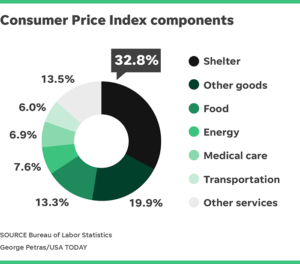

In the world of economics, real numbers, unsurprisingly, have always been the pinnacle of people’s attention. Economy is about money, and what better way to talk about money than numbers representing actual money involved in the economy. However, there is always more to the big picture than meets the eye, and besides the buzz around more commonly used economic indicators, such as Consumer Price Index, and Producer Price Index, the less talked-about, and lesser-known Consumer Confidence deserves much more recognition than it currently gets. Consumer Confidence is, in fact, monumental, in that it reflects on many of the most important areas of the economy, such as housing, unemployment, and inflation. Furthermore, unlike CPI and PPI, trailing indicators that document the past, Consumer Confidence, a leading indicator, often times paints us an accurate picture of what the economy looks like in the foreseeable future, and that is where the key difference lies. Although there is much to be learnt from the history and the recent past, we study economics for the future, and more time and energy ought to be devoted to analyzing stats that predict economy in the future, rather than the past.

Consumer Confidence is, in itself, a comprehensive, yet somewhat abstract indicator due to the many factors that come into play when it is calculated. When being asked to consider future expenditure, consumers would weigh their economic circumstances carefully, and give their opinions, namely, confidence level. The higher the Consumer Confidence in general, the more consumer-friendly the current market and economy is, and the more consumption will be taking place. Because it is measured by opinion polls and surveys filled out by the general public, the results are directly from the consumers themselves, and so is highly representative of the overall consumption in the next six months. It is relatively abstract because the Consumer Confidence numbers will be a result of many aforementioned factors combined, without clearly stating how each is faring in specific. Still, it does its job in predicting the general trend of consumption in an economy.

While indicators like CPI and PPI presents a picture faithful to economy in the past, Consumer Confidence takes advantage of conditions of the near past and present to make an outline for the future. Granted, we could look at the pattern of recent CPI and PPI, and predict that it is highly probable that the trend will continue. But, these indicators being what they are, in essence, trailing indicators, they have no way of estimating a change in the pattern ahead of time. In economics, timing is crucial, and a leading indicator like Consumer Confidence has the benefit of providing people with the convenience of being able to know what happens ahead of time. The leeway helps governments to be Johnny on the spot when making new policies, and can prevent them from losing money. More analysis on Consumer Confidence can prove quite valuable for governments in the long run, for it will help stabilize the economy, and kill off potential financial setbacks before they take form.