Sam Nguyen wakes up everyday at around 8 AM to drive to work at his movie rental shop, “Video Town,” located in the city of Hawthorne. Throughout the rest of the day, he is met with a string of long-time customers that are either returning a movie or asking him for help on what the best new release is to rent.

“Is this movie good, Sam?” one 5-year-old boy asks, holding up a DVD.

“It’s horrible,” replies Sam, with a little laugh.

Sam has been fortunate enough to be able to keep his shop open for more than 15 years.

Sam, of course, is the exception.

With the sudden business transaction between Time Warner Cable and Comcast that was followed by Netflix paying Comcast for better streaming access, it is safe to assume that a majority of viewership is shifting towards the internet.

And although the majority of the attention is about the relationship between television shows and broadcasting channels, others are also discussing what this new found partnership means for the movie industry and what it has at stake from a financial standpoint.

The movie industry has not exactly been on smooth land. While almost all of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA)’s theatrical market annual reports show consistent progress, there are some cautious points to take into account.

Both the numbers at the box office as well as the ticket prices continue to have consistent progress, increasing at a good rate for more than a decade. But what is important to note here is the number of people that are actually taking the time to go to the movie theater.

There has been no consistent increase when it comes to audience. In fact, the graph above shows that the number of audience going to movie theatres appears to have reached a plateau with no signs of progress for the future.

There are a lot of signs that show lack of progress when it comes to the “physical audience” in a physical space.

Even when those movies have left the theaters and begin their way to the land of renting and purchasing movies from specific local businesses, not as many people are racing to get there at midnight.

What caused this very gradual shift?

Back in the mid 1980’s, US citizens would rush to stores in order to access their favorite movies without having to depend on television broadcast schedules telling them when they were going to watch it. In the 90’s, as Blockbuster rose up, making $785 million in profits on $2.4 billion in revenues: a profit margin of over 30 percent in 1995. However, what is important about Blockbuster’s success was all the profit it made from overdue and late fees from customers who would forget to turn it their rentals as scheduled and the fact that people had no other method of viewing movies, aside from actually buying the movie.

But things have changed.

These “brick and mortar” shops are facing large competition from technological alternatives. Instead of going to a local rental store such as the once-upon-a-time giant Blockbuster, one can now quickly go to the grocery store and pay for their bread and then quickly rent out a movie from a Redbox machine all before leaving the store. It is important to note that a majority of Redbox success comes from the profits they make from late fees they acquire from their customers, allowing it to have a promising future.

Or if that is too much of a burden on people, the existence of Netflix and Amazon provide even more convenience by allowing consumers to access whichever movie they want from the comfort of their home. Netflix started their business model by showing commercials that focused on the fact that DVDs could be mailed to one’s house and one could mail it right back in the same envelope–and with no late fees.

Amazon also provides the same alternative to consumers, allowing them to both rent and buy movies from their website. Blockbuster attempted to compete with these emerging enterprises by creating its own website, but by 2007, it was tanking and going on the verge of bankruptcy (which it declared in 2010).

Even to those that are still seeking a physical space to purchase their product, the opposite is expected. Much like the way that Redbox is offered at grocery stores or outside convenience stores, the interior of the Redbox itself provides lots of options. One has the choice of DVDs, Blu-Ray discs and even video games when searching through the “Box”.

This abundance of product is why locations like Target or Best Buy seem to be struggling a bit when it comes to DVD and Blu-Ray sales. Joanna Cantu, manager at a Best Buy in Lawndale, CA, believes that Best Buy has been able to stay afloat for the moment because of the variety of products they sell when it comes to watching movies.

“Here, one can go into the DVD or Blu-Ray section and see something they like, want to buy it, and then decide they also need a laptop to watch it,” she said.

But the way that both DVD and Blu-ray sales are shifting towards that is hurting the Best Buy stores around the country. In a recent report by Zack.com, analysts reported that Best Buy’s ESP earnings had dropped for last year and were more than likely to drop for this year as well. Even their Zacks Industry Rating was 257 out of 265 (at the bottom 3% of all the companies that it ranks).

Best Buy might still get a majority of its profit from selling laptops, tablets and smart phones, but it is the movie purchases that are still going to stop it from surviving.

So what allows small exceptions like “Video Town” to survive when even big names like Best Buy are struggling?

For one, Nguyen receives a majority of his revenue from both customers wanting to rent the newest movie that is out but also those that wish to rent movies that are not available on Netflix or at their nearest Redbox. Amazon certainly gives Video Town a competitive run for its money but Sam Nguyen has always had a consistent price in his establishment.

Customers have a choice between renting one movie (regardless if it is a DVD, Blu-Ray or VHS) for $3 or purchasing three of them for $5. He rents out video games (he even has video games for Nintendo 64 available in his store) for $2 each and has a section for movie purchases for $5 each.

The other source of profit that Nguyen makes is from late fees. Video Town charges three dollars for every day that people do not return their rentals and the store owner notes that even though the town is relatively small, people will go days without returning their rentals.

“I always wait exactly one week before I have to call customers and remind them,” Nguyen said, “and you’d be surprised how many people I actually have to call.”

Still, there is no denying that movie rental shops are now talked about once in a blue moon. There are overwhelming different forms of getting a movie once it has stopped being shown in the movie theatres.

What is even more threatening is the emergence of taking out this fine line between movie theatres, movies at home, and access to the internet. Slowly, it is becoming all intertwined into one big thing.

Televisions are now being turned into Smart TVs, where you can access your cable channels and switch onto Netflix with the click of a button.

But if that is not enough for consumers, particularly to the younger demographic, Microsoft’s newly released Xbox One now has an update coming up later in March that will allow players to watch video, play games and chat with friends all on one screen. Video includes movies which players can purchase and save in their Xbox One hard drive to watch whenever they want.

There has not been any speculation about Comcast going into the video game console industry, but considering the way that this lure into the Internet spectrum is flowing, one can only assume that Comcast is patiently waiting for the appropriate opportunity to do this.

What is important to note is that both big and small stores, and even vending machines are relying on one thing: customers going to those place consume their products; products, which is important to note, that have to be made.

The music industry has been fortunate enough to see a rise in vinyl sales, but can the same be said for the movie industry?

What happens when DVDs and Blu-Rays are no longer being made?

There is already evidence of these products being hurt by those that simply pirate movies and shows from websites. An 11-employee Independent U.S. film distributor, Wolfe Video, an independent American film distributor had its profits halved due to piracy and costs to mitigate damages from piracy in 2013, according to The Wall Street Journal.

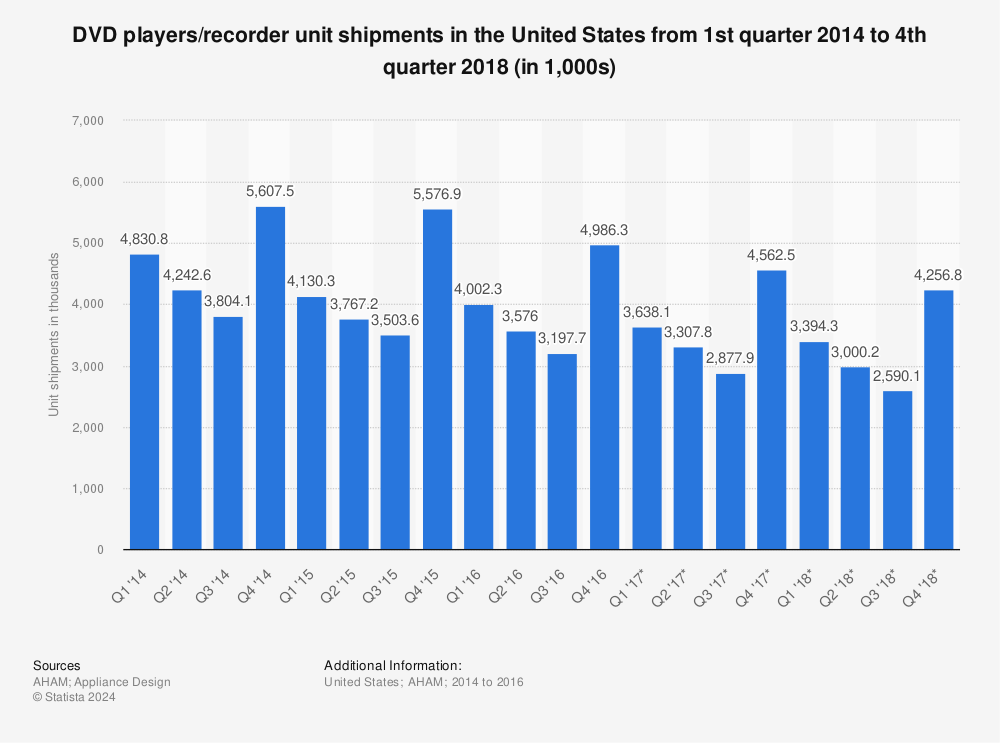

DVD sales have not been having the great track record these past couple of years and there were not many releases for Blu-Rays.

Even Netflix is showing a gradual shift away from their once marketing strategy of DVD shipments to the home.

It is all about accessibility and convenience when it comes to consuming movies or shows and having one product to do that. Everything is a bundle and DVD players or Blu Ray players being sold as sole products (not combined with anything) has not been consistent.

There is only a matter of time before the streaming becomes the only form of consumption and neither Best Buys or even exceptions like “Video Town” will be able to hold on.