The airline industry has an image problem. Plagued by delays, lost bags, impossibly small seats and high ticket prices, flying has become almost synonymous with discomfort, stress, and expense. Indeed, the industry has long been hindered by fundamental problems: sky-high operating costs, spikes in the price of jet fuel, cut-throat competition, and a loss of consumer goodwill. But while the aviator and concorde-filled glory days of air travel are certainly a thing of the past, the industry is undergoing significant changes and an upswing which serves to benefit everyone from passenger to pilot.

Historically, airlines have long-struggled to balance their costs and profits while maintaining passenger satisfaction. In 2012, the industry made an aggregate profit of just $7.6 billion on revenues of $638 billion, a meagre 1.2% net profit margin, according to the International Air Transport Association’s Annual Report. Of the other 98.8%, over two-thirds goes to the airlines’ fixed costs. Of these, labour and jet fuel make up almost half of operating expenses, with the price of jet fuel alone more than doubling in the last decade (See Graphic I).

Graphic I: The price of jet fuel alone has more than doubled in the last decade

In addition to the industry’s inescapable dependence on the fuel, the price of jet fuel rises and falls almost in tandem with that of crude oil, making it highly susceptible to shifts in global politics. Strong industry-wide unions resistant to technological automation prevent airlines from laying off staff. Finally, cut-throat competition complemented by the advent of price comparison sites like Kayak and Expedia have created broader awareness and price sensitivity in the marketplace. Even with these heightened costs, airlines have been unable to raise prices or work to distinguish themselves to gain more market share due to mounting and inescapable financial obligations. As a result, all of these costs have often translated directly to the airlines’ bottom lines.

Sites like Kayak.com and Expedia have made consumers more sensitive of ticket prices

“That airlines made any money at all [in 2012] with GDP growth at 2.1% and oil averaging a record high of $111.8 a barrel was a major achievement,” says Director and CEO of the International Air Transport Association (IATA) Tony Tyler in the industry association’s annual report.

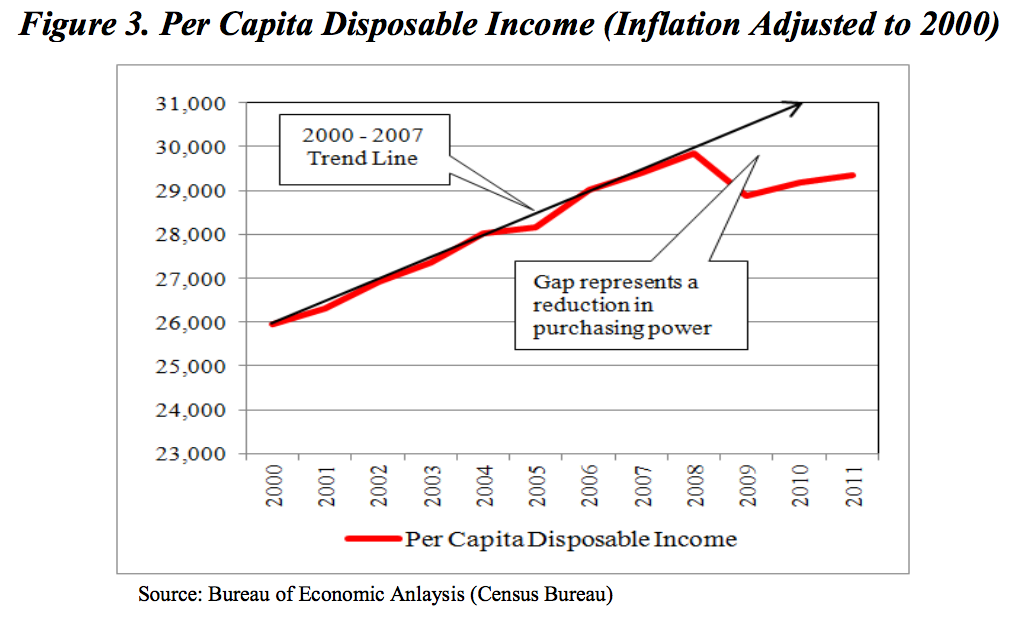

Indeed, despite seemingly insurmountable challenges, the airline industry has shown remarkable robustness in fulfilling its role. During the recession, the airlines saw the first decline in passenger numbers since the decreases caused by September 11th. Even with lowered fuel costs, reduced per capita disposable income and economic activity reduced the demand for air travel (See Graphic II). In the aftermath of the recession however, the airlines have worked hard to dramatically consolidated, trimmed, and altered the industry.

In the U.S. market, the major airlines have consolidated and transformed control of the industry. According to a review of the aviation industry by the Office of the Inspector General, of the ten major American airlines controlling 90% of market share in 2009, just five in 2012 (and now four) remain in the market with a share of 85% of domestic passengers. Through such mergers, the major carriers have been able to strengthen their market position and cut costs, reducing price wars and allowing them to get away with charging new service fees. In 2013, the major U.S. carriers racked up more than $6 billion as part of these new ancillary fees. These fees aside, merger-driven consolidation of the major airlines together with the continued growth of low-cost carriers like SouthWest and JetBlue continues to stimulate essential competition between airlines.

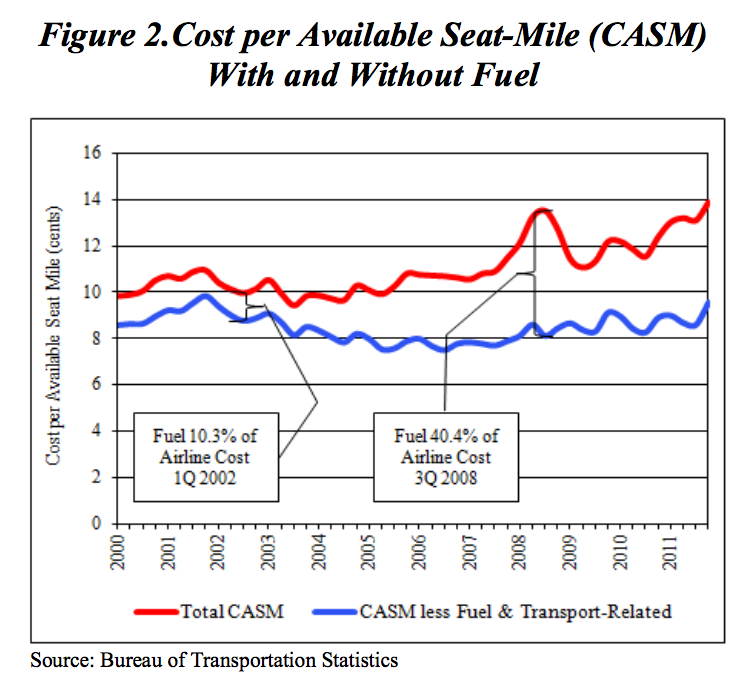

Key to their increased profitability, airlines across the board have succeeded in improving their efficiency. According to a PWC industry trend report, the airlines significantly advanced their capacity discipline, or load factor. Since 2008 there has been an 8% reduction in the number of flights, but just a 1% reduction in number of passengers. More tellingly, though the price of jet fuel now approaches that of its 2008 peak, the airlines have maintained a non-fuel operating cost close to previous levels despite rising costs in fuel. So though the total cost per available seat-mile (CASM) has grown, for example, most of the increase is derived from rising fuel costs (See Graphic III).

In spite of these efficiencies, airline expenses remain high. The rising cost of maintenance, higher salaries (demanded by unions as part of merger negotiations), and environmental taxes contributed to a decline in the average industry operating income per seat-mile of 0.28¢ in 2012. But overall confidence in the airline industry is up. Air freight, an important industry indicator that underwent a significant decline in the last three years, is expected to see growth of 4% in 2014 according to an industry outlook report. Airlines will also see long-terms gains as a new, more fuel-efficient generation of planes is delivered.

Boeing’s new 787 Dreamliner promises increased fuel efficiency and more passenger comfort

How it all affects the traveller remains to be seen. Though industrywide customer satisfaction is on the rise according to the latest American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) report, passengers continue to complain about the actual flying experience. Reduced delays, worldwide alliances and loyalty programs, as well as more efficiency and stability in the marketplace stands to improve, at least minimally, the traveller’s experience. In changing the way we fly, however, it might be best to look to start looking not at the airlines but the technological manufacturers at Boeing & Airbus et al.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.