Faced with a rapidly changing consumer, the biggest hoteliers are changing their approach. In doing so, however, they threaten to almost entirely alter the hotel industry.

The hotel industry is not usually one known for innovation. In the last 40 years, hoteliers have introduced only minor changes coming few and far apart: Holiday Inn debuted the Double Queen bed room, someone painted a white wall grey, and a few have finally managed to add Wi-Fi. But a new wave of guests, the oft-discussed millennial generation, is demanding a new type of hotel that poses to fundamentally alter the industry. Initially dismissed as outlandish, the boutique hotel model is entering the mainstream, falling into favour with the latte-and-laptop generation over the carbon copy boxes championed by brands like Hilton, InterContinental, and Marriott. But responding to these needs is more than a momentary race for market share. As the big hoteliers move into the boutique game hoping to recapture the modern-day traveller, they are altering the industry at its roots, and perhaps unknowingly, sowing the seeds for a whole new way of doing business in the hotel space.

Traditionally the major players in the hotel industry left innovation to avant-garde boutique hotels. These city-based concepts that rose to prominence in the 1980s were viewed largely as fads. Hotels like the Bedford in San Francisco and The Blakes Hotel in London catered to an insignificant group in search of a sophisticated, unique, and off-beat hotel experience. For these people the boutiques acted as a counterweight to the unchallenged standardisation of the bigger chains. As the New York Times’ David Brooks explains in the The Edamame Economy, “instead of offering familiarity, they offered difference. Instead of offering beige, they offered edginess, art, emotion and a dollop of pretension.”

Avant Garde: Boutique hotels reimagined the guest experience, but most took it too far for the average consumer

Standing strong behind staggering economies of scale and multi-brand loyalty programs, the larger hotel groups did not consider the forward-thinking boutiques a threat. This belief was reinforced as they expanded globally throughout the 1980-90s. The chains employed a growth model that demanded the standardisation and commoditisation of their products, giving rise to what is now known as the ‘box hotel concept.’

Not exactly something to rave about: Box-like hotels offering a consistent and uniform experience can be found all over the world

All around the world, hoteliers adhere to cookie-cutter methods that centre on a number of familiar core products and capabilities. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) delineate exactly how hotel staff must behave to maintain the brand’s image. A 2010 Hilton manual outlines how a caller’s name must be used twice during a call. Housekeeping staff at Marriott famously follow a 66-point checklist for guest room servicing and ensure the sheets in Kuala Lumpur have same specified thread-count as those used in London.

While the consistency of these brands is a remarkable accomplishment, the ‘McDonaldisation’ of the hotel experience has made the experience what The Economist calls an “emotional failure.” Inherently, the model continues to see economic success due to its established reliability and worldwide network. After all, the familiar red Marriott logo remains one of the surest signs of comfort and a decent night’s sleep. Undeniably however, there is a growing segment of travellers looking for more. Currently only serviced by boutique hotels, more and more big hoteliers are looking to tap into this market of affluent, trendsetting travellers.

The Modern Guest

As the larger hotels look to the boutiques for their pioneering insight, the greatest difference is surely the type of guest. The modern traveller, who is as likely to step out of a sleek black Uber wearing a tailored suit as arrive in a t-shirt and jeans after using the Tube, is one of the most significant changes in the hotel industry’s recent history.

Unpredictable: The millennial generation is one less characterised by age than by style, interest, and diversity.

“Guests used to come for one of two things: business or pleasure,” says Patrick Tan, a student at Cornell and front-office supervisor at the school’s esteemed Statler Hotel. “Now it’s a mix of work and play that involves everything from business meetings and art gallery visits to city tours to drinks at the city’s best bars”

Tan’s statement is supported by market research. A 2013 survey conducted by a Hilton Garden Inns saw 45% of respondents cite new experiences as the best part of business travel. For 65% of the survey-takers exploring a new city was the number one motivator to extend a business trip.

More than ever before, the hotel guest has transcended the confines of their hotel. Keen to explore, curious, social, and often combining work and weekend trips, the modern traveller and guest no longer looks for the uniformity offered by the larger business chains.

“People are seeking unique experiences. They are seeking hotels that are distinctive from others in style, design and service.” writes Veronica Waltdhausen in a study for leading Hospitality Consultants HVS.

In the golden age of hotels, people came to be pampered and surrounded themselves with luxury. It was under this model that the star system, where the number of stars equates to higher price point, came into being. But the modern-day traveller is no longer looking for a money-driven experience. Instead of status symbols they seek experiences.

“Do they really want a Nespresso machine in their room (the proud new addition to most hotel rooms),” Waldthousen asks. “Wouldn’t a guest be much more likely to relax in a bar in the hotel’s lobby lounge and drink a coffee surrounded by other people?”

This movement away from the tangible product to an experiential one is complemented by a change in what millennial consumers look for in hotels. Rooms at CitizenM, the contemporary Dutch hotelier that was one of the first players to act on these new demands, feature plush beds, high-powered rain-showers, and free WiFi and movies. Advertisements for the hotel, however, centre on the actual guest experience, highlighting “a great night’s sleep” and “a love for free movies on demand.”

The lobby of CitizenM’s Bankside property in London features contemporary art and furniture, a happening bar-scene, and some of the capital’s coolest meeting spaces

The company’s mantra – affordable luxury for the people – does away with unnecessary luxuries over which many hotels compete. The hotel’s lobby swapped out doormen and luggage carts, favouring automated check-in kiosks that set room temperature and mood lighting to a personalised preference upon a guest’s arrival. A buzzing bar and eatery is complemented by sharp but inviting italian furniture, contemporary art and books, as well as dynamic meeting spaces right off the lobby-floor.

“The lobby is more like a living room than anything else,” says Noreen Chadha, CitizenM’s Commercial Director. “The room is the place to sleep and relax while the lobby is the perfect place to work, meet, eat, and drink.”

As Chadha explains, the physical boundaries that once distinguished hotel lobbies, bars, and restaurants are blending together. The open-space lobbies of hotels like CitizenM or the Ace Hotel simultaneously entertain an array of work meetings, lunch dates, happy hours, and even musical performances. For the hotels, the lobby’s transformation works to bring in both guests and city residents. Whereas the typical hotel bar and restaurant sits mostly empty, these venues hum and buzz, drawing in both the hotel guests and local crowds. For these kinds of hotels, the restaurant can move from being a money-losing nicety to a key asset. According to a Business Journals report, hotels that share their vision and values with restaurants can see up to 20% of revenues coming from food and beverage operations.

The hotels also benefit by being able to generate more revenue per square foot. While the larger corporate hotels may have higher occupancy levels and even feature several restaurants, a comparably-priced boutique hotel that optimises its space and plays host to more guests and visitors in its bar, restaurant, or lobby will have greater revenue per square footage. So while it is difficult to make an apples-to-apples comparison, the boutique model almost certainly presents a better deal.

Historically, the big hoteliers looked on passively on from the sidelines. Business guests and foreign tourists built work trips and holidays around the reliable and consistent nature of the big chains. From Caracas to Mumbai, a Hilton was a Hilton.

But as the millennial generation approaches its peak, a new type of guest is emerging. No longer impressed by turn-down service and trouser presses, they seek unique experiences and interactions. Generation X and Y already make up more than 50% of hotel bookings. And with the boutique industry expected to increase at 6.5% annual rate between 2014 and 2019 according to an IBIS World report, each of the major chains is now keen to capitalise on this growing industry.

Bringing in the Big Boys

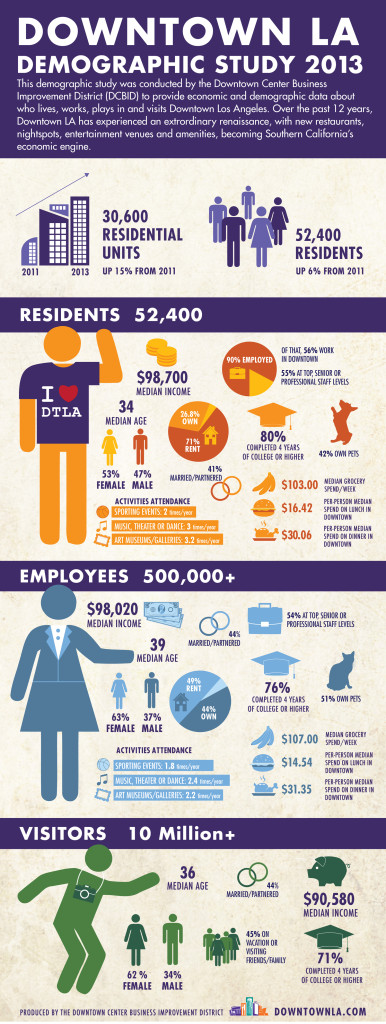

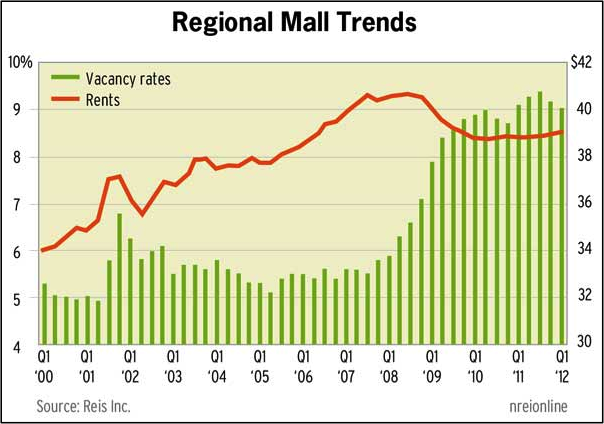

With the hospitality industry continuing its post-recession recovery, the large hoteliers are looking to diversify their portfolios. Though boutique hotels took a 12.7% hit in 2009 with revenue per available room (RevPAR) falling as much as 30%, the segment typically yields high profit margins. During times of economic upswing, boutique hotels are more attractive than ever. Generally low-cost investments, they attract an affluent customer and offer an exciting opportunity for brand building. Among the hotel industry’s largest operators, these projects are being fast-tracked by forecasts about the vastly different needs of the rapidly expanding millennial segment.

Besides the substantial research pointing to the millennial opportunity, one of the industry’s largest players, Starwood, is already knee-deep in the boutique world. The company, whose 10-brand portfolio demands about 12% market share in the boutique industry according to IBIS World, owns some of the industry’s leading names. Its W, Aloft, and Element hotels and franchises have proved to be “game-changing” for the company and continue to lead and “disrupt” their respective industries, according to Starwood’s 2012 report. In each market, these Specialty Select Brands (SSBs) continue to drive growth*. In Canada, the hotelier’s Element brand debuted just last year but has already overtaken its competitors on the popular comparison website TripAdvisor.

Early Adopters: W Hotels have brought the boutique model to a global audience

Given Starwood’s demonstrated track-record, more and more of the major players are launching brands into the space. Next year, Marriott will debut its Moxy brand in partnership with the Swedish design giant, IKEA. Despite it being the world’s largest hotelier’s first foray into the millennial space, the hotels feature a now-familiar model of design, approachability, and affordability. By a similar token, the parent of the normally no-frills Radisson brand plans to spend $140 million building or acquiring the first five properties of its new, daring Radisson Red brand. The hotel, which channels the concrete, loft-like feel of a modern art gallery joins Starwood’s Aloft, Hyatt’s Andaz, and InterContinental’s Hotel Indigo brands .

Carlson Redizor’s new Radisson Red concept brings a boutique-element to its normally no-frills approach

It goes without saying that the entry of the larger players has dramatically increased the size of the boutique industry. As explained by IBIS World, the industry is “on its way up to the penthouse,” with industry growth expected to surpass pre-recession levels before 2019. Fielding heightened demand from a 3.1% and 2.7% annualised increase in the number of international arrivals and domestic trips respectively, hotel operators will see a surge in demand in both domestic as well as foreign markets.

On the rise: Domestic trips and international arrivals are driving up hotel occupancy numbers

A Boutique Bubble?

While the numbers point to a triumphant ‘go,’ questions remain about the viability of this new model. For one it seems as though both boutique and big brands occasionally lose sight of the purpose of this modernisation. From a literal standpoint, critics of Marriott’s upcoming Moxy brand claim the brand’s fast-paced rollout – which hopes to build 150 Moxy hotels in Europe over the next 10 years – may be too ambitious. Others cite the location of its first property next to Milan’s Malpensa airport as too far removed for the economically-minded millennial.

In a 2007 article for The Wall Street Journal, Darren Everson highlights some of the industry’s more fundamental issues. Everson sketches the stay of a University of Southern California graduate student staying at the W Chicago City Center hotel, citing confusion and discomfort.

“There is a backlash brewing against boutique hotels,” Everson writes. “[While] W’s are still thriving, the…segment is finding that some customers – even once loyal ones – are getting tired of their tragically hip ways.”

Indeed, as the industry giants skip from baby steps to a full-steam sprint, they risk alienating their newest customer before they even arrive at the hotel’s doorstep. In the age of cut-throat competition and review sites like Hotels.com and TripAdvisor, just a few negative reviews can result in being crossed permanently off the list.

So, while the millennial guest has almost certainly swapped room service and bidets for contemporary design and free Wi-Fi, certain elements remain, and are perhaps more relevant than ever. Though veterans of the old-model, consistency, loyalty incentives, and good service remain at the top of the list for many consumers. The form follows function principle continues to reign supreme (as this author found out when water from his shower spread cooly across the entire bathroom floor at The Standard Hotel).

Form over function: The Standard Hotel in NYC features some of the industry’s coolest, and most inconvenient, designs

For the boutique industry, the entry of everyone from Hyatt to Hilton ushers in an unprecedented era of competition. For the full-line producers however, the move into the boutique space may be the first step to fundamental change the hotel industry as a whole. While currently still limited to one or two brands in the portfolio, the tenets driving the change: change in the core customer, promises to revolutionise the field.

As Jeffrey Catrett points out in his article for Hotel Business Review, similar changes to the retail and other service sectors have forced industry-wide overhaul. For the standardised hotel industry, the costs of changing thousands of properties around the world seems almost unimaginable. The ageing core products of these hotels – behemoth conference spaces, spas, and other amenities – may soon be more or less obsolete. While the luxury segment, particularly resorts, will be sure to carve its own niche, the mainstream hotels may soon face something of a crisis. Indeed, changing consumer trends sometimes stirs trouble. For the hotel industry and the biggest players in particular, however, they just might change the way they do business entirely.

*Starwood’s Annual report does not provide a financial breakdown of each brand, making it difficult to quantify how much each contributes to the company’s overall profitability and growth.

For malls and brick-and-mortar retailers, the emphasis now lies on what Rick Caruso calls the need for “reinvention of the shopping experience.” Rather than be what was once, according to a 1971 news article, a “monument to big spending and the shopping spree,” the modern mall looks to capitalise on a growing demand for experiential shopping.

For malls and brick-and-mortar retailers, the emphasis now lies on what Rick Caruso calls the need for “reinvention of the shopping experience.” Rather than be what was once, according to a 1971 news article, a “monument to big spending and the shopping spree,” the modern mall looks to capitalise on a growing demand for experiential shopping.

Walk into Badmaash and it becomes instantly clear what the brothers are talking about. The familiar overwhelming buffet-style dishes are replaced with portion sized plates paired with a selection of hand-picked artisan beers. The LCDs blaring Bollywood songs are gone, swapped for a cool, silent Indian classic projected on the large wall. A set of Warhol-like portraits of Mahatma Gandhi wearing coloured aviators lines the wall.

Walk into Badmaash and it becomes instantly clear what the brothers are talking about. The familiar overwhelming buffet-style dishes are replaced with portion sized plates paired with a selection of hand-picked artisan beers. The LCDs blaring Bollywood songs are gone, swapped for a cool, silent Indian classic projected on the large wall. A set of Warhol-like portraits of Mahatma Gandhi wearing coloured aviators lines the wall.