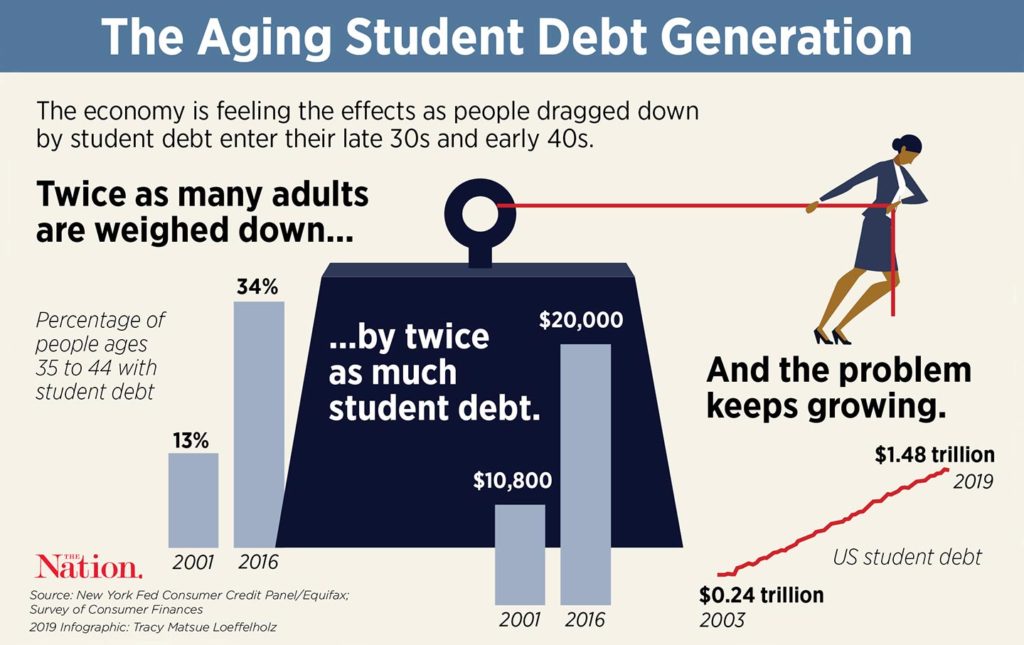

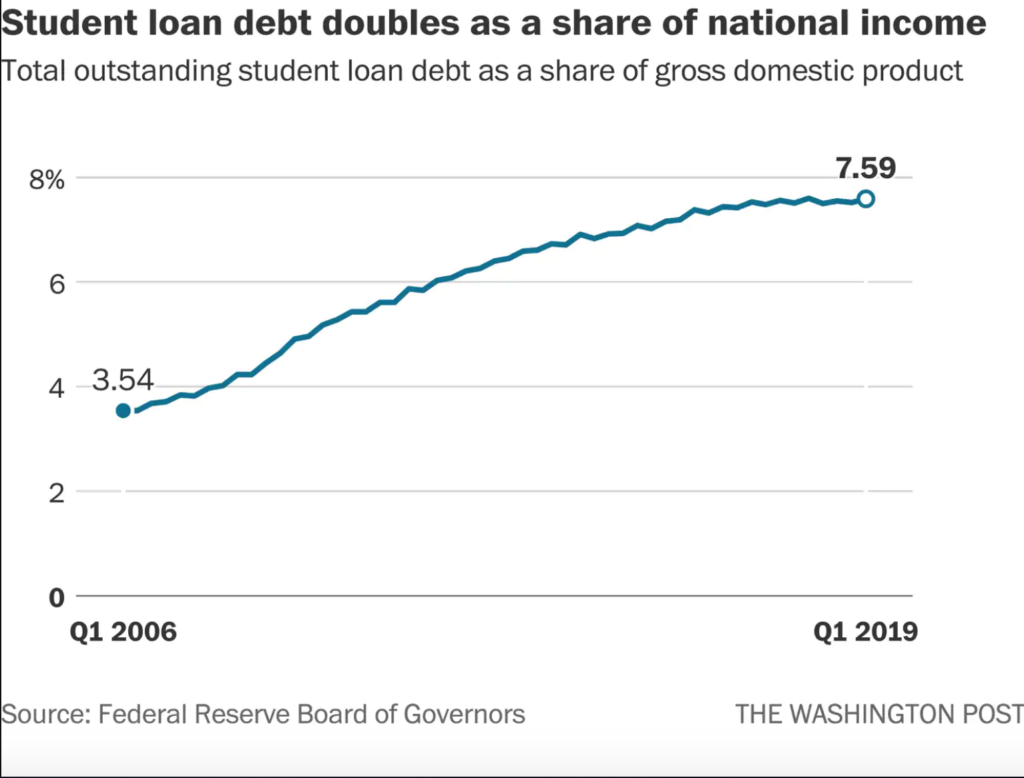

For those who earn more household income than qualified for Pell Grants but also make below the necessary means to bear the brunt of a costly higher education price tag, student loans are an attractive opportunity to finance an education. Christopher Ingraham for the Washington Post reported that American families carry more than $1.6 trillion in student debt or nearly 8 percent of national income. The number is striking, and it’s not going away any time soon. Since the 2000s, this figure has doubled, the Washington Post said.

With the pressure to earn a degree and an attractive promise of future opportunities, many bite the bullet and take out student loans. According to The Balance, the average U.S. graduate was straddled with over $39,400 in student debt in 2017. Some public service jobs and companies offer loan forgiveness opportunities for their employees, promising to pay off their worker’s college loans. Additionally, presidential candidates such as Bernie Sanders have expressed their plans to cancel student debt or make the cost of higher education free, making an attractive promise to those who understand the crippling weight of debt.

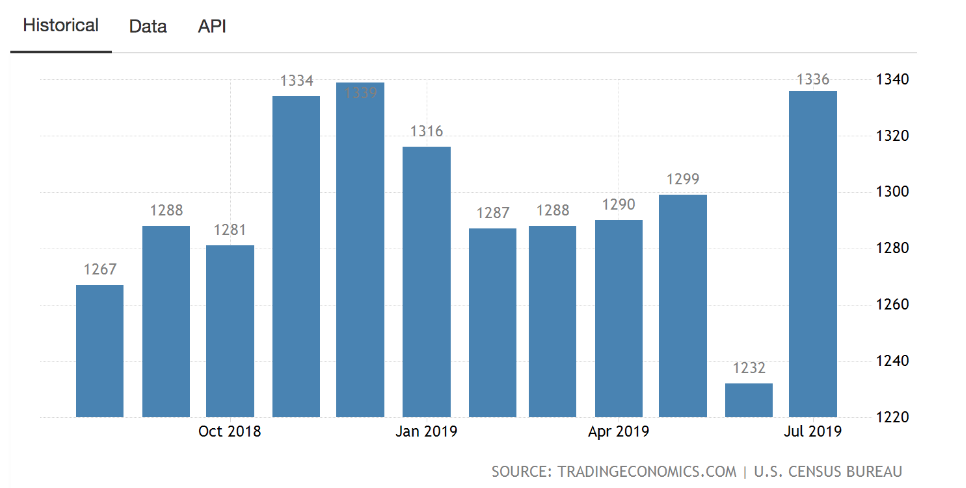

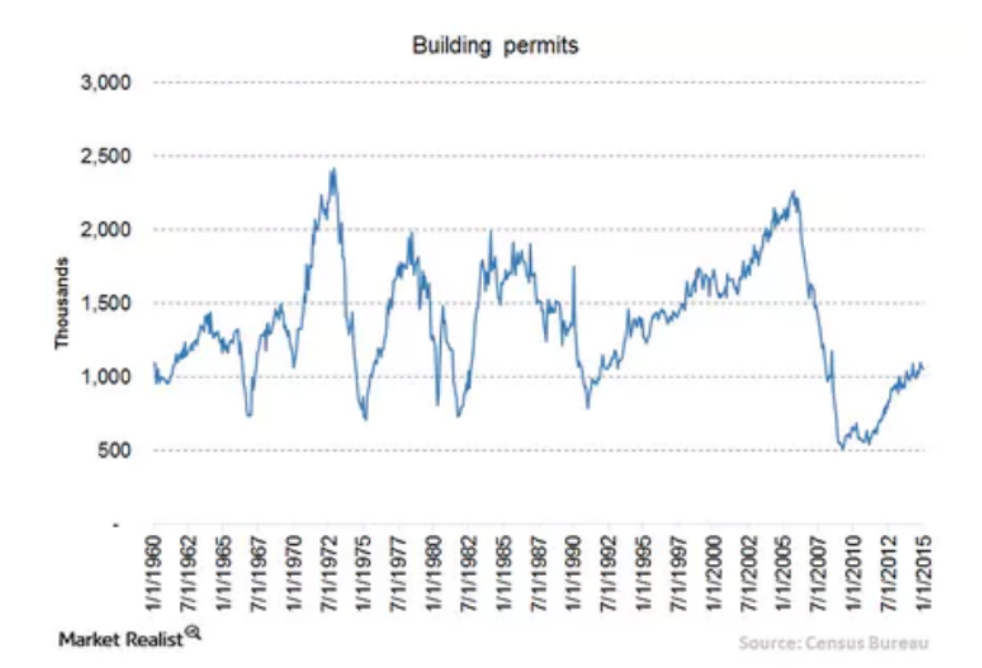

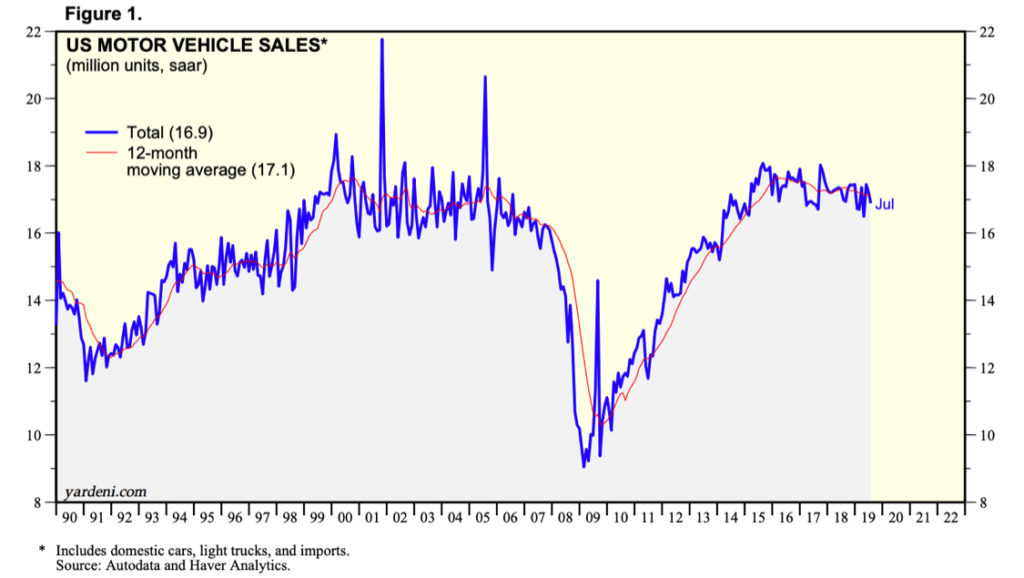

What are the implications of this financial burden? People are delaying marriage, investing less in small businesses, choosing not to buy homes and putting their income straight to paying off debt instead of saving for retirement, Ingraham said. And because of this, people aren’t spending as much money on goods and services. The Balance reported that individuals are less likely to seek out types of credit (like using credit cards or taking out car loans) because they are reluctant to borrow more money. As a result, lenders and banks receive less interest fees and slow spending affects businesses.

The real question, then, is if a college education is worth saddling piles of post-grad debt. CNBC referenced Twitter trends in which users encouraged other students to drop out of college because they claimed the student debt wasn’t worth it.

Unfortunately, there is no clear answer because traditionally, a college degree is synonymous with upward mobility and higher earning potential. It’s almost universally acknowledged, in America at least, that to be competitive in the job market, having a bachelor’s degree is the baseline expectancy.

Thirty-six percent of college graduates say their degree wasn’t worth it, according to CNBC, but experts say it’s still valuable. If basic economics centers around supply and demand, the demand for a college degree is higher than ever before, driving up the price of attaining one. Still, the solutions are bleak. The CNBC article says to avoid too much student debt, choose a more affordable college (advice that offers little solutions, in my humble opinion), and an author quoted in the piece says, “Don’t buy the typical advice that everyone seems to be throwing around these days saying college loans are the worst thing on earth. They’re not.” Still, delaying a family and withholding home-ownership sounds pretty rough to me. In the end, like most things, opportunities are a pay-to-play game and college is no exception with broader economic implications.