Edited & Updated

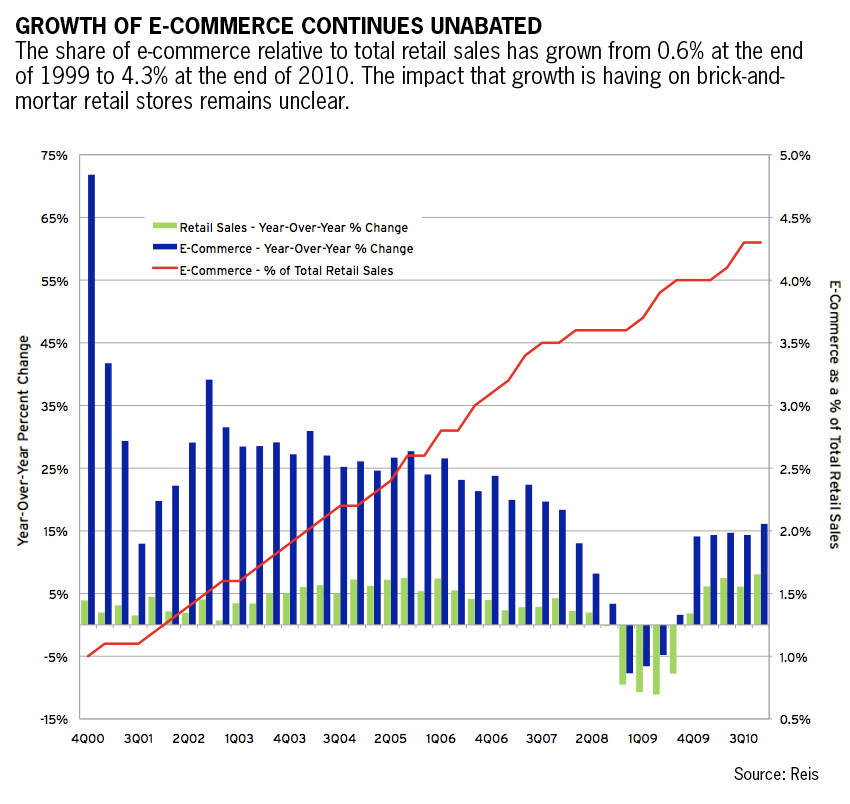

Growing up surrounded by expats in a foreign environment, days at the mall were often a nostalgic subject among my American schoolmates. Indeed, the mall was something of a hallmark for American society to many of us non-Americans. Yet only a few years later, the sprawling shopping centres that were once the favoured activity of families and teens across America, have become relics of a bygone era. Mall mogul and C.E.O. of one of America’s largest privately held real estate companies, Rick Caruso, went so far as to call the traditional mall a “historical anachronism – a sixty-year aberration” that no longer meets the needs of retailers, communities, or the general public. Once known as the ‘temples of consumption,’ the American mall has become outdated and obsolete. Years of haemorrhaging to e-commerce sales has left its mark, driving under anchor retailers and leaving traditional malls increasingly empty. Up from 0.6% in 1999, e-commerce has grown ten times, with sales reaching 6.0% of total retail sales in Q4 2013, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Meanwhile, total retail foot traffic for the key shopping period of November and December saw declines of 28.2% in 2011, 16.3% in 2012, and 14.6% in 2013. Over the same period, online sales increased at more than double the rate of its brick-and-mortar counterpart. As retailers physical sales as a percentage of the revenue stream drop and e-commerce’s market share burgeon at an expected compound annual growth rate of 13.6%, they are faced with a chilling prospect – adapt or perish.

For malls and brick-and-mortar retailers, the emphasis now lies on what Rick Caruso calls the need for “reinvention of the shopping experience.” Rather than be what was once, according to a 1971 news article, a “monument to big spending and the shopping spree,” the modern mall looks to capitalise on a growing demand for experiential shopping.

For malls and brick-and-mortar retailers, the emphasis now lies on what Rick Caruso calls the need for “reinvention of the shopping experience.” Rather than be what was once, according to a 1971 news article, a “monument to big spending and the shopping spree,” the modern mall looks to capitalise on a growing demand for experiential shopping.

“The future of malls is about experience, creating a destination,” says Executive Vice President of Business Development for Mall of America, Maureen Bausch, in an article for Fortune. “It’s about giving the customer an experience they’ll leave their laptop for.” In response to the rising threat posed by e-commerce and declining foot-traffic, real-estate investors and retailers alike have grudgingly initiated plans for the costly redesign and rebuilding of malls across the country. The vision: expand the massive structures to become lifestyle hubs, complete with fitness centers, cinemas, farmer’s markets, massive and unconventional attractions like indoor ski slopes and aquariums.

Rick Caruso, CEO of Caruso Affiliated, speaks at the National Retailers Federation’s annual convention in New York.

Before launching into the spectacle and staggeringly high cost of this overhaul however, it is worth noting the hesitation caused by a culture of surefire investment in commercial property that has hindered, and in some cases, already doomed particular malls and retailers.

The Rise of the American Mall

Following their inception in the 1960s, the spread of malls to suburbia grew rapidly and confidently as downtown areas fell into decline. In a review of one of America’s first enclosed malls, Architectural Record called it “more like downtown than downtown itself.” As these malls grew in popularity, so too did their bankrolling parents – the Real-Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Created by Congress in the 1960s, REITs are companies that own and often operate income-producing real estate. These large-scale proprietors enable ‘average investors’ to purchase equity in commercial projects. REITs provide investors with a pro-rata share of income while offering an easy gateway to the benefits of real estate ownership without the common obligations, risk, or expenses. REITs investors also enjoy special tax treatment – an REIT is exempt from paying federal income tax so long as it pays out 90% of its net income to common shareholders. Though REIT stock took a hit in 2008-9, with many forced to slash dividends to investors in order to free up cash flow caused by the recession’s contractions, most of these dividends rebounded in 2010-11 thanks to severely lowered interest rates. Because REITs borrow money short term to fund their purchase of long term investments, they benefit from the Federal Reserve’s ‘tapering’ or quantitative easing policy. By increasing the money supply, the Fed drives down interest rates to the benefit of REITs.

REIT stock has risen significantly, mirroring lowered interest rates.

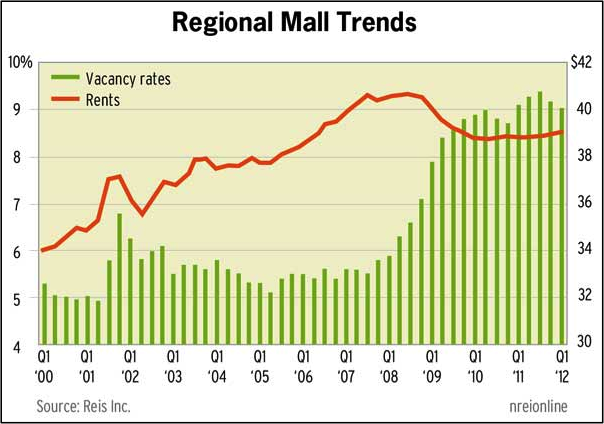

This benefit has not, however, translated into economic recovery for most malls. Following the 2008 collapse, consumer and personal spending as well as retail sales sunk to record-lows. Bottoming out in 2009, personal spending was down -1.5% from a high of 0.6% while retail sales slumped to -3.0% over the same period. Yet across the board, these losses were expected to reverse along with rising economic activity. As Jeff Jordan points out in his 2012 blog post for Quartz, however, vacancy rates and rents have “shown virtually no improvement” despite economic revival. As REITs and retailers have reshuffled their finances to accommodate for this lag, the focus has shifted to luxury goods and overseas sales. The rising demand for value or luxury items has been well-documented, in the fashion industry, between supermarkets, and even with malls. This polarisation has resulted in a widening gap that leaves many middle-market brands (and their respective malls) in a literal no-man’s land. For example, mid-market retailers like J.C. Penney and Sears, concerned with market saturation and oversupply, have begun cutting back on stores, raising mall vacancy rates across the country. In contrast to the relative stability achieved between 2002 and 2008 vacancies at regional malls spiked to 9.4% in Q3 2011, according to a Reis Report. The mid-market, as a whole, is expected to decline by 1-2% per year through to 2017, according to a recent article in Forbes.

Industry-giants like Simon Property Group have already adjusted for this market shift. The group recently isolated its ‘traditional’ properties saying that “it will spin off into a separate company its strip centers and smaller enclosed malls.” At the same time, REITs have capitalised on the rapid recovery of the nation’s affluent, seeing increased performance in Class A malls, which demand the highest rents. In comparison, Class B and C shopping centres that serve lower- to middle-income crowds remain in deep trouble. While vacancy rates for Class A malls have dropped back to and even below their pre-2008 levels, B and C malls are faring significantly worse with vacancies still 40% above pre-recession levels. The future of these malls, who occupy the mid-market position and are removed from the now-bustling and hip areas in-town, is bleak. Though some have been successfully converted into community centers, churches, and schools, their ultimate demise (and demolition) seems almost inevitable.

Middle-market stores like J.C. Penney have seen a crippling decline in foot traffic and sales-per-square foot.

Towards the Future

Despite this apparent impending doom, however, there is hope for the better-off malls and retailers to achieve success. Many malls have adjusted their offerings for the digital era, selling products less conducive to online sale, like jewellery and sporting apparel. At the same time, a more diverse selection of stores, particularly small brands, keeps things interesting.

“The industry was effectively finished, no one wanted to shop at a store anymore,” says Ton Van Dam, a Dutch businessman and shopping center tycoon. “But we have evolved, and now they come to try and compare different brands, to engage with the product.”

Ton Van Dam

A founding partner and former investor in Multi Corporation, a shopping centre developer responsible for more than 180 shopping centres across 12 European countries, Van Dam stresses the need for a complete shift in the way retailers operate.

“It is all about selling and sharing the experience” he goes on to explain. “The main focus now is experiential shopping, creating an in- and out-of-store experience and community that…motivates people to be part of it in person, to share it with their friends.”

The experiential focus Van Dam describes is already a fast-emerging trend among retailers. British fashion-house, Burberry, made waves as was one of the first to offer a digitally-integrated shopping experience. In its flagship store, full-length mirror screens in the fitting rooms correspond with radio chips in clothing to show the item being worn on the runway. Store associates recommend products based on data from iPads that log all the items a customer has previously purchased in store or online, allowing for a more personalised shopping experience.

“The aim of these efforts is to bring Burberry’s online brand environment, Burberry.com to life in a physical space for the first time” says Burberry Chief Creative Officer Christopher Bailey.

Burberry’s in-store experience merges the digital feats of its Burberry.com ecosystem with the personalisation and attention to detail in its stores.

In the US, Verizon Wireless debuted its first ‘Destination Store’ at the Mall of America. A dynamic space that allows customers to interact and engage with the products on offer, the store includes six ‘lifestyle zones,’ that give customers the opportunity to use the technology in scenarios relevant to them.

The Verizon Destination Store encourages customers to interact with products in scenarios relevant to them.

Malls have like the Mall of America have diversified their offerings by expanding into non-retail categories. The Minnesota-based mall is hoping to become more of a destination, planning to include an office tower and J.W. Marriott on site. The Dubai Mall, the world’s largest, plays host to 75 million people a year. It features a 10-million litre aquarium with over 400 sharks and rays, as well as a ski slope and an ice rink.

The Aquarium at the Dubai Mall, the world’s largest.

Harnessing the power of e-commerce as opposed to resisting it, these malls and retailers are working to transform the shopping experience. Digital and online sales offer a host of measurable metrics that allow companies to form a deeper understanding of their customer. Basic tactics include the personalisation of the shopping experience, dynamic pricing strategies, and easy-access to post-sales service.

“The digitalisation of our brand has been one of the biggest challenges faced by the company,” says John Clarke, Vice President of External Communication at the 140-year old HEINEKEN International. “But it has also given us fantastic ways through which to better understand our customer, their habits, their preferences. It has really altered the way we approach our communications.”

In addition, digital sales have greatly altered the supply chain. Customers now visit stores to compare products, only to buy them online later. Similarly, customers can request in-store pickup, allowing retailers to stock precise amounts of particular products and offer a more tailored product selection. Today, the shopping experience begins end long before customers cross the threshold of a physical store. More and more the brick and mortar environment feeds off of what is happening online, anticipating customer needs. In Apple’s retail stores, ever the shining beacons of forward-thinking retail, technology called iBeacon, which uses short-range technology to track how customers move around in-store, sends relevant promotions in the form of push-notifications.

The integration of digital into the actual product, too, has gained stead. Heineken created “the Sub,” a pressurised countertop beer tap that chills a chosen ‘torp,’ a mini-keg of torpedo-like design in order to pour the perfect beer without even leaving the kitchen. HEINEKEN International offers several of its 250 different beer brands in torp-format. Merging physical and digital, the Sub measures which torps are consumed most frequently and makes recommendations via a smartphone app to order more torps of the same or similar brand when they run low.

The Heineken ‘Sub,’ allows beer enthusiasts to swap different beer brands in the form of ‘torps.’

The number of behemoth malls that dot the American and global landscape almost certainly prevent them from going extinct, however bad business may be. But for many of these malls, which occupy the traditional space, their success depends on the ability of management and brick and mortar retailers to enhance the mall experience. The nation’s top malls leverage their sheer size to go beyond retail, moving instead to engage their customers with a relevant, changing tenant mix and exciting design, their success shows there is still viability in the mall model.

The Resurgence of Some and the Death of Many

The number of malls that dot the global retail landscape almost certainly prevent them from going extinct, however bad business may be. Success, though, hinges on the ability to adapt to the changing retail climate. For many of the malls in the traditional space, their age, location, and design mean it may well be too late. Built for a past retail heyday, the already uphill battle to transform retail combined with a massive oversupply of property, the fate of these malls is mostly decided.

For the nation’s top malls, though, the ability to leverage their sheer size to go beyond retail, moving instead to engage their customers with a relevant, changing tenant mix and exciting design, and achieve success shows there is still viability in the mall model. For now, the experiential shopper is entertained. But one must ultimately wonder, for how long?