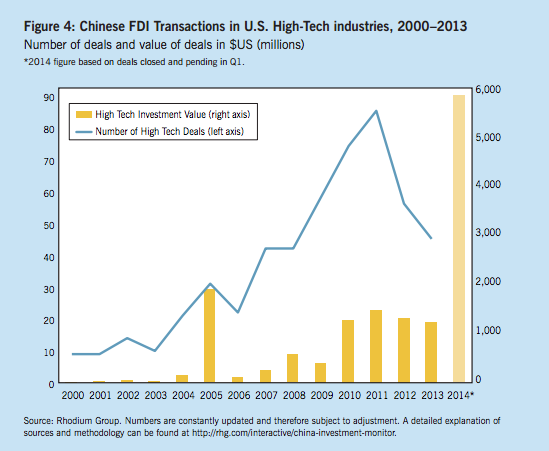

Three months into 2104, Chinese investors announced they’ve snapped high-tech deals worth more than $6 billion in the U.S. The figure, which is greater than the combined total in the past four years, marks a giant leap in high-tech investments made by private companies from China. But instead of welcoming new jobs and R&D grants, business communities across America are advised to be wary of the innocence of Chinese companies.

A recent report published by The Rhodium Group and Asia Society concludes Chinese buyers may have set out to target high-tech industries in the U.S. While the number of deals has dropped since 2011, the value of China-U.S. high-tech transactions took a jump in the first quarter this year. Overall, Chinese direct investment in the U.S. reached a record high of $14.1 billion last year since taking of in 2008, according to the report.

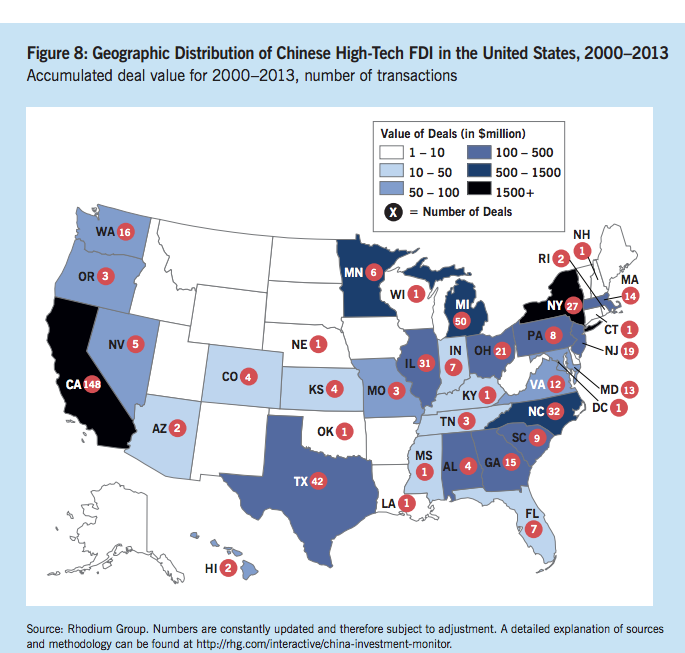

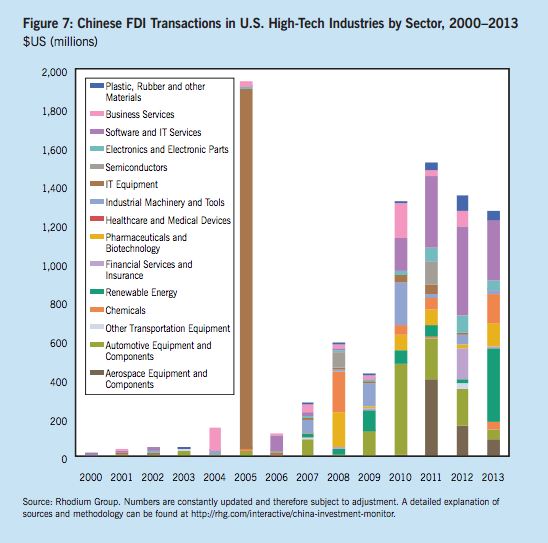

The boom can be seen across America and in a variety of sectors. A majority of Chinese investors, as graphic below shows, unsurprisingly struck deals with technological communities in California. There was a lot of Chinese money going into IT equipment when Chinese PC maker Lenovo bought IBM’s personal computer business in 2005. But the appetite for software and IT services has prominently grown in the past few years.

Setting numbers aside, a primary issue the report addresses is how to react to the rise of Chinese takeover of “valuable” technological brands made in the U.S. At a conference held in L.A. on Thursday, most bankers and lawyers who helped handle high-tech transactions for their Chinese clients in the past voiced their major concerns: American companies should look out for possible technology theft, and the U.S. government should make efforts to beef up cyber security.

The big-ticket sales capture a shift in China’s economic ambition and could be a prelude to the country’s departure from being a global manufacturer. But being on a learning curve doesn’t mean the nation’s transition must be an evil breed. In nature, purchasing IBM’s personal computer business was no different from Facebook’s buying WhatsApp: both indicate the parent company sees some value in the subsidiary, and pays money to learn from it. It is fair bargain as long as both sides shake hands on the price.

The $6-million deals made in the first quarter include three major components: Lenovo, after it purchased IBM’s PC business years ago, is spending another $2.3 billion buying a server unit of IBM. Earlier, it purchased Motorola Mobility from Google for $2.91 billion. China’s Wanxiang Group took in luxury carmaker Fisker in February.

They all have eye-popping price tags, but the health of the three subsidiaries show Chinese buyers are tasked with turning failing American brands around before they move on to harness, if any, new technologies. Fisker had been in huge financial loss and filed for bankruptcy when Asian buyers emerged at the end of last year. Google paid $12.5 billion for the acquisition of Motorola Mobility to obtain the patents it needed to ward off lawsuits from Apple (and they weren’t accused of technology theft), and dumped the “perpetual money-loser” a year later. IBM’s PC unit was, again, losing money when Lenovo bought it in 2005, yet the latter has come back for more. The low-end server business Lenovo is taking from IBM has posted seven quarters of losses.

To the other end, The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) has guarded national security well. It guarded it so well that Chinese telecommunication giants had to shift their U.S. business from installing network equipment to selling smartphones to survive in the U.S. market.

In 2011, Huawei Technologies Co., China’s biggest network equipment maker, was barred from participating in building a nationwide emergency network. A year later, the U.S. House Intelligence Committee chairman discouraged U.S. companies from doing business with Huawei and ZTE Corp, for fear of intellectual-property theft and spying. The Committee also noted in a report that CFIUS “must block acquisitions, takeovers, or mergers involving Huawei and ZTE given the threat to U.S. national security interests.”

From selling handsets, ZTE had a market share of 6 percent in the U.S. last year. The CEO of ZTE’s U.S. division touted the company’s decision to drop network business in the U.S. “a strategic move” and “an adaptation to America’s legal framework.”

The second-largest telecommunication manufacturer in China has opened 14 offices and five R&D centers in the U.S. It hires about 380 local employees. It has invested $350 million in its U.S. business. It remains at the mercy of geopolitics.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.