$16.5 million — that’s how much Daniel Middleton, the highest paid YouTuber of 2017, made last year, according to Forbes. Since its founding in 2012, Middleton’s channel “DanTDM” has amassed over 20 million subscribers, 13 billion total video views and an active audience that keeps coming back for more gameplay videos.

Middleton’s position isn’t an idiosyncrasy. Falling only a few places behind him are the household names Logan Paul (18.5+ million subscribers) and Jake Paul (17+ million subscribers), who made $12.5 million and $11.5 million in 2017, respectfully. That same year, the highest paid female YouTuber was Lilly Singh “||Superwoman||” (14+ million subscribers), who made $10.5 million.

“Influencers are social media ‘stars’ who have monetised their subscriber base on Instagram by posting pictures and endorsing brands,” defines Yasmin Jones Henry of the Financial Times. The modern world of internet influencers/content creators, however, has only sprung up in the past decade, so how did these individuals go from making videos in their bedrooms to raking in millions of dollars? The answer is simple: advertisements.

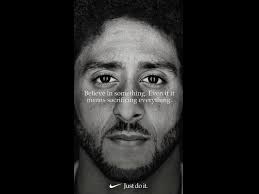

In the past, advertisers have paired with traditional media, like television and radio, to focus on larger interests in hopes of having their product be a contender for the general audiences. Influencer marketing, however, has come along with more niche, new-form media, which has allowed advertisers to hyper-target consumers for more successful sales.

“One result of social media has been the democratization of influence and creativity. We no longer need the approval of large corporations to determine what content is truly worthy of views,” writes Matthew Biggins in an article on influencer economics for Medium. Biggins is right — we, the viewers, have taken the power out of the hands of big corporations and have redirected that decision-making authority to ourselves. We decide what we like and what content to ingest, which produces a positive feedback loop of receiving content that repeatedly satisfies us. This is where influencers come in. As viewers constantly returned to the same creators for reliable quality content, the influencer economy continued to expand, leader influencers naturally to become the next tool for advertisers to use.

“Sixty percent of Gen Z are more likely to believe what a YouTube star says over what a movie star says,” said Deborah Weinswig, the Managing Director of Fung Global Retail & Technology,

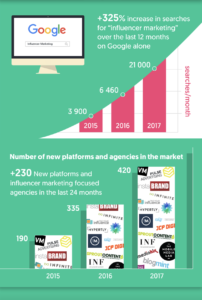

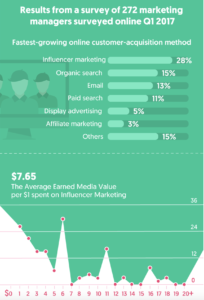

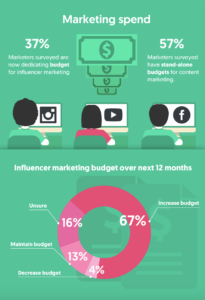

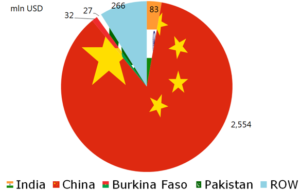

Images from Visual Capitalist.

In late 2017, roughly 70 percent of brands were using influencers. On just Instagram, which is a platform often used to establish or expand a creator’s social media presence, influencer marketing is a $1 billion industry, according to Retail Dive. Overall, companies primarily have been redirecting their advertising funds to online video and sponsoring Instagram posts, which can cost companies tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars per post.

Though influencer marketing is clearly the future of business and retail (and the large sums of money involved seem to indicate success), the newness of influencers still has kinks to be worked out when compared to traditional media advertising. While the number of traditional media viewers tends to be concretely-based, many pages with thousands of followers may consist of purchased, fraudulent fans, leaving companies to make investments they can’t be sure will yield the results advertised.

Nonetheless, the way consumers discover and purchase goods in our larger economy is changing for good. No longer can the intertwined economics of entertainment and retail sales rely on relating to the general public in hopes that something will stick.

“Beyond creating content for brands, another driving force of the influencer economy is the consumer’s hunger for representation,” writes Bof Team for Business of Fashion.

So, yes, individually liking something on Instagram is an economic transaction after all. Welcome to the influencer economy.