There was a clear method of monetization through advertising in the early days of journalism, back in the 1900’s when news outlets ruled mass communication and information. This notion is considerably less strong today with the inclusion of user-based social media and the competition its brings that directly affects advertising revenue.

In the 1900’s, print newspapers were great at making money because people were paying for content on the physical product, and advertisers were paying for the remaining space on the physical product (two strong streams of revenue).

Now, our world is full of sleek touch screens that serve as the hardware for all sorts of information. The product has changed. Humans don’t turn pages that much anymore when it comes to consuming news; instead, consumers hope the digital format acts fast with the pressing and clicking buttons. And reliance on print newspapers for other important reasons—to find a house to buy, for example—is not needed in the age of the internet when you have .com’s with simple-to-use categorization methods.

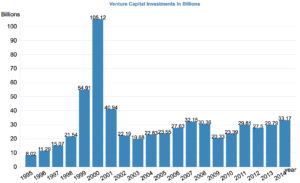

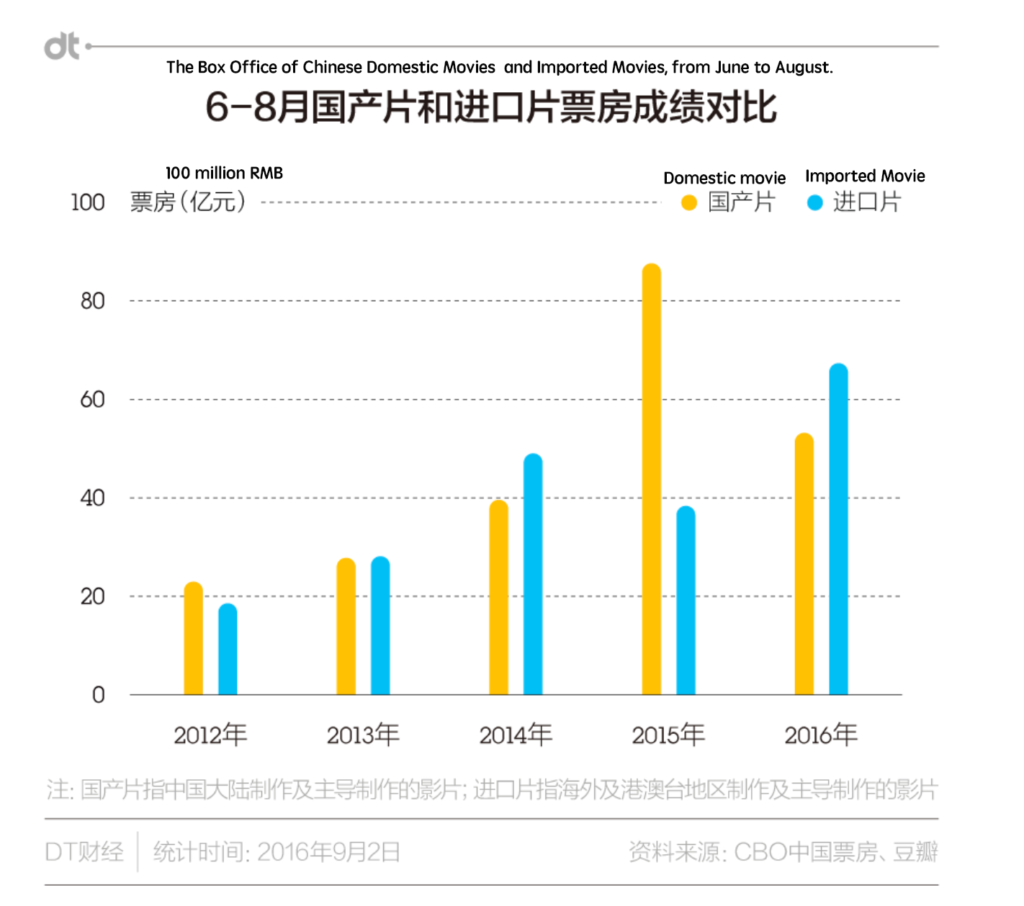

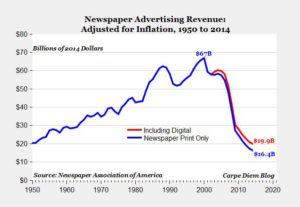

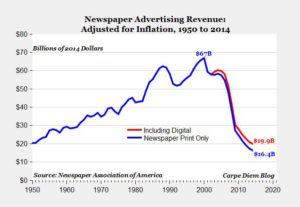

Newspaper advertising was at its peak in the 1990’s, via the graph below, bringing in $67 billion of revenue before digital advertising became legitimate after the ascension of the internet. Newspaper print advertising dropped to $16 billion in 2014, while the digital revenues of newspapers ($19.9 billion) total near the same amount.

Like a print newspaper, computer and phone screens of the digital realm have space for advertising. So, it should come as no surprise that with less people paying for a physical product, news outlets have become more reliant on advertising revenue generated from the screens of phones and computers.

But people in general don’t get excited about digital advertising. Our quick-acting phones may be a factor in supplementing this obvious distaste for digital advertising, as numbers in 2016 show that over 80 million Americans were projected to use ad blockers that year, which cost digital media companies about $10 billion in revenue, according to EMarketer.

As difficult as it might be to utilize advertising revenue on a computer screen, it’s even more difficult to advertise on mobile phones because they’re smaller devices that make it easy for ads to take up the entire screen and seem pretty obnoxious.

Since news organizations’ advertising is driven by the amount of room available within the confines of a page, there is a limited ability to advertise, and advertising revenue can only generate so much monetary gain for news outlets.

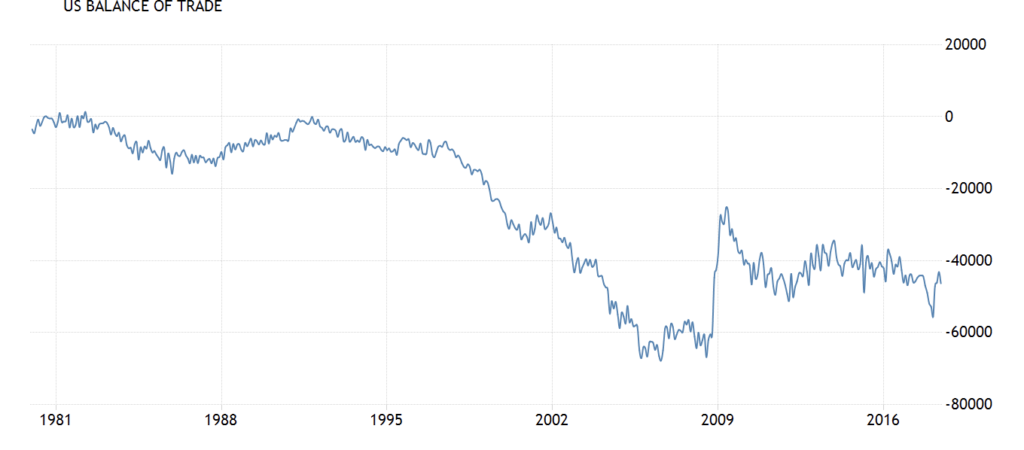

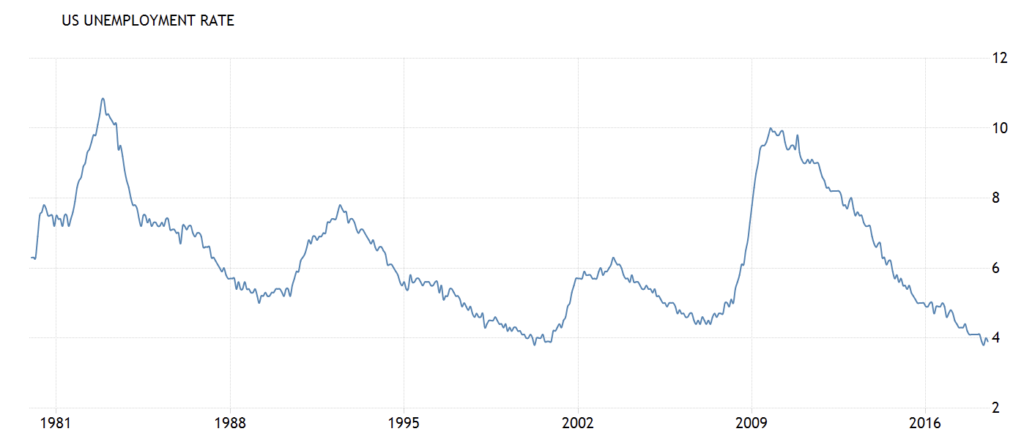

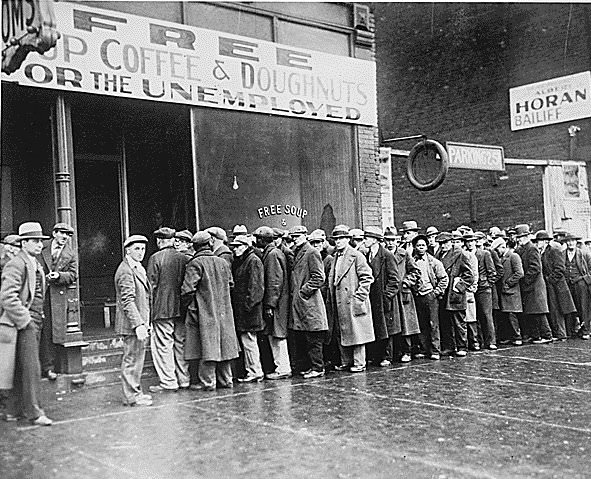

After all, advertising is a business of ebbs and flows; if the economy is flourishing, revenues will most likely be higher. So when 2008-2009 hit, people thought that newspaper advertising revenues would see significant recovery when the economic downturn was over. That hasn’t happened, especially through digital means.

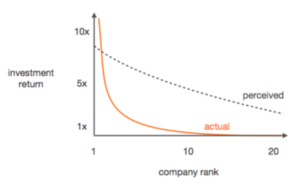

“While that digital ad pie is growing, the numbers show that news organizations are competing for an increasingly smaller share of those dollars,” wrote Kenneth Olmstead for the Pew Research Center.

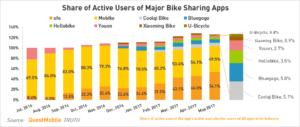

A notable issue exists within the new digital framework we live in, contributing to news organizations’ “increasingly smaller share” of those digital advertising dollars. News outlets aren’t frequented to the same level as they once were, since more competition comes from blogs and social media, like Facebook and Twitter, which are driven by new media consumption habits.

Instantaneity and an abundance of content are indicative of what social media is, compared to traditional news media which usually needs some sort of verification from an editor that doesn’t make it instantaneous. And newspapers’ content is often professionally produced, so its output isn’t as plentiful as what’s generated from free-flowing social media.

The reality of this digital age can be summed up simply. As social tech giants continue to rise and have a wide base of consumers online, it’s clear the more engagement you have, the more potential exists for advertising.

“Ultimately advertising is about selling attention, and if most of that attention is focused on Google and Facebook, then naturally they can monetize it,” Balderton Capital venture partner Suranga Chandratillake told the FT.

According to The Guardian writer Roy Greenslade, Facebook’s net income increased 300% and its margins jumped from 26% to 37% in the first quarter of 2016.

“In effect, 90% of the increase in mobile revenue is going to Facebook and Google,” Greenslade wrote. “Combine this with agencies’ own income influencing advertising decisions, and the internet begins to resemble a monopoly based around algorithms rather than a supposedly neutral distribution platform.”

Facebook can move the right ads to the right audiences and better exhibits user engagement for ad agencies because the company holds about 98 data points per user. This function basically allows advertisers to target specific people with specific interests, leading to more effective ad placement. News organizations have failed to capitalize on social media’s new-age comprehension of behavioral economics.

The average media consumer’s focus shifting from news organizations to social media is also because destinations like Facebook feel so unique.

Social media is user-based, meaning anyone with access to the internet can build virtual communities and contribute to worldwide communication, and those who were once voiceless can have their perspective seen for its good and bad consequences. It’s an idea that feels like democracy, bringing power to the people in a sense, but also feels too open for slander at times. We can very simply broadcast ourselves to mass audiences, and the initial and constant gratification gained from this wide-spanning personal connection is present in millions of people.

Therefore, trying to compete with media companies that have such power over mass communication is, and will be, tough for news organizations. Facebook, for example, has media organizations working with them in such a way that Mark Zuckerberg’s company seems to be the one in control.

“When Facebook says it will prioritize video in News Feed, every publisher that can afford to do so builds a video team….Facebook is setting the rules, and news organizations are following,” WIRED staff writer Julia Greenburg wrote. “That’s concerning because the news industry is in a precarious way. Publishers have finite resources and limited time. Staff are overworked and underpaid.”

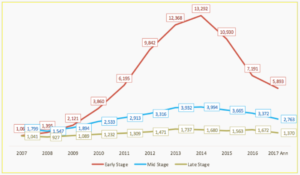

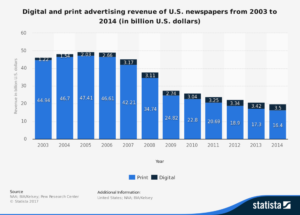

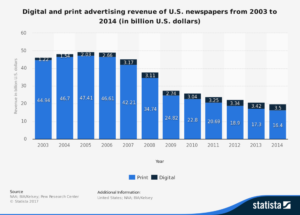

Online ads for news outlets have increasing revenue each year, so that’s not a problem. From 2009 to 2014, U.S. newspapers went from $2.74 billion in digital ad revenue to $3.5 billion, according to the graph below. A $1 billion increase in five years wouldn’t look bad if digital ads had been used by newspapers since the mid-1900’s. But that’s not the case, as the main source of advertising originated on the print newspaper, and in 2003, print ad revenue was $44.94 billion. In 2014, that number dwindled to $16.4 billion.

“Online advertising is looking more and more like a contest that publishers can’t win—not on a large scale, at least,” Slate’s Will Oremus wrote. “Advertising can help to cover some of their costs, but online ads alone won’t pay for big, serious, high-quality journalistic enterprises the way that print ads once did.”

In the early 2000’s, news organizations were optimistic by thinking that their revenue streams would work out. They weren’t able to forecast that fewer people direct their attention to digital ads, making them less reliable than print ads. By not having every news organization construct online paywalls 15 years ago, consumers now expect online news is there for reading, not ad viewing, while there are so many other entities on the fast-paced internet that can redirect one’s attention — a combination of realities that puts news sites in a conundrum.

Even though a lot of newspapers thought digital ad revenue was going to pay their bills so that they wouldn’t need an online paywall, there were some that went in a different direction, such as the Arkansas Democrat & Gazette. This paper allowed free access to the website, but only if the reader had subscribed to the newspaper.

“For the last 10 years we’ve remained steady in both daily and Sunday circulation, whereas other markets have seen 10-30 percent drops,” Conan Gallaty, director of the paper’s website, said.

The New York Times has adopted this method as well. But if many outlets were to do this, the value of print newspaper advertising could plummet because people are still going on their computer and viewing the news online, while the actual paper sits in front of their house collecting dust. The decline of print newspaper advertising would accelerate at an even faster rate, and many would argue there’s no point in trying to save it.

Another subscription-friendly site is the online publishing platform Medium, which thinks its future of revenue is rooted in subscriptions that are free of ads, costing around $5 a month and featuring exclusive content. Stratechery, run by one man, Ben Thompson, caters to lovers of tech and media and is $10 per month for a subscription. Similar to Medium, exclusive content exists by paying the monthly fee.

“Making advertising a secondary — though still vital — revenue source is the most important strategic goal for most news publishers,” Ken Doctor of Newsonomics said. “Reader revenue, if backed by sufficient high-quality content and good digital products, proves far more stable than advertising.”

The subscription fees might get people who don’t read a paper to still monetarily contribute for the news. After all, since the older demographic reads physical newspapers, there continues to be less and less print readers as they die off.

If subscription fees can’t get the job done for some of the medium-to-large media companies, then what’s the next step for their revenue? One method could be having a team of journalists do consulting and market analysis for clients that are willing to pay, considering the writing and analytical skills of experienced reporters covering certain beats are considered to be of high-quality.

New organizations could also step up their push for revenue by selling merchandise, striving for unique consumers goods like entertaining clothing. But there’s a strong belief that news organizations have to do a better job enticing people into their online community. Video is being used more often in producing news, but the interactions between the readers is still fairly basic with the use of a straightforward comments section. Building other initiatives into the experience of watching video and reading text may really help these news organizations.

There’s also a possibility that someone alters the composition and experience of the ads, and not the news content. It’s unknown how this would actually look, but attaching social meaning to the ads through reader voting and reactions could be along the right line of thinking.

Clearly, retaining reader engagement poses a challenge for news companies. And their current situation can only get worse — unless a group of forward thinkers hits the nail on the head with one or many solutions.