Known for its glaringly yellow shopping bags, paper-thin shirts and stores blasting bubblegum pop ballads, Forever 21 has marketed itself as a teenybopper retailer set on the rapid comings-and-goings of the fashion industry. At its peak only three years ago, the privately-owned, American fast-fashion company grossed $4.4 billion in annual sales, opened 800 stores globally and employed up to 43,000 people reported the New York Times.

Just last month, however, the retail giant announced it would be filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection meaning the business will still operate but will restructure its debt repayments to investors. The founders said they’d be stopping production with 40 companies, shuttering 178 stores within the United States and closing up to 350 total brick-and-mortar locations worldwide.

What became of the retailer which seemed to dominate every other mall and bring in hordes of teenagers and moms who wanted to preserve their inner 21-year-old?

Two words: retail apocalypse. The term refers to the advent of online shopping and shifting consumer habits that has caused many retail stores to close, forcing many companies to declare bankruptcy.

Starting in 2017, malls through the United States saw closures of prominent stores. Major stores such as Payless ShoeSource, Abercrombie & Fitch, American Apparel, Gap Inc., Charlotte Russe, J.C. Penney, Michael Kors, Bed Bath and Beyond, and Toys ‘R Us have been affected by the retail apocalypse. Alarmingly, this was during a time when the economy was strong and unemployment was low.

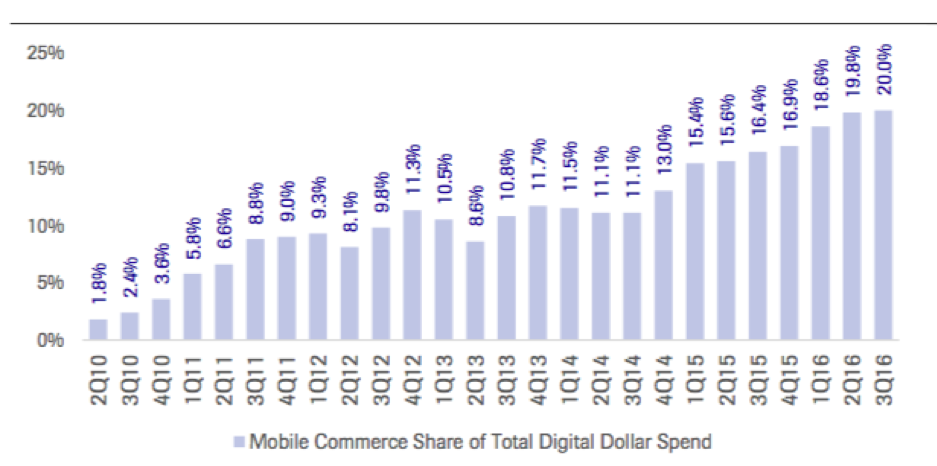

Both department stores and middle-tier mall chains either went out of business completely or shifted their focus to online distribution. The average household spent $5,200 online in 2018, a figure that rose almost 50 percent from 2013, as reported by the Washington Post.

Of U.S. retail stores, 75,000 out of approximately 1 million will close by 2026, according to the Washington Post, with online shopping making up nearly a quarter of sales. However, this figure isn’t as high as years prior. During the 2001 recession, 151,000 stores closed and again during the 2008 recession, another 148,000 stores closed.

For Forever 21, the combination of the retail apocalypse plus the owners’ reluctance to allow the privately-held business to be managed by others led to its eventual downfall.

In 2017, the Atlantic published an article describing three of the major contributors to the retail apocalypse: the rise of e-commerce, the number of malls in existence and the shift in consumer spending from retail to restaurant consumption.

Currently, there are about 1,100 shopping malls nationwide. During the late 1950s, many malls in America were built on the idea of a communal ground for middle-class, suburban America. As much as it was a workplace for minimum wage jobs, it was also a meeting ground for anyone and everyone to socialize. At one point, mall developers had dreams of a futuristic destination spot that housed apartment buildings, office space and hospitals. Its popularity fueled the construction of more and more malls. Nowadays, malls are less of a destination and are seen as a place to run errands or bypass shipping fees. Forever 21 occupied many malls with leases that were too long and spaces that were too large for the amount of merchandise they sold, fueling its demise.

On the consumer demand end, behaviors and attitudes toward stores like Forever 21 and its competitors like Zara and H&M have also changed.

For Sarah Okamoto, a USC junior majoring in computer science, a big portion of her money went to buying clothing, mainly from Forever 21. About once a week over the span of six years, Okamoto spent over 35 percent of her income at its brick-and-mortar stores.

“I started to realize it was almost [becoming] like single-use clothing, and I realized I didn’t want to be spending money on those things,” Okamoto said. “More and more people began pointing out that it was a fast-fashion brand, and it was really harmful for the environment. I think as people started to move away from that and there became more sustainable clothing options, I didn’t really feel a need to keep shopping there.”

In addition to consumers becoming more aware of the harmful environmental impacts of fast fashion, Okamoto cited the rise of minimalism, thrift shopping and cleaning guru Marie Kondo. These new trends may also affect what consumers want to see in-store now. Similarly, stores that sell similar items to Forever 21 such as Charlotte Russe and Claire’s have also filed for bankruptcy in recent years.

With the rise of other fast-fashion competitors who have made their success through social media marketing and online distribution, the question then remains if Forever 21 can pick themselves up enough to once again to meet the changing needs of consumers and thrive again in a world where more and more physical stores are shutting down.