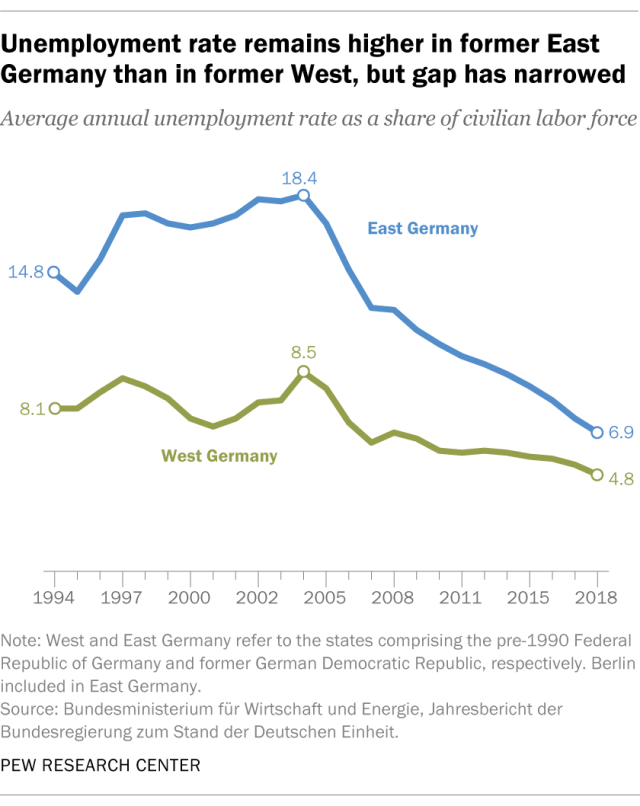

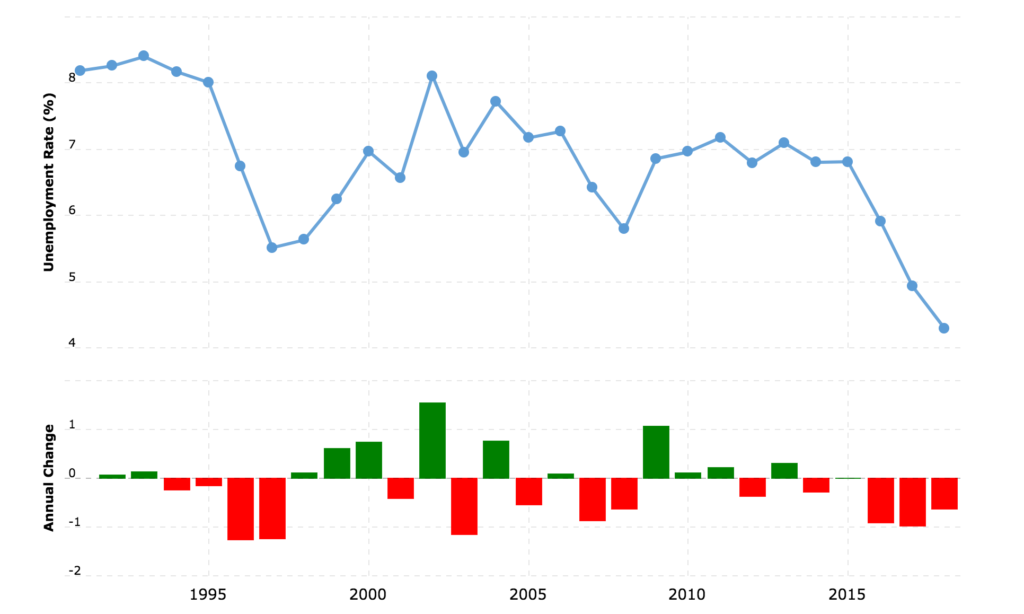

As Romania shifted from communism to capitalism in the 90s, the petroleum industry was privatized, and life in Moinesti changed as petroleum jobs fled the community. At its worst, the municipality’s unemployment rate was more than 20%. In 1993, Romania’s unemployment rate was 8.40%.

At first glance, Moinesti looks unremarkable. Almost 200 miles away from Bucharest, Romania’s capital, Moinesti is surrounded by farmland and clusters of small villages. With a population of roughly 20,000, it is not uncommon to see horse-driven carts on the street. It is also located in Moldova, Romania’s poorest province and the fifth poorest region in the European Union.

Still economically recovering from the loss of petroleum industry, Moinesti is known for four things: 1) Being a “global village” destination for Habitat for Humanity, 2) having a Jewish cemetery, 3) the fact that a giant DADA mural marks the entrance to town, and 4) having surprisingly good health care.

There are two major medical facilities in Moinesti: a private clinic and a public hospital. The private clinic, MALP Moinesti, is run by Dr. Mihaela Cotirlet and provides various types of care, including family medicine, infectious diseases, rheumatology, nephrology and clinical psychology.

Her husband, Adrian, runs the public Moinesti Municipal Emergency Hospital; he was voted the best healthcare and pharmacy manager in 2019 by Capital, a business and economics magazine. His hospital is working on new infrastructure projects to improve the hospital’s accessibility to neighboring counties and extend hospital spaces, bringing some jobs to Moinesti.

Good healthcare is something of an oxymoron for Romanians due to the system’s infamous corruption. After the fall of the dictatorship in 1989, the healthcare industry, much like the petroleum industry, switched from government-owned to privately owned.

“We found ourselves in a system in which the disrespect placed its influence on the young doctors, a system that had not developed any strategy for the doctors who wanted more than the state of employment,” Cotirlet said.

According to a study by Mihaela Cristina Dragoi, a professor at the Bucharest Academy of Economic Study, the political changes in 1989 created a partial replica of the totalitarian regime’s sanitary system: the Semashko system. Borrowed from the Soviet Union, the Semashko system’s goal was to provide free, universal healthcare through a multi-tiered system of differentiated networks of service providers.

Romanian physicians lobbied for reform, to change from the Soviet Semashko model to the German Bismark model, which provides free, universal healthcare through an insurance system jointly financed by employers and employees. According to Dragoi, reform was stunted because of Romania’s political instability.

“Frequent changes of government and ministers, the lack of clear strategy and defined objectives to be pursued rigorously and independently of political changes slowed down the health reform process after 1990,” she wrote.

Bribery is common in the sector, and since 2007, the EU has invested over €12 million to fight against corruption in Romania. Even though Romania provides universal healthcare, the system does not provide equal coverage; rural areas are frequently left behind.

In short, a combination of Soviet bureaucracy and crony capitalism has led to Romania’s health care sector turning a transaction of care into an economic exchange.

Perhaps no event in recent Romanian history encapsulates the crony capitalism that has infiltrated the system as much as the 2015 Colectiv nightclub fire, which claimed the lives of 64 people. While 27 of those people died on the scene, the other 33 passed away in the hospital, some from preventable bacterial infections. Gazeta Sporturilor (“The Sports Gazette”), a daily Romanian sports newspaper, investigated, and found that government health authorities never inspected the disinfectant used by hospital staff.

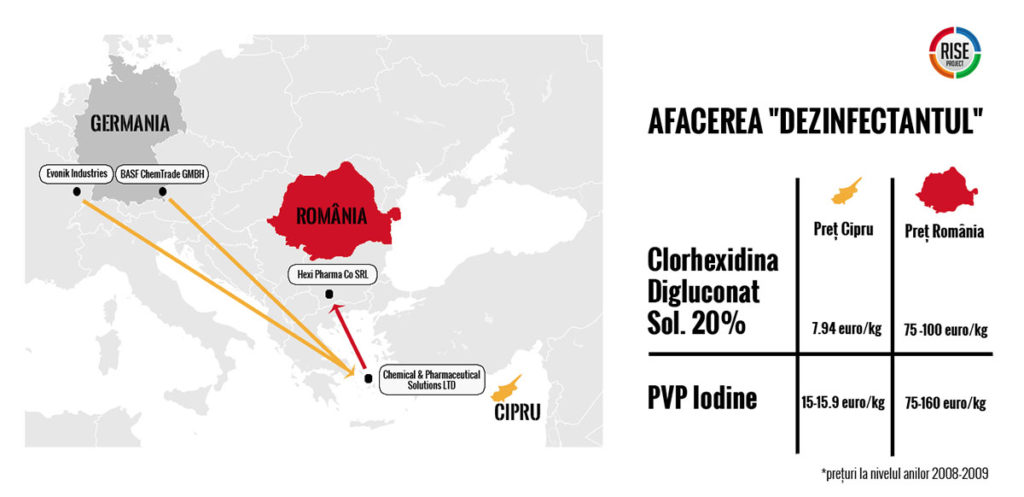

The quality control came from Hexi Pharma, a pharmaceutical company who distributed antiseptics to 350 out of 367 public hospitals in Romania. Further investigation revealed that Hexi Pharma diluted the disinfectants to increase profits. In addition, hospital directors allegedly took a 30% cut on Hexi Pharma contract. According to the RISE Project, a non-profit journalism organization based in Romania, Aurelian Condrea, the owner of Hexi Pharma, would buy a liter of disinfectant from Germany for about €7.9 euros, sent to offshore mediary Condrea owned in Cyprus, and then finally sold in Romania for €75 – €100.

Public outrage over the Hexi Pharma scandal and Colectiv nightclub fire deaths led to the resignations of multiple cabinet members, including Prime Minister Victor Ponta and Patriciu Achimas-Cadariu, the Minister of Health. Achimas-Cadariu’s replacement was Vlad Voiculescu, an economist with no prior political experience, known for creating the Cytostatic Network, a group of volunteers who bring cancer drugs free of charge to Romania from other countries.

This is the kind of system Dr. Mihaela Cotirlet is operating in. “For some, [a doctor] is just a person. For others, it’s a white coat,” she said. “And for the system, it’s an investment.”

Although Romania’s healthcare system struggles with corruption and inefficiencies, Cotirlet tries to operate her practice with a simple maxim: Be the change you wish to see in the world.

One thing she is trying to change is the level of access to healthcare in rural areas, a historic problem in Romania’s universal healthcare system. Her clinic is the only clinic in the Moinesti municipality; without it, villagers from neighboring communes like Poduri and Solont would need to drive approximately 30 miles to Bacau, the county’s capital, in order to receive care.

Although her practice is well-established, renowned in Romania and financially stable, the Moinesti native said she remembers her experience with medical school in Ceausescu’s Romania vividly. “You deliver babies, clean them in pots, and as transportation, you have to use a carriage pulled by horses,” she said.

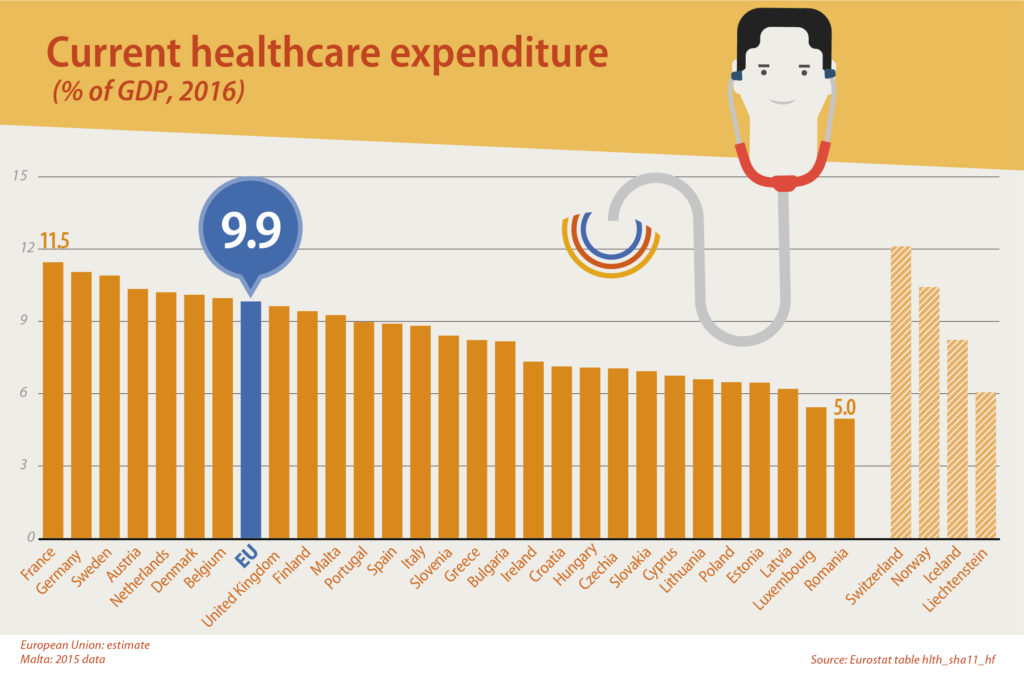

Romania’s healthcare system is still underfunded today. In fact, Romania spends the least of its GDP on healthcare out of all EU countries. In 2016, that meant that only 5% of the total GDP went to the public health system. According to Cotirlet, it’s this sort of environment that has made Romanian doctors tough.

“They [Romanian doctors] are used to hardship, with hospitals with no medical equipment,” she said. “For that reason, they are very good clinicians. Management counts: even with less money, people can achieve progress.”

However, until 2018, many Romanian medical practitioners weren’t paid as though they were valuable members of society. In 2015, a first-year resident physician in Romania made €260 (~$288.30) a month. Meanwhile, in the United States, the 2015 Residents Salary & Debt Report found that the average yearly salary for a first-year resident was $52,000, or roughly $4,333.33 a month. That is around 15 times more than what a first-year Romanian resident would make.

The economics of this made living self-sufficiently as a doctor difficult, if not impossible, leading to a brain drain. From 2009 to 2015, half of Romania’s doctors left the country, leaving almost one-third of hospital positions vacant. Despite Romania being a leading EU state in medical school graduates, the Ministry of Health estimates that one in four Romanians have insufficient access to essential healthcare, which makes practices like Dr. Mihaela Cotirlet’s all the more necessary.

Sometimes, it can feel like there is no incentive for people to stay. That goes beyond just doctors. According to the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, conservative estimates put one in five working-age Romanians living abroad. Romania has the second-fastest growing diaspora, only after Syria.

But Dr. Alexandra Scovronschi, also a Moinesti native, decided to move back home after completing dentistry school not only to start a family with her husband, a surgeon at a public hospital, but to start her own private dental practice.

According to residents of Moinesti, Scovronschi’s dental practice is one of the first in Moinesti that has been accessible to locals. Because Moinesti was a small town where Scovronschi grew up, some parts of starting a business were simpler because she knew the people and the people knew her. It made it easier for her to build a client base.

Scovronschi remembers the pumpjacks digging for petroleum as that segment in Moinesti’s economy began faltering. It was the same year she had a health scare and underwent surgery at the public hospital in Moinesti, which has received national prestige for its hygienic conditions.

Scovronschi said she knew she wanted to be a doctor since she was a little girl, but didn’t realize how badly she wanted it until she decided to go to college for economics instead of pursuing medicine.

Unlike in many other Western countries, a career in medicine did not equate to wealth. During her summer holidays from business school, Scovronschi said she worked at a small tile business in Southern California where she made around $1,600 a month – more than five times what she would have made as a first-year medical school resident.

In 2018, the government raised the base gross salaries for public health employees by more than double in order to stem the hemorrhage of medical professionals. First-year residents will now earn €715 ($792.85) a month. Whether this succeeds in stopping the brain drain is yet to be seen. This move is also intended to help stop the common practice of bribing medical professionals for better care.

“Receiving flowers, boxes of chocolate, and coffee is not bribing. It’s a form of showing respect and appreciation after the work with the patient,” Cotirlet said. “This is rooted in customs, but what is condemnable are the ones who ‘ask something’ because now the salaries are sufficient.”

Many of the municipality’s Gen Z population decided to pursue medicine in college. Raluca is a Moinesti native who is on her first of six years of medical school at the Iuliu Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj-Napoca, generally abbreviated as UMF Cluj. She has requested that her surname be withheld.

According to Raluca, out of the 30 students she graduated high school with, 15 wanted to go to medical school. Eight got into a medical college in Romania, four reapplied and got in the following year, and five decide to change their path.

Cluj, the fourth most populous city in Romania, can sometimes feel like a whole world away from Moinesti. “In Moinesti, it’s impossible to go outside and not bump into someone you know. In Cluj, you can walk for three hours and not find someone you know,” she said. “I don’t plan on going back to Moinesti.”

Although she was born around the time the petrol industry left Romania, she said she remembers the pumpjacks hammering for oil even though all the jobs left the community, sending them into a downhill economic spiral. “Bad men got rich backs on the backs of the people,” she said.

Growing up in a Romania defined by corruption and scandal can make it hard to not become at least a little cynical, especially for an aspiring doctor.

“At a certain moment, you need to have hope. And then you meet people who have no hope for the future, and that affects you,” she said. Becoming a doctor is a life-long ambition, and she said that she can’t picture herself being happy doing anything else, but to find happiness in her career, she might have to leave her country.

“It’s easier to leave than to stay and fight. So many people want to leave. So many people in my year want to leave,” she said.

According to her, this leaves Romania’s medical system in a tenuous state – without capital and with young people leaving, there are few people bringing in new ideas. “At the same time, there is nothing to offer them,” she said. “Either way, the school makes money.”

This system made her want to leave Romania for a long time. “Now, I don’t. The salaries are rising. And I still have five years to decide.”

Raluca said that although the system creates good doctors, it’s deeply flawed. For her, two of the largest problems are the underfunding and bribery. Growing up, she said there was pressure to bring mita, or bribes. “It’s ugly. I hope my generation stops accepting money,” she said. What makes mita particularly heinous to her now is that with the salary increases, it is unnecessary.

“I just want to live in a state where there is no political turmoil,” she said.

As a new generation is left to find hope and battling a fight or flight instinct, the pumpjacks of Moinesti still hammer.

SOURCES

- https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/dp5a3m/romania-hospitals-infection-health-minister-resignation-876

- https://www.tolo.ro/2016/04/25/statul-roman-nu-verifica-niciodata-in-laborator-dezinfectantii-din-spitale-retete-din-fabrica-celui-mai-mare-producator-arata-ca-antisepticele-sunt-diluate/

- https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/11/21/romanias-health-care-system-the-eus-worst-struggles-to-reform

- https://www.riseproject.ro/infectii-la-suprapret/

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/04/romanian-government-resigns-nightclub-fire-victor-ponta

- https://govnet.ro/Local/Politics/Vlad-Voiculescu-founder-of-the-Cytostatic-Network-in-Romania-appointed-Minister-of-Health

- http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/317240/Hit-Romania.pdf

- https://www.habitat.org/volunteer/travel-and-build/global-village/trips/gv20825

- http://librafoundation.org.uk/moinesti

- https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/ROU/romania/unemployment-rate

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227462920_CURRENT_ECONOMIC_AND_MEDICAL_REFORMS_IN_THE_ROMANIAN_HEALTH_CARE_SYSTEM

- https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/5/13-030513/en/

- http://www.annfammed.org/content/11/1/84.1.full

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269719141_Medical_Bribery_and_the_Ethics_of_Trust_The_Romanian_Case

- https://www.malp.ro/despre-noi/

- https://www.google.com/search?q=distance+between+moinesti+and+bacau&oq=distance+b&aqs=chrome.0.69i59l3j0j69i57j35i39j0l2.1736j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS

- https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/state/docs/chp_romania_english.pdf

- https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/public/residents-salary-and-debt-report-2015#page=4

- https://www.romania-insider.com/romanias-brain-drain-half-of-romanias-doctors-left-the-country-between-2009-and-2015

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/romanias-healthcare-exodus-a7634001.html

- https://www.romania-insider.com/romanian-doctors-teachers-salaries-go-today

- https://a1.ro/news/social/c-id934061.html

- https://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/articles_papers_reports/20190627-romanian-diaspora-impact-european-stability

- http://business-review.eu/news/romanias-regions-the-rich-get-richer-and-the-poor-stay-poor-eurostat-data-show-159959

- https://www.desteptarea.ro/premii-cercetare-dezvoltare-si-investitii-in-spitalul-municipal-de-urgenta-moinesti/