Why pay exuberant prices for goods and services when you can rent it more cheaply from a stranger online? That is the principle behind a range of online services that make it possible for people to share accommodation, household appliances, cars, bikes and other items, connecting owners of underused assets with others who are willing to pay for them. A growing number of businesses such as Uber, where people use their car to provide a taxi service to paying passengers, or Airbnb which lets people rent out their spare rooms, act as matchmakers, allocating resources to where they are needed and taking a small percentage in profits in return.

Such peer-to-peer rental business is beneficial for several reasons. Owners make money from underused assets. Airbnb says hosts in San Francisco who rent out their homes average a profit of $440 (after rent) and some neighborhoods snagging upwards of $1900 a month. Car owners who rent their vehicles to others using RelayRides make an average of $250 a month; some make more than $1,000. Borrowers, meanwhile, benefit from the convenience and pay less than they would if they bought the item themselves, or turned to a traditional provider such as a hotel or car-hire firm. And there are environmental benefits, too: renting a car when you need it, rather than owning one, means fewer cars are required and fewer resources must be devoted to making them.

The internet plays a vital role in this business, it makes it cheaper and easier than ever to provide accurate supply and demand information. Smart phones with global tracking services can find a nearby room to rent or car to borrow. Online social networks and review systems help develop trust; internet payment systems can handle the billing. All this lets millions of total strangers rent things to each other. The result is known variously as “collaborative consumption”, the “collaborative economy”, “peer economy”, “access economy” or “sharing economy”.

The model of the sharing economy works for items that are expensive to buy and are widely owned by people who do not make full use of them. Bedrooms and cars are obvious examples but you can also rent fields in Australia, washing machines in France and camping spots in Sweden. As proponents of the sharing economy likes to put it, access trumps ownership.

How Did We Get Here and Why Now?

The world is at a turning point. Globally, economies are strained as companies and governments are seeking to “do more with less”. Natural resources are no longer cheap and plentiful and some are at the risk of exhaustion. The urbanization of populations continues to rise, and more old people are ageing while young people, such as the Millennials also known as generation Y, are booming. These changes are most prevalent in big cities and new business have already begun to adapt.

The consumer is changing, the Millennials generation, born 1980s to early 2000s, are 92 million strong and stand to inherit large amounts of wealth and decision making power in the U.S. for many years to come. Millennials have experience incredible uncertainty, having lived through the 2008 – 2009 financial crisis and struggles with increasing student debt. These financial pressures lead to demand for a more efficient allocation of resources – and that, by large means they want to own less, be more connected with others and be a part of something bigger than their individual selves.

While the classic American dream is to own everything, the Millennial’s version is to move to an “asset light” lifestyle. These trends have sparked massive innovation, created new marketplaces and potentially holding the keys to the future.

Premium on Ownership Disappears

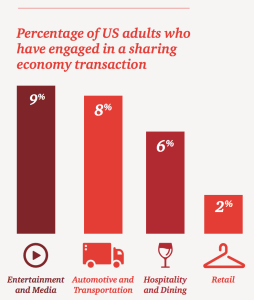

About a decade ago, companies such as Zipcar started to capitalize on idling cars, which sit on idle for an average of 23 hours a day. Today there are hundreds of ways to share assets, the most popular ones include entertainment, transportation and hospitality and dining.

At 9% entertainment and media holds the highest percentage of users. The consumption of media has changed drastically since the rise of digital age and perhaps it is the best example of the millennial  generation shift.

generation shift.

Let’s travel back to 1999, when the millennials were still children exploring the internet. Many children took advantage of Napster, a website that enabled users to download songs for free. Illegal? Sure. But no one really cared. There are profound differences between the millennial’s peer-to-peer downloading than that of their parents or even people 5 years their senior. From the very beginning the experience of acquiring and consuming media content was based on the premise that access to content should be easy and free.

Now back to 2015, access to media content is essentially free. Want on-demand access to whatever music you want? Spotify has got you covered. On-demand access to movies and TV shows? Netflix. On-demand access to videos of anything you want to watch? Lose a few hours on Youtube. Of course some of these services require a subscription fee so they are not truly free. But when access to goods and services becomes cheap, satisfactory and reliable enough that the premium on physical ownership has disappeared, there is hardly any reason to purchase these goods and services aside from personal habits or peculiar requirements.

Ten years ago, to watch a movie released on DVD, there were 2 options: purchasing or renting. Of those options, renting was the inferior option as there was a greater premium on ownership. Today, that premium has disappeared, streaming a movie on Netflix isn’t inferior to owning a DVD the same way that renting was. And ever since then, the extensive access to cheap and easy media content, has lead to new kinds of behaviours have emerged like binge-watching. Similarly, the rise of music streaming services has enabled behaviours such as sharing playlist, a process that used to be time-consuming and effort-intensive. When nobody buys music but has access to it, social sharing of music emerges as a natural and human behaviour.

Obstacles on the road to Success

To truly grasp the scale and greatness of the sharing economy, consider the following data. Airbnb averages 425,000 guests per night, totalling to more than 155 million guest stays annually – nearly 22% more than Hilton Worldwide, which serves 127 million guests in 2014. Five-year old Uber operates in more than 250 cities worldwide and as of February 2015 was valued at $41 billion – a figure that exceeds the market capitalization of companies such as American Airlines and United Continental. According to PwC’s projections, the sharing economy (including travel, car sharing, finance, staffing and music streaming) has the ability to increase global revenues from $15 billion today to around $335 billion by 2025.

It is not hard to find evidence of successful sharing economy but not everyone is as delighted by the rise as its participants and investors. Taxi drivers in America and now Europe have complained loudly (and in the case of Paris, violently) about the intruders who, they say not only are unqualified but also under insured.

Uber has always been plagued with problems with regulation and taxi unions around the world. In 2014, a court in Brussels prohibited drivers from from accepting passengers through UberPOP or face a €10,000 fine. In July 2015, Uber took one of its biggest hits. The judge ruled that Uber has not complied with state laws designed to ensure that drivers are doling out rides fairly to all passengers, regardless of where they live or who they are. This lead to a $7.3 million fine or California Suspension.

It is not just car-sharing services that have run into legal problems. Apartment-sharing services have also fallen victims of regulations and other rules governing temporary rentals. Many American cities ban rentals of less than 30 days in properties that have not been licensed and inspected. Some Airbnb renters have been served with eviction notices by landlords for renting their apartments in violation of their leases. In Amsterdam, city officials point out that anyone letting a room or apartment is required to have a permit and to obey other rules. They have used Airbnb’s website to track down illegal rentals.

On top of legal regulations, issues with customers have also become obstacles for sharing businesses. In 2011, Airbnb suffered a rash of bad publicity when a host found her apartment trashed and her valuables stollen after a rental. After some public relations and Airbnb eventually covered her expenses and included a $50,000 guarantee for hosts against property and furniture damage.

Peering into the Future

The sharing economy can be compared to online shopping, which began in America 15 years ago. In the beginning, people were not too sure about the vendors and didn’t trust the services. However with time and perhaps a successful purchase on amazon or two, people felt safe buying from other vendors too. Now consider Ebay, a company started as a peer-to-peer platform, now is now dominated by professional “power sellers” (many of whom started as ordinary Ebay users).

Big corporate companies dominating the market are getting involved too. Avis, a car rental firm has shares in Zipcar, its car sharing rival. So do GM and Daimler, two car manufacturers. In the future, companies may follow a hybrid business model, listing excess capacity on peer to peer websites. In the past, new ways of doing things online have put the old ways out of business. But they have often changed them.

We will have to wait and see which on-demand services start to gain traction with mainstream markets and which wont’t. It is not likely that in thirty years time our whole lives will be on demand and we won’t hold ownership. But a major possibility is products and industries most likely to be disrupted by the sharing economy would be things that we possess but not necessarily. An example would be Airbnb, it has disrupted the demand for owning vacation homes (something you possess) and tourist hotels (something you don’t possess but is still “yours” in a way that an Airbnb isn’t).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.