The past year has been a trashy year, and not just because of the United States’ tumultuous political climate. Rather, the problems with trash have become more central to environmental and economic reform than ever before.

For some, plastic straws sparked the conversation when Seattle banned single-use plastics this past summer, an event that swept the internet and inspired mass numbers to act against pollution. The real trash tale, however, is much grimmer than the sliver of environmental hope provided by any limit placed on plastic drinking tubes. With the United States producing the most waste globally and China recently enacting limitations on how much foreign garbage it will import, the trash is piling up. Americans are now coming face-to-face with a hard reality: reduce waste or suffocate under the consequences.

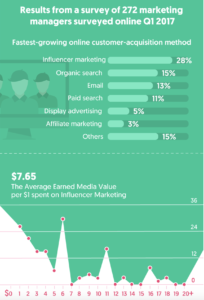

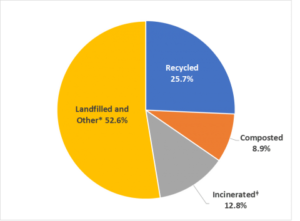

It’s no secret that the United States has a huge problem with waste. Though home to only 4 percent of the world’s population, the U.S. produces more than 30 percent of the planet’s total waste, according to a report by Frontier Group. The average American throws out 7 pounds of materials each day, with over half of all materials scrapped by homes and business ending up in landfills and only a third being recycled or composted.

Source: Frontier Group

The expanding $60 billion solid waste industry in the U.S. indicates the large-scale effort required to domestically manage all of the garbage produced. At this rate, however, the U.S. has not been capable of managing all of its own trash. While the wasteful reality of the U.S. may be “Land of the free, home of the brave… and lots of garbage in between,” the U.S. has made every attempt to steer away from such a reputation within its physical landscape. As a result, the U.S. has been exporting about one-third of its recyclables, with half going to China, according to NPR. To paint a global picture, nearly half of the planet’s plastic trash since 1988 — including single-use plastics, food wrappers and plastic bags — has been sent to China to be recycled into other forms of plastic goods, according to The Verge.

At first, this was a mutually beneficial trade agreement for both the U.S. and China: the U.S. would have significantly less trash to deal with on its home turf, and industrial China was able to acquire foreign currency while turning plastic into profit. The USC-US China Institute reported that, as time went on, the U.S.’s biggest dollar value export to China was trash, with Bloomberg reporting that Americans shipping more than $5.6 billion worth of scrap to China in 2016. At its peak, the Chinese recycling industry supported nearly 12 million jobs, and the recycled plastic was being turned into products valued over $64 billion a year. Environmentally, recycling also provided China a means to save energy when compared to industries like mining and logging. It was a business model that seemed to be indestructible.

Source: Bloomberg

Come 2012, however, what appeared to be an untouchable, powerful and productive market took a turn for the worst. China’s labor market shrunk for the first time. U.S. scrap exports to China fell for the first time since 1996. The next year, more foreign direct investment went to Southeast Asia than China. Then, the big one hit at the end of 2017: China notified the World Trade Organization that it had decided to ban imports of 24 categories of solid waste, effective March 2018. Now that China is post-industrial and rests on more financially-steady ground, the trash ban is the country’s next step toward improving the quality of life for its citizens by reducing emissions and creating a more sustainable nation.

“There was no doubt there was a great deal of discontent within China, and if they had announced a five-year transition, they would have faced domestic opposition,” said Dr. Douglas Becker, an international relations and environmental studies professor at the University of Southern California. “The reports coming out of the areas near the largest trash dumps in south China are a lot worse that people realized, and not by a small amount. So they sensed that they needed to do something fairly drastic.”

China is not backing down from the ban. Considering this change was essentially put in place immediately, though, the policy threw the U.S.’s trash processing system for a whirlwind.

“If it doesn’t go to China for two to three months, you’ll have 1 million tons of paper stacked somewhere in the American economy,” said Ranjit Baxi, president of the Brussels-based Bureau of International Recycling, to Bloomberg.

Baxi was exactly correct, as the U.S. is already feeling the effects of the ban. The Washington Post reported that states like Massachusetts and Oregon are changing some of their waste restrictions, dumping recyclable material into landfills. In California, the effect has been “heavy” according to a Waste Dive report that has been tracking the outcomes of China’s scrap limitations since Nov. 2017. Locally, an LA County Sanitation Districts official told Marketplace that 15-20 percent more material is ending up in the Puente Hills facility as residual contamination. Managing waste domestically in a sustainable fashion already posed a significant challenge, but now with China out of the picture, trash is pouring out of American landfills.

“Depending on the areas and cities, landfills are filling a bit more quickly, and I know there has been some talk about large cities trying to find the landfill space further and further from their city centers, perhaps even in different states,” Becker said. “That tends to engender quite a bit of opposition.”

The scariest thing? Even though the trash trade went on for decades, the ban has only been in practice for less than a year, but the consequences are already eliciting drastic results.

Source: Asian Review

China’s decisions to limit its importation of trash is like a form of self-care: by cutting out toxic relationships, the country is now able to focus on improving the life quality of its citizens. America, however, cannot function without exporting its scrap, so Southeast Asian countries have become China’s replacement. Thus, China itself may be on a greener path, but the waste problem at large simply has simply shifted from one landmass to the next, raising the same environmental issues for different people groups.

“I think the same concerns the Chinese had with the areas of toxicity are also valid in South and Southeast Asia where the trash is going,” Becker said. “As far as Southeast Asia is concerned, for some, they do want the materials to help them industrialize, but it’s largely a means by which to make money. So, I imagine [importing trash] would be pretty bad for the local populations, the same reason why the Chinese chose to end this.”

In essence, Southeast Asian countries are importing waste for similar reasons that China did. Recycling was an introductory means toward progress, but processing trash is not a long-term environmental or economic solution. Countries such as Malaysia and Thailand are already expressing frustration at the burden the increasing amounts of trash have placed on the countries.

Steve Wong, managing director of Fukutomi, a plastic recycling and trading company in Hong Kong, told Asian Review that Southeast Asian nations cannot handle even half of the volume China imported in the past.

“The abrupt China ban leaves [Southeast Asian] countries unprepared to receive the huge influx of waste,” Wong said.

Waste in Thailand. Source: Asian Review

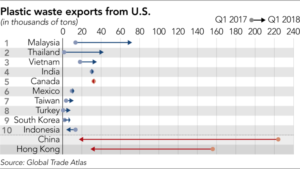

From Jan. to March 2018, Thailand imported 121,000 tons of trash, a 17.7 percent increase from the same period a year before, according to data released by the Global Trade Atlas. Malaysia’s trash importation increased fourfold, and Vietnam, Taiwan and South Korea also have seen significant increases. Meanwhile, China and Hong Kong have seen more than 90 percent decreases.

Just because China banned the import of scrap in favor of the environment, however, doesn’t mean Chinese recyclers were financially happy with the decision. According to Wong, an estimated 1,700 licensed Chinese recyclers were affected by the import ban, and about 40 percent of them have relocated their operations to Southeast Asian countries.

“Up to 1,000 Chinese businessmen are asking for licenses to do recycling in Thailand, with total investment of up to 250 million baht ($7.6 million),” said a senior official at Thailand’s Industry Ministry. As a result, Thailand has put an indefinite hold on licensing to counter Chinese land ventures, according to Asian Review.

Between fights for land, trash and the environment, the entire trash trade narrative boils down to the same core problems: How do we fix our massive trash habits, and why is waste so problematic?

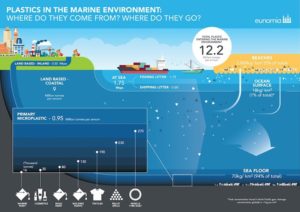

Frontier Group lists several environmental consequences of waste production. Most notably, about 42 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions are created from the production, transportation and disposal of goods, which is a direct contributor to global warming. Garbage that does not get dumped in landfills or recycling plants often ends up in the ocean, which is detrimental for marine biodiversity, habitats and overall water quality. Air quality is affected. Discarded materials waste natural resources. Landfills decrease property value and overall quality of life. The list, really, could go on forever.

U.S. citizens, however, can only do so much because the larger issue of waste is a top-down problem. Though each American disposes an average of 2,555 pounds of materials per year, those materials only make up 3 percent of all solid waste in the United States. When a majority of waste comes from industrial processes like mining, manufacturing and agriculture, encouraging individual choices, ultimately, can only make so much of a difference.

So, as a quick anecdote, let’s return to the plastic straw ban. Though Seattle issued a ban in July on all single-use plastic straws and utensils at all food service businesses, it was not the first city of its kind to enact such a ruling. Seattle made the plastic straw ban trendy, though, because the city is the birthplace of Starbucks, which is an inherently trendy brand. Therefore, the small-scale straw issue became widespread as Seattle-based Starbucks no longer could utilize their famous green single-use plastic straws.

As the negative view of plastic straws caught on, many were suddenly switching their plastic straws for paper or stainless steel ones and felt they were saving the planet as a result. The truth? There are eight million tons of plastic streaming into the ocean annually, and plastic straws only make up 0.025 percent of that waste, according to National Geographic.

“[The plastic straw ban is] not going to solve the problem, but it’s at least raising awareness for a lot of people — an increasing amount of recycling, pressure being placed on corporations in particular to try and manage some of the packaging issues,” Becker said. “There’s a greater public awareness as a result of this. I think that’s probably going to continue.”

The plastic straw ban is more of a poster child for larger environmental and economic problems associated with waste than it is the actual solution to waste itself. Even if the U.S. were to completely rid of every plastic straw in sight, the U.S.’s need to export recyclables and deal with the environmental consequences of trash would not be impacted. The plastic straw ban, however, does have the potential to start a chain reaction with eradicating bigger forms of plastic. With China’s limitations on trash and increased awareness surrounding waste, maybe in coming years the world won’t be such a trashy place after all.