Silicon Valley acts as the entrepreneurial hub and home to major tech companies and start-ups on the west coast. TV series and movies depict this culture of wealth and fame. But this San Fransisco tech hub is not the only city in the United States that fosters this type of creative and financially flourishing environment. Over the past 10 years, start-up culture has spread throughout the United States and is flourishing in cities like Boulder, Colorado and Austin, Texas. Boulder has a population of approximately 100,000 people and in a study done in 2010 by the Kauffman Foundation, Boulder has six times more high-tech start-up’s per capita than the nation’s average and twice as many per capita than San Jose-Sunnyvale in California.

Normalizing this start-up culture has helped Boulders economy flourish, but not all metropolitan cities have the financial backing and culture that could support this shift. Though the majority of millennials in metropolitan areas understand the benefits of integrating small businesses and technology into their city, older generations and individuals with a traditional mindset have difficulty coming to terms with this non-traditional shift in career trajectory. But what makes a city a successful hub for start-up and venture capital culture, is the willingness to explore opportunity and advancement for your environment. Start-up culture is fostered by problem-solving, so is it possible that down the line more cities will become tech hubs and how will this affect entry-level jobs and cities economic development? The cities economic and social structure needs to be supported by the infringement that incorporating entrepreneurial opportunities will bring. Automation, data analysis and other forms of technology will continue to grow and change the systems placed by standard job structures, and the infrastructure of the city around it must be prepared for the change it will bring as well.

Innovation impacts socio-economic objectives.

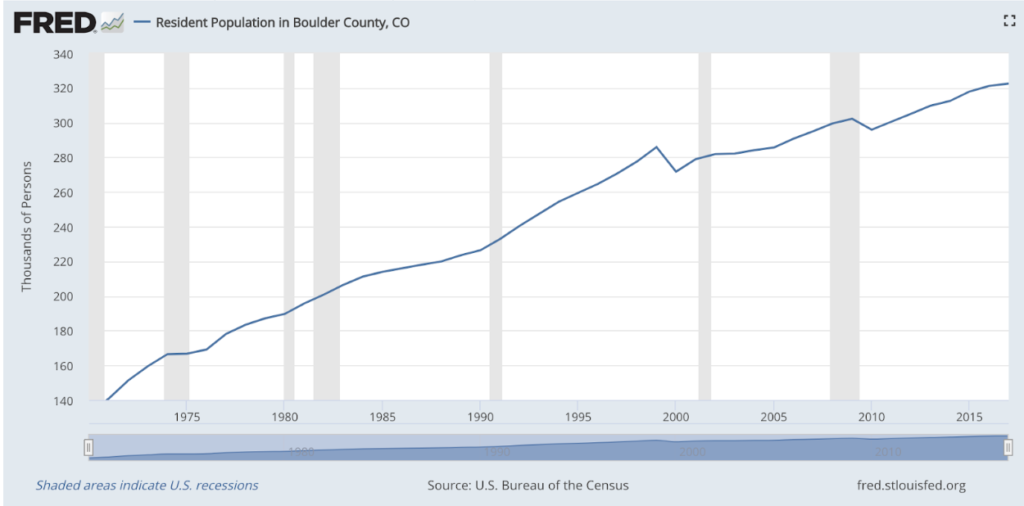

Incorporating new practices and innovative efficiencies into a new market will have a positive effect on the socio-economic objectives of a city because incentivising an entrepreneurial culture will ultimately resolve unmet needs. Unmet needs meaning desired services, tangible inventions and reforms to existing systems. Opening small businesses and branches of larger corporations and remote offices also mean that there will be more employment opportunities in a city. Whether the level of entry is higher than a cashier or waiter type position, the market will continue to grow and change with an influx of jobs being introduced either way. This incentivizes people to relocate to these cities, like Boulder or Austin, where the market is rapidly increasing with more complex executive positions, that require a form of expertise. For the past 30 years, the resident population in Boulder County has been steadily increasing, which proves that the growing economy is attracting more people every year.

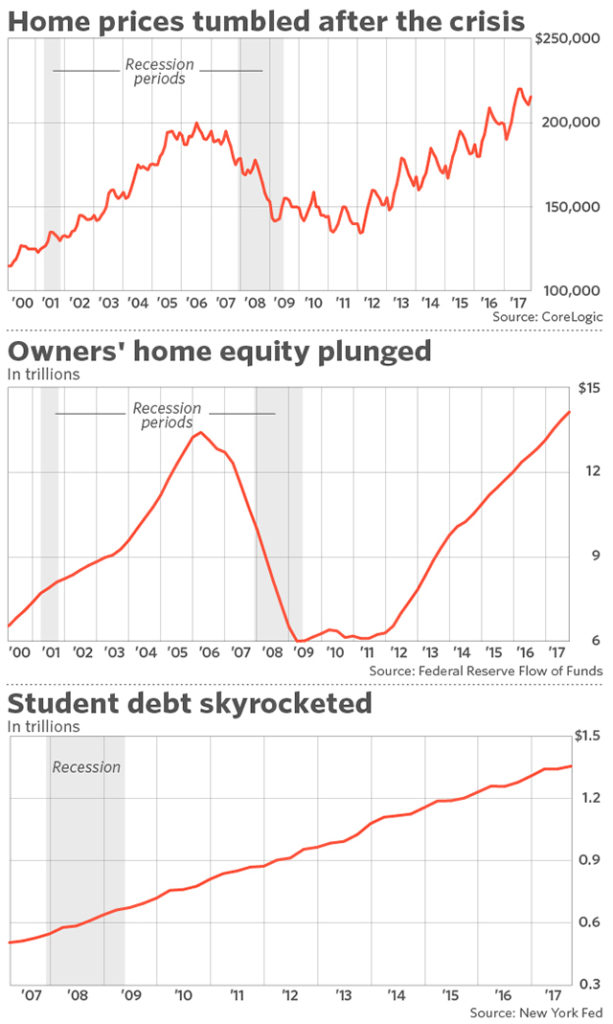

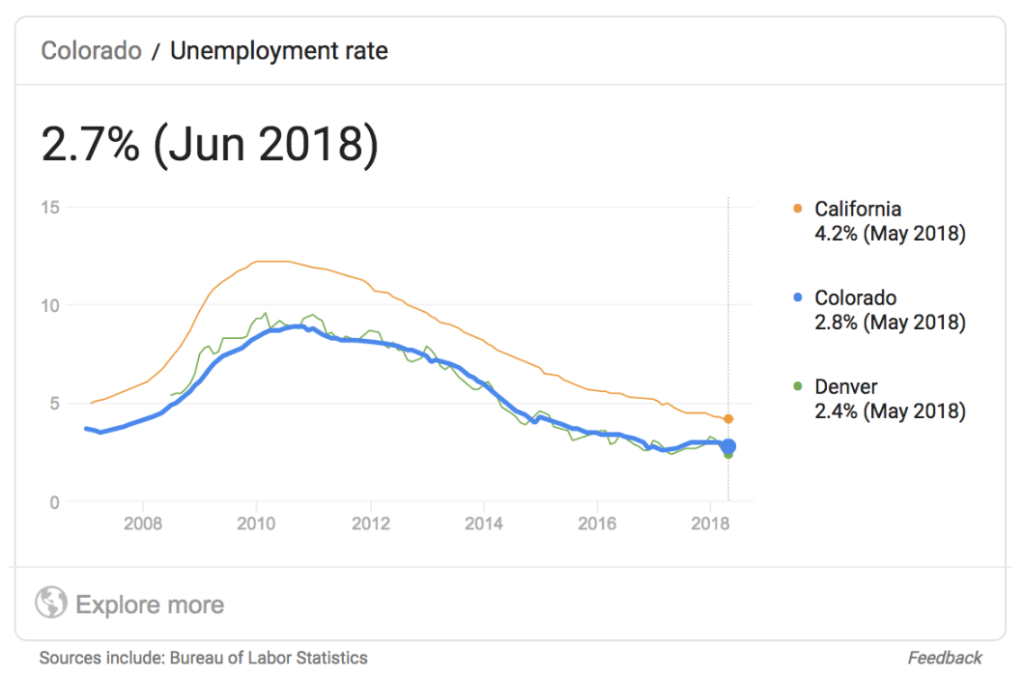

Unmet needs meaning desired services, tangible inventions and reforms to existing systems. Openings of new businesses and corporations also mean that there are more employment opportunities. Whether the level of entry is high, the industries market will continue to grow and change with an influx of jobs being introduced either way. This is a very positive trend in these metropolitan areas because the demand for jobs, while the price o rent, insurance, tuition, etc. all seem to be increasing as well, therefore unemployment rates have been at a steady decrease since the financial crisis in Colorado.

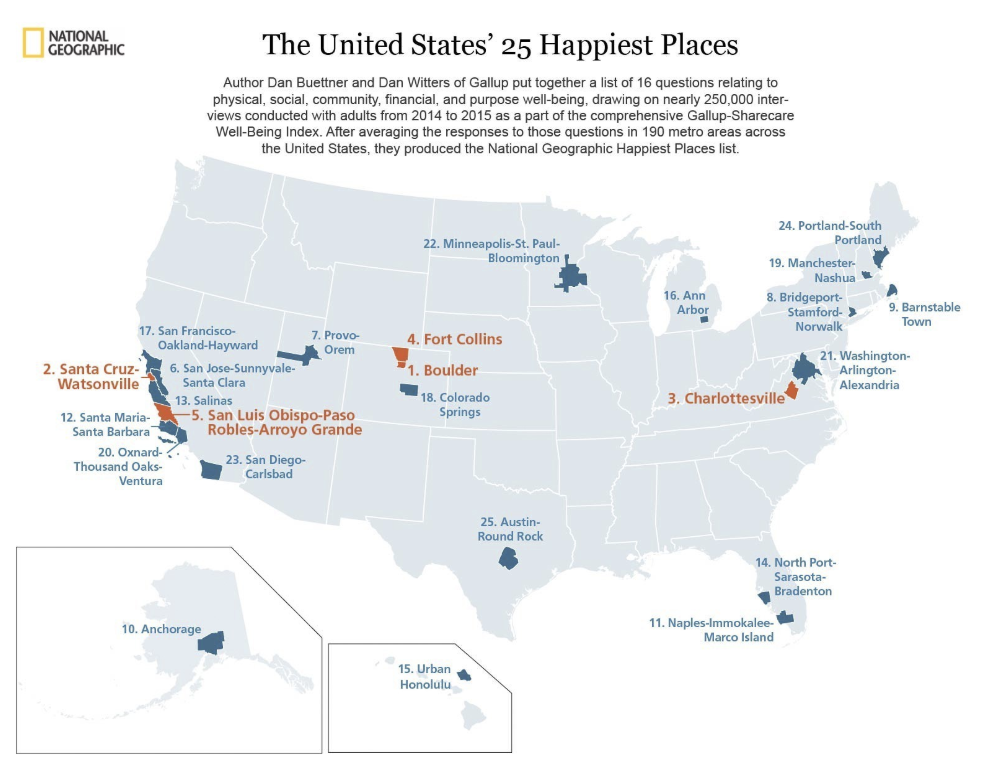

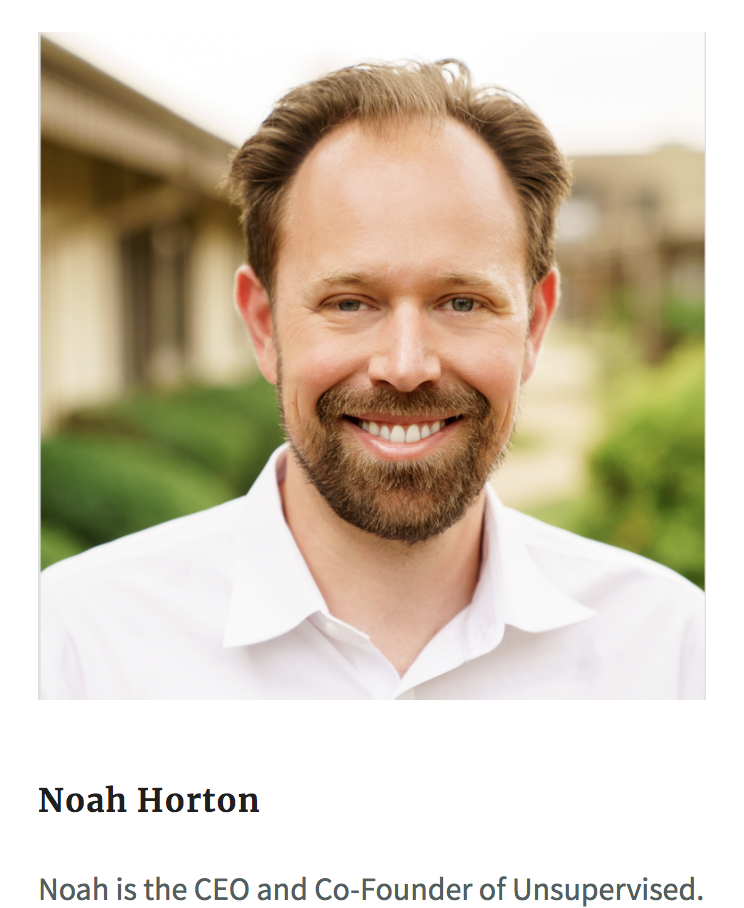

Brad Feld, the author of “Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City and Co-founder,” the co-founder of TechStars and managing director of Foundry Group, a VC fund focused on early-stage investments, developed the concept called the “Boulder Theory.” This theory is based on breaking down the four major com ponents essential to how start-up communications start and evolve. Noah Horton, CEO, and Co-Founder of Unsupervised, an AI data analysis tool that is used to automatically detect trends and draw insights from a companies data in a much shorter time span, spoke with me about his take on the “Boulder Theory.” Horton chose to relocate to Boulder, CO from the infamous Silicon Valley for a better quality of life. In a phone interview with Horton, he said that, “It just makes more sense to save money and live some place where I will be surrounded by nature and still be able to find incredible talent to come work with us.” Horton has been in Boulder for the past three years and has seen a continual increase in people moving to the city, and finding talent that is leaving the bay area to come to what National Geographic has deemed The Happiest City in the United States.

ponents essential to how start-up communications start and evolve. Noah Horton, CEO, and Co-Founder of Unsupervised, an AI data analysis tool that is used to automatically detect trends and draw insights from a companies data in a much shorter time span, spoke with me about his take on the “Boulder Theory.” Horton chose to relocate to Boulder, CO from the infamous Silicon Valley for a better quality of life. In a phone interview with Horton, he said that, “It just makes more sense to save money and live some place where I will be surrounded by nature and still be able to find incredible talent to come work with us.” Horton has been in Boulder for the past three years and has seen a continual increase in people moving to the city, and finding talent that is leaving the bay area to come to what National Geographic has deemed The Happiest City in the United States.

Commerce and regional economic integration.

What is important to note is that emerging tech and transportation make it possible for small businesses to export and do business on a national and global scale. Therefore working in cities that are not coastal or main financial hubs, make it possible to still be successful. The selling of local goods contributes directly to that particular region’s earnings and productivity which strengthens the economy and supports the ecosystem and local economy. Having increased investment and entrepreneurial activity is extremely beneficial for an interconnected global economy. The trend of starting new businesses and endeavors in a city gives hope, inspiration and motivation to people living in the city to conceptualize the new sense of opportunity in their area. Entrepreneurs finding solutions to market needs and providing new goods and services proves that cities throughout the United States are capable of pursuing similar endeavors that will enrich their local and the nation’s economy. Articles and lists have been published regularly as well highlighting Colorado’s success in businesses thus far. Built in Colorado focused on promoting the “Top 50 start-ups in Colorado” with the first five companies including autonomous vehicle engineers, educational technology, security data analysis, and a virtual reality house realtor, so you can walk through a house without making an appointment to physically go there. These are just some examples in which the city is advancing and growing their infrastructure.

The proof of growth

What makes projects and change like this so exciting in a city, is that this does not mean that Silicon Valley and New York City are ever going to go away. What this now means is that you do not have to pay to live in one of those cities to have a successful and well-paying job at one of the same companies, there are growing businesses and tech start-ups that are fostering the same environment as they would in any other city. According to BuiltInColorado tech companies in Colorado raised $780 million in funding in 2017 and $35 billion in exits alone in that year. The volume of capital raised is significantly small in comparison to New York raising $4.227 billion in funding during the third quarter of 2017 and the Bay Area raising $4.117 billion as well during that quarter in local start-ups. But, having $35 billion in exits alone means that outside investors are willing to invest and foster the growth of companies out of Colorado because a are aquiring majority of them. In 2017 alone, tech companies, according to CompTIA, made up “9.7% of the workforce in Colorado and contributed $43.4 billion to Colorado’s economy, representing a 14% share in the state’s total economic landscape.” These statistics provide the city with quantitative reason to believe that this direction of Colorado’s investments in start-up culture is benefitting the economy in a positive manner. Honing the ability to create a template or potentially franchisable ideologies and systems to support similar growth in cities across the United States could have a very positive effect on the nation’s economy overall.

Sources:

https://www.cyberstates.org/pdf/CompTIA_Cyberstates_2018.pdf

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/destinations/north-america/united-states/colorado/happiest-city-united-states-boulder-colorado-2017/

https://unsupervised.com/team/

https://www.businessinsider.com/new-york-beat-out-san-francisco-as-a-venture-capital-powerhouse-2017-10

https://www.inc.com/magazine/201312/boulder-colorado-fast-growing-business.html

https://powderkeg.com/the-denver-boulder-startup-scene-a-guide-to-the-front-ranges-givefirst-tech-cultur

https://www.builtincolorado.com/

https://www.builtincolorado.com/2017/10/24/top-100-digital-companies-colorado-2017