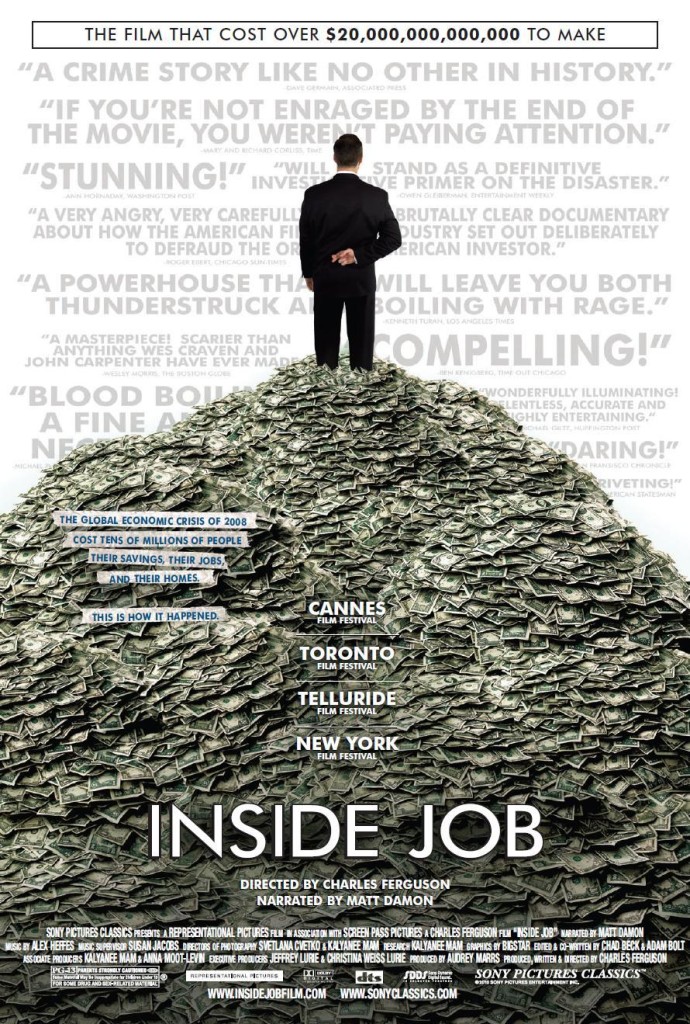

Inside Job is such an inspiring film with so many issues worth thinking hard and doing further research on. Here I just want to share with you some of my takeaways from the film, mainly focusing on the issue of conflict of interest.

Inside Job is such an inspiring film with so many issues worth thinking hard and doing further research on. Here I just want to share with you some of my takeaways from the film, mainly focusing on the issue of conflict of interest.

First let’s look at some disturbing facts. First, during the late 1990s, many IB promoted risky stocks of Internet companies that appeared to be very uncertain in terms of financial strength, which resulted in law suits and $1.4 billion settlement. Another fact is that famous credit rating agencies such as Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch provided high-risk CDOs with triple-A credit ratings which attracted numerous investors that ended up losing their shirts. Fact number three: very few academic economists foresaw the financial crisis, and even afterward, some continued to argue against reforms. Fact number four: The SEC claimed that Goldman Sachs had misstated and ignored very important facts when selling CDOs to various investors; the case was settled for $550 million but Goldman Sachs did not admit to any wrongdoing.

The way I see it is that all those facts are caused by the issue—conflict of interest, which, by definition, means that a person has a private or personal interest which is sufficient to influence the objective exercise of his or her official duties as a professional. The film mentioned four types of people that have such issue – analysts of investment banks, credit rating agencies, academic professionals, and of course, executives in Wall Street.

Analysts in investment banks are greatly motivated to report virtual-high ratings for stocks to attract clients because their firms paid them based on the level of business that they brought to the firms but not on how accurately they rate. This wicked compensation system drives the analysts to focus on creating profitable deals instead of creating safe deals. Moreover, they would rather sacrifice safety in order to bring profitable deals. This phenomenon is hard to change as long as the organizational structure doesn’t change.

The rating agencies are expected to provide unbiased professional opinions about investment. Their words are very important references for investors, so being trustworthy should be their top ethical standard. However, according to some journal articles I read, the rating agencies emphasize heavily on immunity to accountability in their operational ideas. As the excerpts from congressional hearing in the film shows, agencies defend their ratings as simply opinions that should not be relied on. In that case, it is obvious that rating agencies may also prioritize profitability over accuracy. It would appear that they are only interested in trading opinions for money.

Academic conflict of interest comes in a similar way. Many leading economists were paid consulting fees by financial service firms to shape public debate and policy. It is unnecessary for them to be accurate, because “accuracy is not something to expect in this fluctuating market anyway”, so why not just take the money from financial service firms and say what they want to hear? An example from the film would be the report written by Mishkin titled Financial Stability in Iceland, which described the exact opposite side of the truth.

Last but not least, conflict of interest of the executives in Wall Street is a big one. They somehow manipulate the market to their interest so that they could continuously feed their fat wallets, and they could walk away with huge size of bonus when things didn’t go well. Here I will just simply mention their conflict of interest in terms of fiduciary duty. To fulfill such duty, one must put client’s interests first, act in good faith, disclose everything of all materials, remain neutral, and confess if there is a conflict of interest. However, this is only an ethical code but not a requirement, and what’s worse is that, it’s an ethical code that kills income.

Last but not least, conflict of interest of the executives in Wall Street is a big one. They somehow manipulate the market to their interest so that they could continuously feed their fat wallets, and they could walk away with huge size of bonus when things didn’t go well. Here I will just simply mention their conflict of interest in terms of fiduciary duty. To fulfill such duty, one must put client’s interests first, act in good faith, disclose everything of all materials, remain neutral, and confess if there is a conflict of interest. However, this is only an ethical code but not a requirement, and what’s worse is that, it’s an ethical code that kills income.

In short, humans are greedy. This is an unfortunate but very well-accepted fact. The conservation of resources on the earth decides that when some people get richer, others get worse. With that in mind, my conclusion would be that as long as the conflict of interest exists, which is always true, and as long as it is not regulated by force, which means law that violating will cause huge penalty, investors should always keep in mind that the financial market is full of lies and dark transactions.