As with essentially every industry, the ways in which we consume sports are consistently refined by technological innovation. Radio, as well as broadcast, satellite and high-definition TV have raised the profiles of baseball, football (both kinds) and basketball. The Internet, too, modified the ways we watch sports, with the ability to analyze information no longer through merely a television screen or that morning’s newspaper. With the web fully entrenched in basic society, new streaming services offer consumers real-time information essentially whenever and wherever they want it, decreasing the need to be in front of the television for a particular program — except for sports, live content’s last bastion. These changing dynamics in streaming, doubtlessly, will further upend the model of sports consumption and threaten the viability of broadcast networks in favor of newer technology companies.

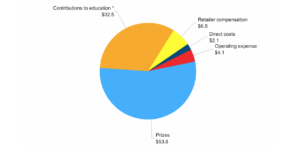

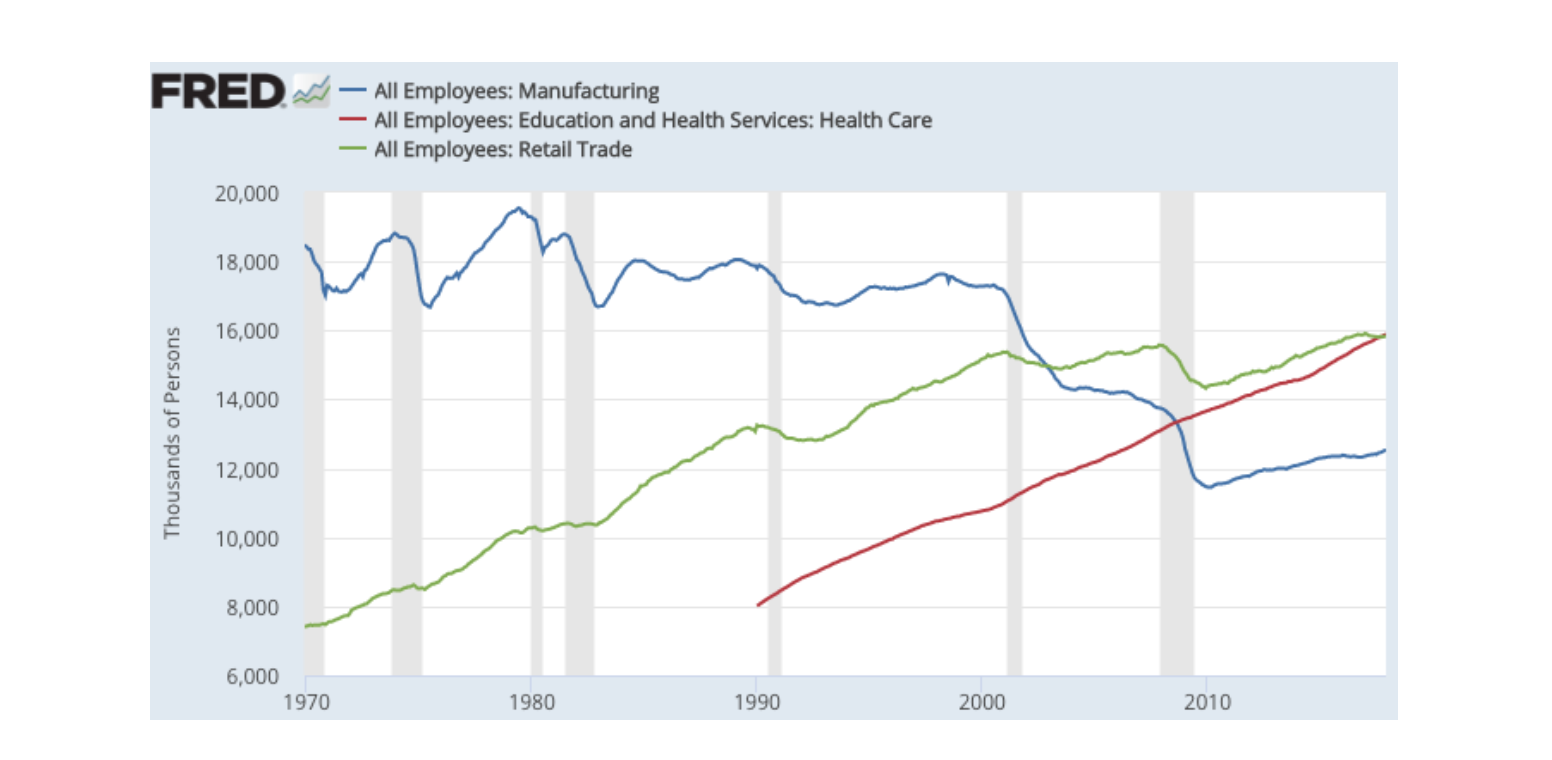

The standard over the past few decades has been for sports leagues to sign “media rights deals” with content providers, who pay to broadcast their games and content throughout the nation and the world, primarily on television [source]. Technological advancements and the practice of economic globalization have enlarged the population of sports consumers; the “rapid rise in sports costs is consistent with supply/demand theory,” creating a “constant imbalance in favor of the … nearly permanent supply shortage of top talent [while] … there are more potential bidders for their services” and content featuring the minuscule number of superstars [source]. So, the value of the sports leagues’ content has leapt and will continue to leap, because the “number of competitors is relatively large … generating continuous high demand” [source]. To date, the majority of these sports media rights deals have been with television companies, which broadcast the sporting events and highlights into homes. As Mark Leibovich, author of the book “Big Game: The NFL in Dangerous Times,” notes: “60 percent of [NFL] revenues [come] from TV over most of their history, and the ratings are going down” [source]. The leagues are paid handsomely for their content, now at the level of billions of dollars per year. To illustrate, the NBA signed its most recent national TV deal in 2014, a $24 billion, nine-year contract with Disney (through its media networks ESPN/ABC) and Turner Sports, which took effect in 2016 at a rate of $2.667 billion per year [source]. To make revenues and account for the rising costs of producing live events such as sporting events, the operators charge a fee to consumers for the channels that show it.

The research firm SNL Kagan has estimated that in 2017, “$18.37 out of the typical cable subscribers’ [$103] monthly bill was allocated just to sports networks like ESPN and Fox Sports” [source]. Sports – live content – is king. Where pay-TV providers charge more for regional sports networks, it is even higher, as much as “$20 to $25” per month. This is a raise of over five hundred percent since the start of the millenium [source].

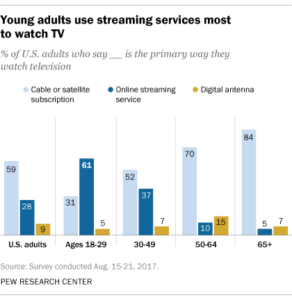

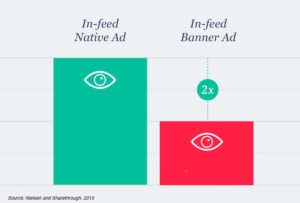

However, simultaneous with rising fees over that time period to help pay for the increasing sports rights came the new streaming services and technological advancements that have allowed people to access content, such as movies on Netflix or sports, in a mobile manner. Young people especially are not watching cable anymore; according to Pew, 61% of adults ages 18-29 use streaming services as their primary way to watch content traditionally only available on a television [source]. Choice is king for the people who are going to be consuming content for the next generation. These “a la carte” services, claims NBA Commissioner Adam Silver, are the future of how the majority of people will watch sports [source]. This season the league has started selling not just slices of the 82-game season on a game-by-game basis but also parts of games as well, in order to provide more “customized experiences to meet the needs of NBA fans” [source]. A la carte offerings are perfectly suited for the mobile-first methods of the digital natives, who will come to dominate the consumer base of the media industry.

As a result, they are the main “target in the push to increase TV-anywhere options. Unlike older viewers, they were brought up in the internet age. For them, spending a significant monthly fee on cable TV isn’t a necessity,” especially when they are paying for dozens of channels they never watch [source]. Paying as much as $25 monthly just for sports deters many from shelling out their hard-earned money, because they could pay that much to watch just the shows they want [source]. Why pay $100 for a buffet if out of three dozen items, you are only going to eat two, which cost a fraction of the buffet?

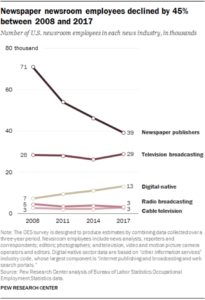

As an executive at a top streaming service company said, the industry is changing rapidly [personal conversation]. Streaming and a la carte choice options are revolutionizing how we watch content and as a result the traditional cable and network companies need to adapt.

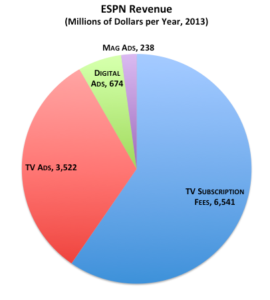

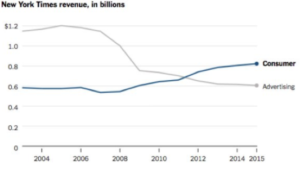

Because the “typical cable TV regional sports network (RSN) recoups less than 30% of its total revenue from advertising” they are desperate to retain as many subscribers as possible, who account for “the vast majority of revenue” [source]. National TV providers take in a similar level of revenue from subscriber fees, according to the FCC as well as an ESPN executive [personal conversation].

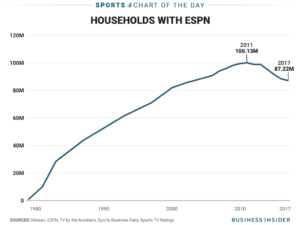

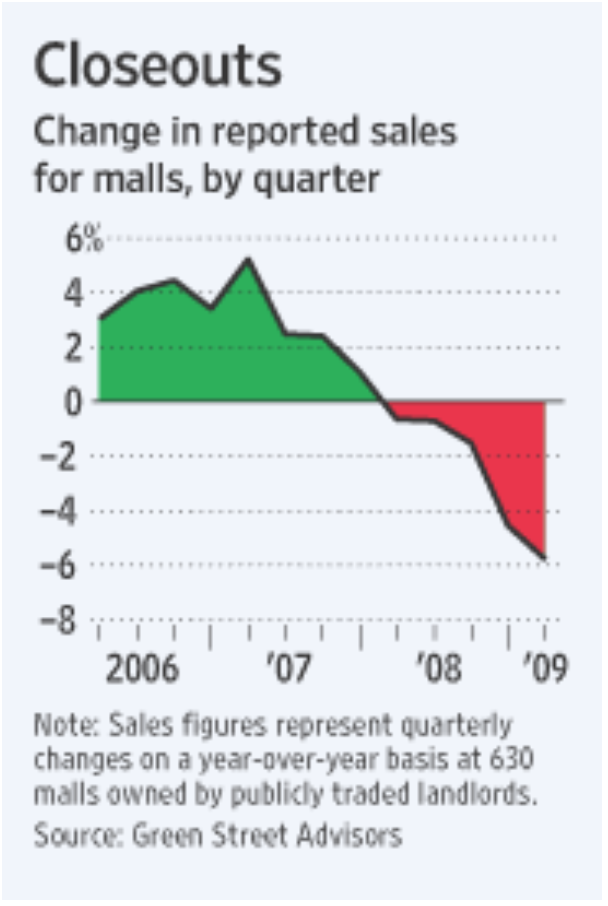

As sports rights rise, the companies charge more in fees to help break even; at $7.21 per subscriber, ESPN is now the most expensive single cable network available in one’s cable/satellite bill [source]. While the total subscribers is indeed falling, demand is not: because it is the one place live content still rules, where advertisers can be sure that people will tune in during the event, ESPN can afford to charge that much (to people who want to pay for it). For the people who want to buy the cable buffet because that is the only way they can watch their local teams or get blacked out, it is presently worth it [source]. As Rich Greenfield of BTIG wrote, “Sports is … the only content that is holding its audience viewership-wise and in turn supporting the $70 billion TV ad industry” [source]. However, the number of homes paying for ESPN declined over ten percent in the last five years, from 100 million in 2012 to just 87 million last year.

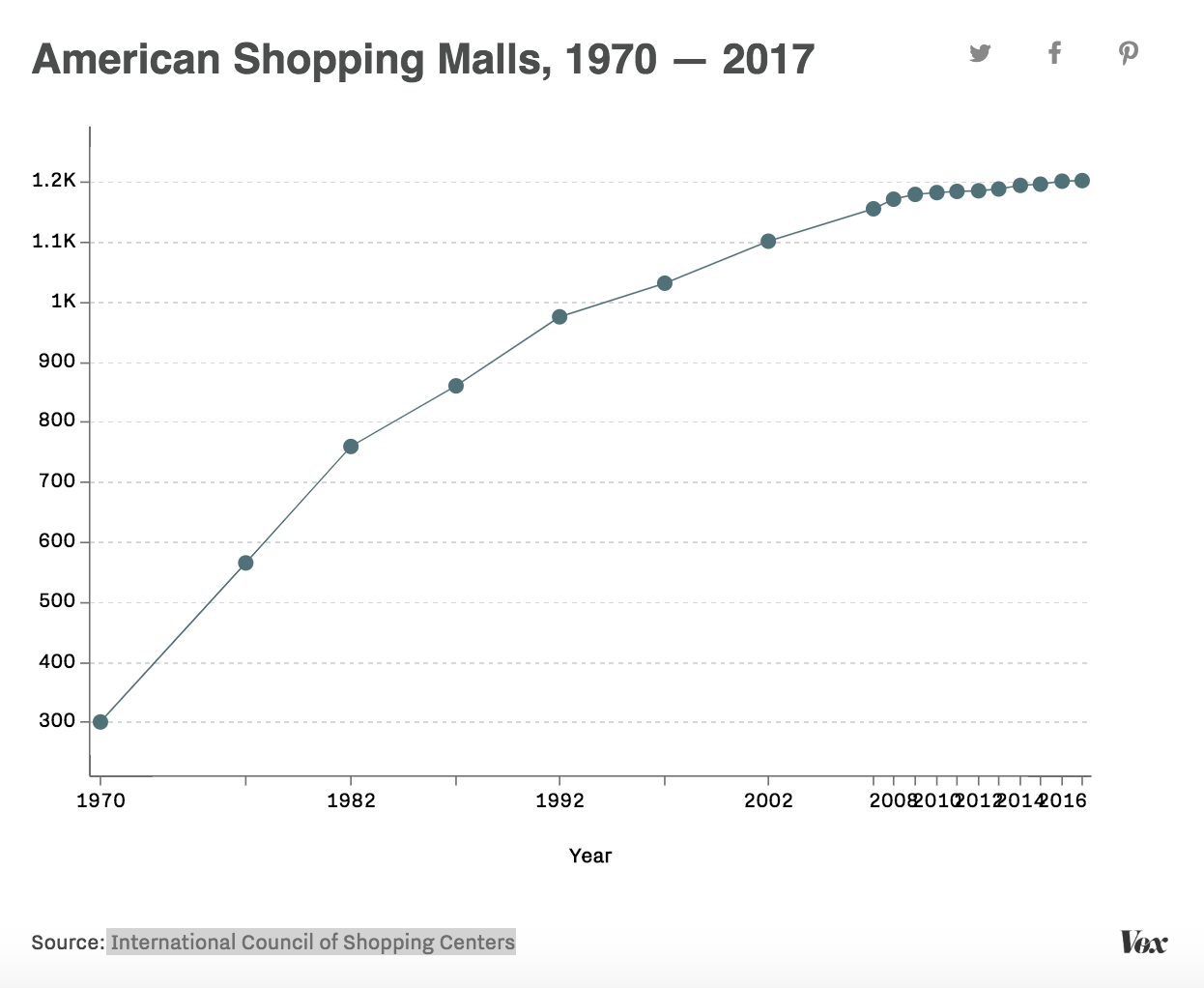

As 23 percent of U.S. households have either cancelled cable or never signed up in the first place, according to a 2016 PwC survey, the trend ESPN is facing should only continue [source]. Now more than ever, cable networks must extend or renew their TV rights to attractive sports programming. As PwC’s sports industry outlook notes, sports are essentially “the only thing keeping the lights on at the networks” [source], especially at ESPN, whose business model is solely based on 24-hours-per-day sports content. They literally cannot function without the content that has made them a behemoth in the industry.

So, cable networks are jumping headfirst into the over-the-top and streaming game, threatened by new media’s rise and the decline of their own subscriber base. To survive and continue to have success in this changing media landscape, they cannot be satisfied with their current subscribers. Like Ariel in The Little Mermaid, the networks need to be “part of that world … where the people are” [source] — which in this case is streaming and “pay-anywhere TV.” Disney is spending millions of dollars on “ESPN+”, CBS on “CBS All-Access”, Turner on “B/R Live” – their attempts at creating streaming services. It remains to be seen whether the promulgation of streaming services (along with another Disney service to be launched next year, HBO, Amazon, Hulu, Netflix…) will cause a glut of menu items for consumers, which may be where we are heading in the near future as companies look to hoard their own intellectual property and control sports rights [source]. However, in sports, the possibility of a large media or technology conglomerate claiming access to a near-entirety of a league’s offerings could lower consumer angst. NBA Commissioner Emeritus David Stern wonders about the “unique possibility to have one buyer on a global basis. It could be Apple, Amazon, Hulu, Facebook, Google, AT&T—could be almost anything” [source]. The current battle over regional sports networks will perhaps be a test case.

In 2002, the New York Yankees developed the Yankee Entertainment and Sports (YES) regional sports network to strengthen the value of its content for local consumers and develop new revenue streams. Major networks such as ABC or FOX had only broadcast select numbers of games per season to people around the country; regional networks proffered the opportunity for viewers to watch nearly all their home team’s games. The Bronx Bombers’ enterprise introduced the RSN epoch: many teams in MLB and the NBA now have launched their own networks to take advantage of local revenues; in the MLB, these contracts are worth anywhere from $1.5 billion (Arizona Diamondbacks) to $3 billion (Los Angeles Angels) over twenty years [source]. Markets like Los Angeles or New York have greater demand and numbers of viewers for the same content as Arizona, therefore those media rights deals rake in as much as double the revenues (and is a key reason why the Angels changed their city name from “Anaheim” to “Los Angeles”) [source]. These dramatically different local media rights deals also affect competitive balance and league health: The Los Angeles Lakers’ local media deal dwarfs any other NBA franchise’s by about $25 million; they were the most profitable team in the league despite missing the playoffs for five consecutive years [source]. Moreover, in MLB, owning significant portions of these extra revenue streams has helped teams like the Red Sox and Yankees dominate free agency and acquire the “star talent”, like Alex Rodriguez, who drive content values high [source].

Over the last two decades, Fox acquired in exchange for a “yearly licensing check” majority stakes in 22 RSNs, the value of which has now ballooned to $44 billion due to all the exclusive premium sports content, according to Guggenheim Securities [source] [source]. And so it goes that Disney’s recent acquisition of 21st Century Fox will reshape not just the movie industry (decreasing the number of major studios from six to five) but also sports content [source]. Fox’s regional channels serve around 61 million subscribers around the country, a godsend to cable operators and a would-be boon to technology companies looking to seize market share and eyeballs from one another. The 22 RSNs that Fox owned will have to be divested as a result of the deal, to prevent “cable television subscription prices from rising even higher … and ensure that sports programming competition is preserved in the local markets,” according to Makan Delrahim, assistant attorney general and head of the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division. “American consumers have benefitted from head-to-head competition between Disney and Fox’s cable sports programming” [source].

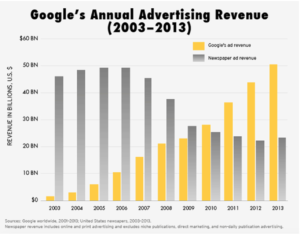

The competition will only get fiercer, as more players enter to gain direct consumer attention, arguably the most valuable market good there is. The forthcoming battle for sports media rights will truly be the “ultimate test of the supply/demand equation, an underlying principle of the free enterprise system and free market economy” [source]. Fox’s 22 MLB regional sports networks is now up for grabs, and who is bidding for them will be a harbinger of the coming battle for sports content come the next decade once deals expire for the major leagues — and for viewers in the future of the 21st century. Consistent with supply and demand economics, the values of sports rights will rise, with the same amount of content, the escalating emphasis of live programming for advertisements, and more possible buyers. This could drive vicissitudes of fortune for traditional broadcasters. A Defcon 1 scenario would be if a traditional broadcaster loses out entirely on a sports rights deal. Amazon, Twitter, Alphabet’s YouTube, and Facebook have each already made forays into paying for live sports, streaming NFL Thursday Night Football, NBA games, and MLB games, respectively, via their over-the-top services. The Financial Times notes that these moves are “part of a wider shift toward so-called “skinny bundles”, whereby consumers are offered a smaller range of channels for a fraction of the price of a full cable package” [source]. Amazon has already put in a bid for the RSNs, if not merely to drive up the cost for another winner, then to implement them into Amazon Prime services similar to their actions with Thursday Night Football on the chance they end up claiming the networks. “It [would increase] digital advertising opportunities for Amazon, which is growing its market share against Facebook and Google. Perhaps most importantly, it brings even more people into the Amazon tent, exposing them to all of the products and services Amazon offers,” according to CNBC [source]. On another front, no less than Fox chief Rupert Murdoch has said that “Facebook is coming for sports;” Dan Reed, a Facebook executive, says that “sports is a natural fit” [source]. Having dipped toes into the water, the large technology companies are going to dive wholeheartedly into the sports media business in the near future. Even if tech companies do not win this RSN test run, they will no doubt be major players in the bidding for the future sports rights, 16 major auctions of which are coming worldwide over the next half-decade, according to GroupM [source]. Claiming some if not all of those rights and shoring up their relatively nascent streaming services will reshape media offerings.

The tech giants’ enormous capital reserves [source] that could drive up the bidding to an exorbitant level ($4 billion for the NFL? $2 billion per NBA season?) probably won’t destroy the financials of some traditional broadcasters by the early 2020s, but that combined with growing rate of subscriber drop-off (could only 50 million homes be cable subscribers in five years?) will hamper networks’ abilities to spend as much on rights the next time around. It is quite a possibility that there could be an internecine battle between broadcasters, resulting in a pyrrhic victory for the winner. Already, rights have gotten so expensive that ESPN could not win the bidding for the Champions League and accentuate its investment in MLB rights [source]. Come the second wave of these types of deals in the late 2020s, the costs could deter some broadcasters from seriously bidding for them. Perversely, over the long term, rights deal valuations may fall as broadcasters drop out, although other technology companies could enter the fray and stabilize or even drive up pricing. As David Stern literally said today, “you have to look to the future or you die” [source]. Because broadcasters are slowly coming around to reality out of dire necessity, they may survive in the short term. In another decade, in 2030, though, we may all be watching sports through the services of our Amazon or Alphabet overlords, ironically with more customizable options.

Sources:

https://business.comcast.com/about-us/our-history

https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/yes-network#section-overview

https://digiday.com/media/what-is-over-the-top-ott/

https://money.cnn.com/2017/07/19/investing/apple-google-microsoft-cash/index.html

https://www.digitaltrends.com/movies/too-many-streaming-services-netflix-amazon-disney-att/

https://adage.com/article/media/pwc-report-sports-m/311578/

https://mashable.com/2015/07/23/nba-league-pass-new-deal/#pRXrKXEIJgqz

https://variety.com/2018/digital/features/olympics-rights-streaming-nbc-winter-games-1202680323/

https://www.businessinsider.com/sports-media-rights-revenue-poised-to-grow-2017-12

https://www.21cf.com/news/21st-century-fox/2014/21st-century-fox-acquire-majority-stake-yes-network/

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/05/espn-layoffs-future/524922/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SXKlJuO07eM

https://variety.com/2018/biz/news/disney-21st-century-fox-justice-department-approval-1202859241/

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/youtube-amazon-fighting-sports-streaming-supremacy-114738861.html

https://www.latimes.com/business/hollywood/la-fi-ct-disney-fox-sports-nets-espn-20171206-story.html

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/09/the-many-problems-with-moneyball/245769/

http://time.com/money/4590614/cable-bill-sports-cord-cutting-streaming/

http://www.snl.com/Sectors/Media/

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B078LTFG52/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1

https://www.businessinsider.com/espn-losing-subscribers-not-ratings-viewers-2017-9

http://time.com/money/4590614/cable-bill-sports-cord-cutting-streaming/

https://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/columnists/ct-sports-tv-future-spt-0828-20160826-column.html

http://www.nba.com/2014/news/10/06/nba-media-deal-disney-turner-sports/

https://beonair.com/history-of-sports-broadcasting/

https://transition.fcc.gov/enbanc/121897/anshand.pdf

https://www.ft.com/content/2234f4da-3ef8-11e7-82b6-896b95f30f58

https://www.latimes.com/business/hollywood/la-fi-ct-disney-fox-sports-nets-espn-20171206-story.html

http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/12/21/4-one-in-seven-americans-are-television-cord-cutters/

http://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=1735937

Personal interview/lecture, ESPN executive, Spring 2017

Personal interview/lecture, Professor Jeff Fellenzer, USC, February 2017

Personal interview, Professor Jeff Fellenzer, USC, November 2018

Personal interview/conversation, Perform Group executive, summer 2018