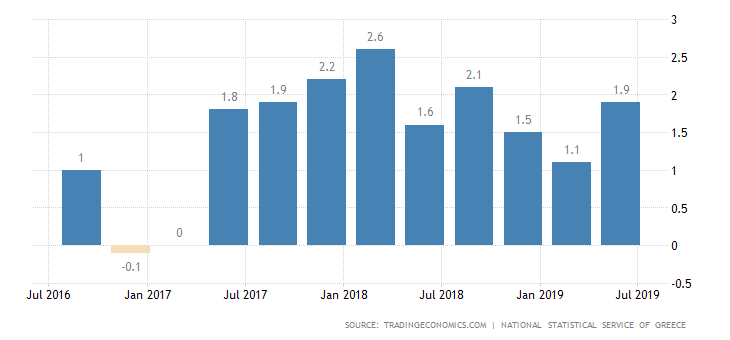

After being in a debt crisis since 2009, consumer confidence is at its highest level since 2000 and GDP is expected to have almost 2 percent growth following the fiscal year.

How did Greece’s debt crisis get even worse after 2015?

Back in 2015, Greece was still trying to move in a positive direction following an already six year debt crisis. So when the July elections of 2015 came around, the people believed they needed drastic change and elected Alexis Tsipras and his super “left-winged” Syriza party to try and move the economy forward for a change. Tsipras implemented corporate taxes, regulations on international trade, and tons of entitlement programs that the government could not pay for. All of these policies made the debt escalate further which created a major recession.

The Change in the Right Direction!

Greek citizens became extremely frustrated at the results of Tsipras and the Syriza party through their term, and earlier this year in the July elections opted to elect Kyriakos Mitsotakis, leader of the fiscally conservative “New Democracy” party. After years of different right and left-winged parties running the economy, Greece finally has returned to the two-party system that had them flourish in 2000. Many people worldwide were scared prior to the election that Greece would lean toward right-winged extremism”, but “The New Democracy” party beat out the right-winged “Golden Dawn” party to ensure that democracy is still alive and can flourish again in Greece. Mitsotakis did just that, reversing the socialist agenda that plagued the economy prior to his election. Mitsotakis has implemented corporate tax cuts, lifted restrictions on international trade, and limited entitlement programs within Greece since the government cannot afford it yet. He will continue to reform and work on these policies in the next couple of years as well. These policies are predicted to help the economy grow further and cause GDP to have 2 percent growth at the end of this fiscal year saw. Even though Mitsotakis has just been elected, many economists now believe the Greek economy is stable and will continue to get even better as the economy is at its best since 2000.

Returning to Normality!

Greece’s capital controls and restrictions are a thing of the past with Mitsotakis in office. Unemployment is still the biggest issue in the Greek economy, but it’s down to 17 percent from its peak at 28 percent in 2013. Granted, many Greek workers do not get fired, as discussed in class last week, so people of college-age or in their young 20’s have a hard job getting employed. That problem is not only an economical issue but a political one as well which makes it hard to judge Greece’s economy on that 17 percent unemployment. Because international trade does not have as many restrictions anymore, Greece is all of a sudden a player in the foreign market, which in the next couple of years will spur the economy to grow even more. Another policy Mitsotakis has implemented is the banks getting rid of “non-performing” or “bad” loans which is set to help grow the economy as well. Greece’s new finance minister Christos Staikouras plans to re-pay 3 billion of Greece’s 8.5 billion euro debt this year as well. All of these policies are not only moving the Greek economy forward but also preventing it from future crashes.

Sources: https://www.ft.com/content/c2c42066-d93c-11e9-8f9b-77216ebe1f17 https://tradingeconomics.com/greece/gdp-growth-annual https://www.southeusummit.com/europe/greece-marks-major-economic-milestone-in-advance-of-a-month-of-financial-planning/