A nomadic herder rides past a traditional ger in Northern Mongolia.

Traveling outside of Mongolia’s only major city, Ulaanbaatar, can seem like traveling back in time 800 years. Among the hundreds of miles of rolling hills, I was hard-pressed to find any permanent, man-made structure. It was a natural landscape so untouched by modern man that I half expected to see Genghis Khan’s enormous army thunder down a hill aboard hardy little ponies.

Nomadic herding culture has been a part of Mongolia for thousands of years and it remains a major part of Mongolian life. However, Mongolia’s economy is undergoing massive transformation that could change both the cultural and natural landscape forever.

From 2009 to 2013, the Mongolian GDP nearly tripled in size from a scant $4.584 billion (US) to $12.582 billion, according to the World Bank.

Mongolia’s explosive rise in the Asian sphere began in the late 1990s when Mongolia found itself to be, quite literally, sitting on top of a gold mine. More important than the gold mine, however, was a copper mine, one of the largest in the world, that was buried underground, just north of the Gobi Desert.

Combining lush national resources and its location just north of resource-hungry China, Mongolia was set to launch itself from rural nomadic countryside to industrialized nation within a span of a few years.

Throughout its expedited transition from a largely agricultural economy to an economy in which one fifth of GDP relies on the mining sector, Mongolia has struggled to strike a balance between rapid growth and growth that is sustainable, fair, and environmentally responsible.

Today, the mining industry makes up 20 percent of Monglia’s GDP. This makes the Mongolian economy somewhat reliant on fluctuating commodity pricing as it sells its copper, gold, and other earth minerals to China. It is possible, however, that mining’s share of the GDP is much higher but the Mongolian government is presenting its nation as a well diversified and therefore more stable economy for investment.

Even at 20 percent of the economy, if metal and earth mineral prices plummet, as they did in the second quarter of 2012, GDP growth can halt or even contract without other industries to offset decreased revenue.

Since the beginning of development at the Oyu Tolgoi mine, a major contributor to GDP growth, GDP per capita has grown over 800 percent. However, the Gini Coefficient, a measure of income distributions in which a value of 0 represents perfect equality and 100 represents absolute inequality, Mongolia is rated a 36.5.

This rating ranks Mongolia 70th in terms of equality among nations worldwide. To put this in perspective, the most equal country is Ukraine with a score of 24.8 and the second most unequal country is South Africa, a nation that is still suffering great disparity along racial lines as an aftereffect of apartheid, with a score of 65.

While not nearly as bas as South Africa, nowhere is the disparity of development in Mongolia better illustrated than in Ulanbataar. In the center of downtown lies the massive Chinggis Square, named after the nation’s hero, Genghis Khan. On one end of the square sits the Blue Sky Building. This $200 million project is a glass and steel office building and hotel reaching 344 ft. high which would not look out of place in London, New York, or Shanghai. From this vantage point, the city skyline is dominated with towering cranes building offices, apartments, and shopping centers.

Construction on the Blue Sky Building in Ulaanbataar before the hotel and office building opened in 2009.

A mere 15-minute drive away from the downtown area is a very different sight. On the outskirts of the city an estimated 800,000 former nomads have settled in their gers, traditional felt tents that have been used by nomads for centuries. Here, there is no plumbing, running water, or civil services like trash collection. Some estimates place unemployment in these ger districts as high as 60% and without their herds to support them, many are likely living in poverty.

The story of Mongolia’s rise from uniform underdevelopment to the state of Ulanbataar today began in 1997, when the democratic government, established after the fall of the Soviet Union, which maintained Mongolia as a buffer against China, passed the Minerals Law of Mongolia. This law established the state’s ownership of all mineral resources within its borders and reserved the right to sell mining and exploration licenses.

The goal of this law was to grow Mongolia’s economy after a dip that left their GDP below the billion-dollar mark from 1993 to 1994. If the government could sell its mining and mineral exploration rights to international mining corporations, it could, in theory, increase levels of foreign direct investment, lower unemployment, and raise GDP.

Investors found abundant Mongolian reserves of copper, gold, fluorspar, and uranium highly attractive. In addition to owning natural resources, Mongolia shares a border with China, the world’s largest importer of raw materials. This presents a lucrative opportunity to sell materials to China at a lower price by minimizing transportation costs that make metals and minerals from South America more expensive.

Combining natural resources with its proximity to China, a country that imported $25.1 billion in refined copper and $63.9 billion in gold in 2014, Mongolia looked like the world’s premier destination for mining operations.

Turquoise Hill Resources Ltd., a subsidiary of the Canadian Ivanhoe Mines, found a massive copper reserve in southern Mongolia. It announced a $4.4 billion investment in underground development at its mining sight Oyu Tolgoi on December 14, 2015. Estimated to be the world’s third largest reserve of copper, Turquoise Hill originally invested $6.2 billion in 2013, after years of exploration and analysis, to begin production.

Turquoise Hill Resources has invested over $10 billion so far in the Oyu Tolgoi mine and surrounding infrastructure.

These investments were massive in communities where wealth was generally measured by herd population rather than hard currency. The influx of capital and demand for labor encouraged many nomads to abandon traditional herding practices in order to work for mining companies or construction companies which were needed to build infrastructure like roads and bridges virtually from the ground up.

In order to include Mongolian interests in mining decision-making, the Mongolian government and Turquoise Hill spent five years negotiating the Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement. The agreement states that the Mongolian nation has a 34 percent equity stake in the mine with the ability to renegotiate their ownership to 50 percent as soon as initial investments have been recuperated. This clause is very favorable for mining companies which are essentially guaranteed the recuperation of their investments.

Additionally, the agreement holds the investor accountable for regional economic development, adhering to national and international environmental standards, contributing to national infrastructure, maintaining a workforce that employs mostly Mongolians, and investment in the education of the Mongolian people.

While these terms are written into the official contracts, there is little evidence to support the clauses did anything more than pay lip service to ideas of sustainable development.

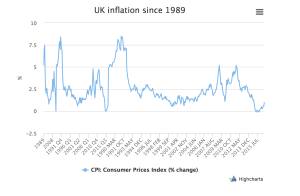

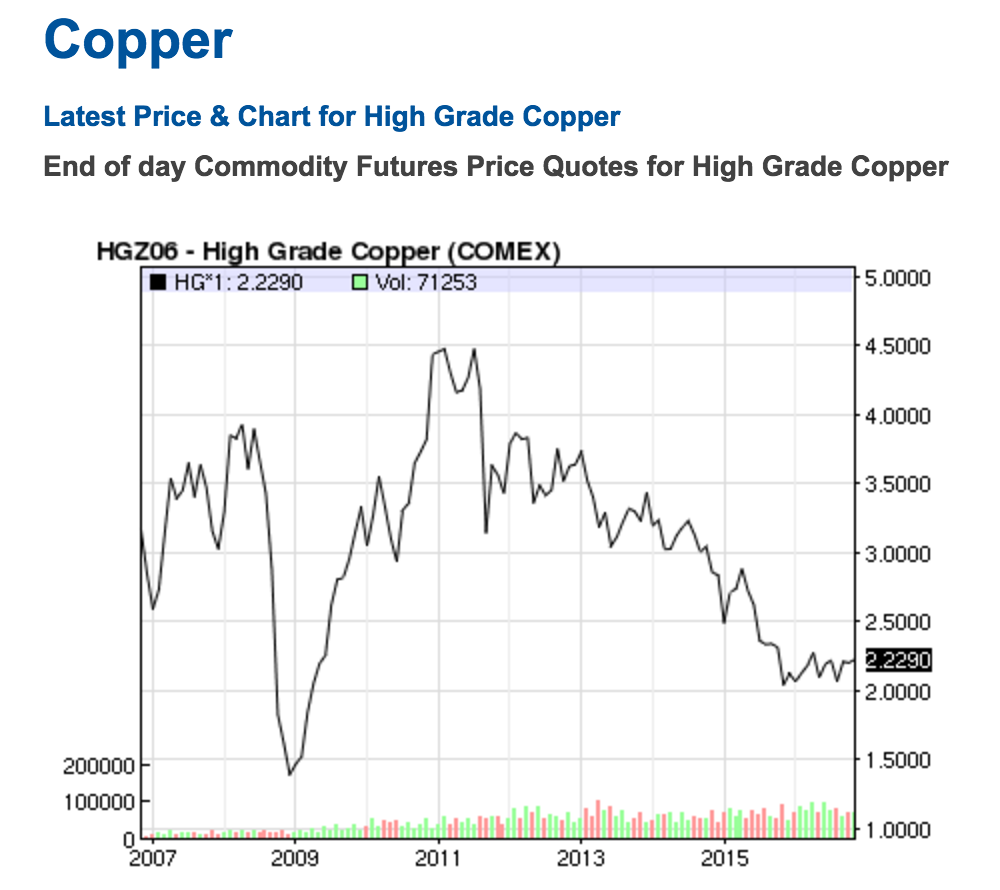

With the volatility of commodity pricing, those who have sold all of their herds and bet on Mongolia’s industrialized future by settling in cities are facing just as much if not more uncertainty than their countrymen and women who remain herders. Over the past five years, copper prices have fallen over 50 percent affecting both wages and unemployment.

After a severe dip in prices following the global economic crash in 2008, copper prices rose. Since 2012, prices have been decreasing.

Dwindling copper prices have slowed economic growth to a crawl, the World Bank predicts 0.8 percent growth rate in 2016, and the Mongolian currency, the togrog, has plummeted in value.

Many economists blame Mongolia’s economic downturn on changes in the slowing Chinese economy. China, which is the destination of 80 percent of Mongolia’s exports, has decreased its demand for commodities like copper and coal, which has driven down international commodity prices significantly. This serves as a double blow to the Mongolian economy because China is not buying as much and prices are falling in the international marketplace.

Despite contractions in copper prices and resulting economic uncertainty, many nomads continue to settle in cities either to seek economic opportunity or escape the uncertainty of harsh winters that can wipe out an entire family’s herd, a Mongolian’s source of wealth and survival. The increasing frequency of these unusually cold winters are intensifying movement to urban areas, as herds die off on the ice covered steppes. These extreme weather conditions have been attributed to pollution and its affects on climate change.

Just like in Ulanbataar, families who renounce their nomadic lifestyles settle in gers on the outskirts of mining towns. During the winter months, when low temperatures average around -28 degrees Fahrenheit, former nomads burn massive amounts coal to keep warm and cook. Air pollution is so bad in the colder months that it exceeds the World Health Organization’s most lenient standards by 600 to 700 percent.

This creates a spiral of urbanization. As more nomadic families leave the countryside and gather in mining towns and cities, pollution increases thereby worsening and increasing the frequency of hard winters, forcing more families to trade their herds for mining or manufacturing jobs.

Former nomads settle in their gers near mines to find work.

Former nomads settle in their gers near mines to find work.

What were once seen as beacons of opportunity are now more like poverty traps. Those who work in the mines are either susceptible to injury or the arduous labor prevents many miners from being hired past age 40. Even people who have moved to cities to support the growth of mining towns by opening shops and restaurants are feeling the strain of dwindling copper prices as miners become unemployed and have less to spend. And without the herds of sheep, goats, yaks, and horses that used to sustain Mongolians through the harsh winters, those who can no longer find work will find an economic landscape almost as barren as the Gobi Desert.