By Roy Pankey

I don’t like to throw away my money. But in late October of this year, after the California Mega Millions jackpot topped $1 billion, I bought a handful of lottery tickets. I even waited in line with dozens of other hopefuls for half an hour at Bluebird Liquor in Hawthorn, where the lottery tickets are rumored to be extra lucky. Needless to say, I didn’t win.

Neither did California schools.

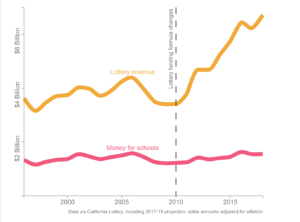

The state lottery is practically printing its own money. Though California Lottery hasn’t made public its total revenue for the 2017-18 fiscal year, the California Department of Education (CDE) projected total sales of $6.75 billion for this period, an historic high. That’s more than total revenue of Fortune 500 companies like Ralph Lauren, Ulta Beauty, Harley-Davidson, and Hasbro.

This sum comes after several years of increasing sales for the California Lottery, which sounds like a win for the state’s schools. Yet even as the lottery is selling more tickets than ever before, California schools aren’t receiving any additional funding. In fact, lottery payouts to education are essentially the same from a decade ago.

How can this be? Eight years ago, state legislators changed the requirements of the lottery system.

When 57.9% of voters passed the California State Lottery Act in 1984, they mandated that 34 percent of total lottery revenue be paid to public education. This law withheld until lawmakers abolished that requirement in 2010. The new law requires that the lottery “maximize revenues for public education by operating as efficiently as possible.”

Ticket sales dragged during the Great Recession, and legislators loosened reigns on the lottery to increase jackpots and sales overall. They knew the percentage of each dollar paid to education would fall but hoped the increase in revenue would lead to an increase in total payout to schools.

It’s not happening.

In its public education contribution report for the 2017-18 fiscal year, the California State Lottery indicated that it raised just under $1.7 billion for schools.

At first glance, that sounds like a huge, great number. (First graders shall never want for colored pencils again!) However, education payout represents just 25 percent of the $6.75 billion in projected sales for the year. In past years, the payout percentages were much higher. The lottery is making more money than ever, but schools aren’t seeing any of it.

Zahava Stadler of EdBuild, a non-profit that closely studies education funding, told The Press Democrat, “The fact that education dollars have remained pretty flat tells you that more and more what the state is doing here is running a casino, rather than funding public schools.”

Funds raised by lottery ticket sales account for less than 1.5 percent of all education funding in California. Money is distributed among K-12 schools, California State University, University of California, community colleges, and various other educational institutions. About 80 percent of payouts go to K-12 education.

In a statement on its website, the CDE says the money it receives from state lottery ticket sales “represents only a small part of the overall budget of California’s K-12 public education that alone cannot provide for major improvements in K-12 education.”

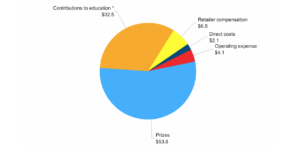

Since its inception in 1985, the California State Lottery has contributed more than $32.5 billion to education. Its all-time biggest expense—a whopping $53.8 billion—has been awarded to lucky prize winners.

Distribution of Revenues (in billions) October 3, 1985 – June 30, 2017 (Source: California State Lottery)

Distribution of Revenues (in billions) October 3, 1985 – June 30, 2017 (Source: California State Lottery)

In October 2017, officials who run the Mega Millions game were concerned that frequent, smaller jackpots—say, $100 million or less—would result in fewer ticket sales. They thought people would become too familiar with prizes like these and would be discouraged from buying any tickets at all. Gordon Medenica, head director of the Mega Millions Group referred to this phenomenon as “jackpot fatigue” in an interview with The Washington Post.

Now, the Mega Millions pools are paid out much more infrequently, allowing them to swell and swell to unprecedented amounts. Adding to the paucity of payouts was an increase of numbers to choose from on each ticket, as more numbers decreases a player’s odds. Another change that powered tickets sales was the increase in the price of the tickets themselves. They now cost $2, double the prior price.

The California Lottery estimates that more than 19 million people played last year. That’s more than half the state’s population old enough to gamble. In California—like in most states with a lottery system—vendors sell a majority of tickets to low-income individuals.

An analysis by LAist of two years of lottery ticket sales in California found that:

- Most tickets are purchased by the poorest fourth of census tracts in virtually every county.

- Most tickets are purchased in Southern California census tracts with high Latino and Asian-American populations.

- Most tickets are purchased in Southern California’s Los Angeles, Riverside, San Bernardino, Orange, and Ventura Counties.

Dr. Timothy Fong, director of the gambling studies program at UCLA, told the publication, “The lottery does seem to be more harmful for, as you can imagine, lower economic communities, ethnic minorities.” Communities spending the most on lottery tickets are the same communities who are in most need of the system’s education funding.

That disparity hasn’t happened by chance. With the help of high-powered advertising agencies, the lottery markets to California’s diverse populations.

To reach Asian-Americans, the lottery has developed products like its Lunar New Year ticket, whose jackpot is $888. The number eight is associated with wealth in Chinese culture.

In October, marketing agency David&Goliath placed the winning bid for California Lottery’s $295 million account as part of a five-year contract. Together, the two will continue marketing to California’s diverse communities and working toward the Lottery’s goal of becoming “the largest lottery in the U.S.” (It trails only New York.)

Of all California cities with populations over 50,000, Westminster, located in northern Orange County, sells the most lottery tickets per capita. The city sold $668 worth of tickets to each resident in 2016 and 2017. The median household income in Westminster is $55,287, while the median household income for the state is considerably higher at $67,739.

Some other California cities selling the most lottery tickets include Huntington Park, Inglewood, Hawthorne, and Compton at $392, $359, $330, and $323 per capita, respectively. All of the median household incomes in these cities are even lower than that of Westminster.

The Mega Millions used to work like this: Players chose five numbers from 1 to 75 and a Mega number from 1 to 15. Odds of winning the jackpot were 1 in 258,890,850.

Since officials altered the Mega Millions tickets, players now choose five numbers from 1 to 70. They still choose a Mega number, but the range increased to 1 to 25. Now, odds of winning the grand prize are 1 in 302,575,350, meaning my chances of getting rich decreased by more than 16 percent.

Odds that schools will win big? Still unclear.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.