It is almost truism to say that when you’re young, you are, as rapper Whiz Khalifa once noted, “wild and free.” Youthful exuberance, in popular Western imagination, is epitomized by reckless. But youth, as advertised, isn’t always just about the freedom to be irresponsible. It is also true that when you’re young, you’re most free to explore and inquire in ways that you can’t really do so when you have, say, a mortgage to pay off and kids to feed. Thus, your 20s are potentially your most experimental years. That is, if you are not burdened by debt.

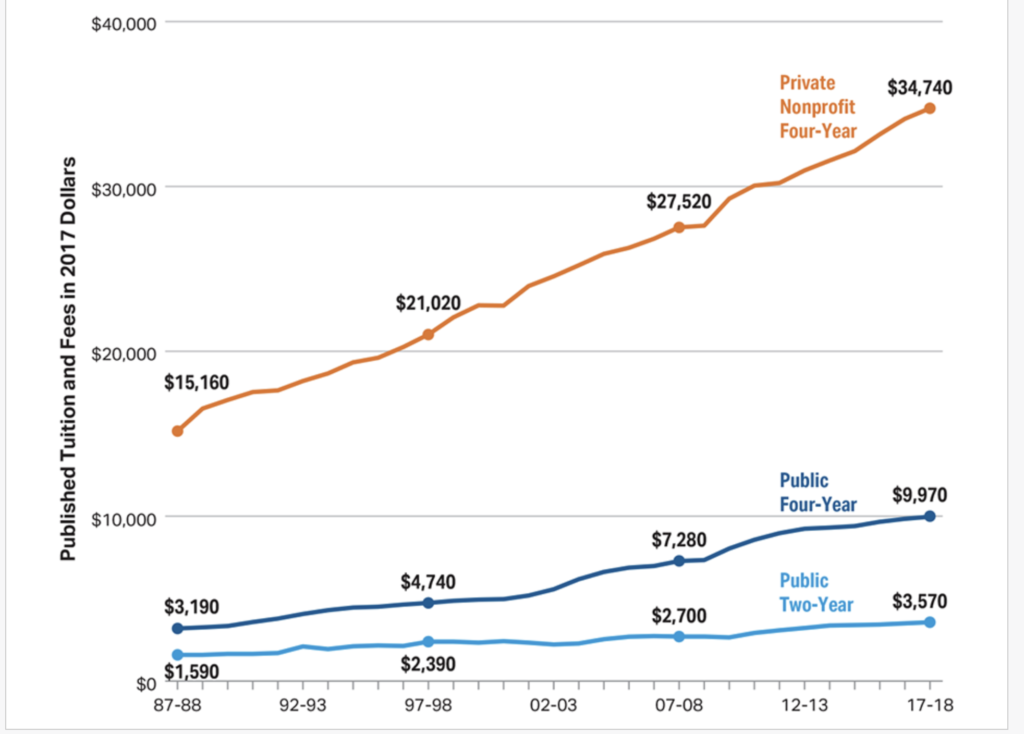

Today, students at a four-year public institution pay 213% more for tuition than they would have thirty years ago. For private schools, students pay 130% more Roughly 70 percent of graduates leave college with student debt. Total student loan debt is now at about $1.5 trillion (two-thirds of which are held by woman.).

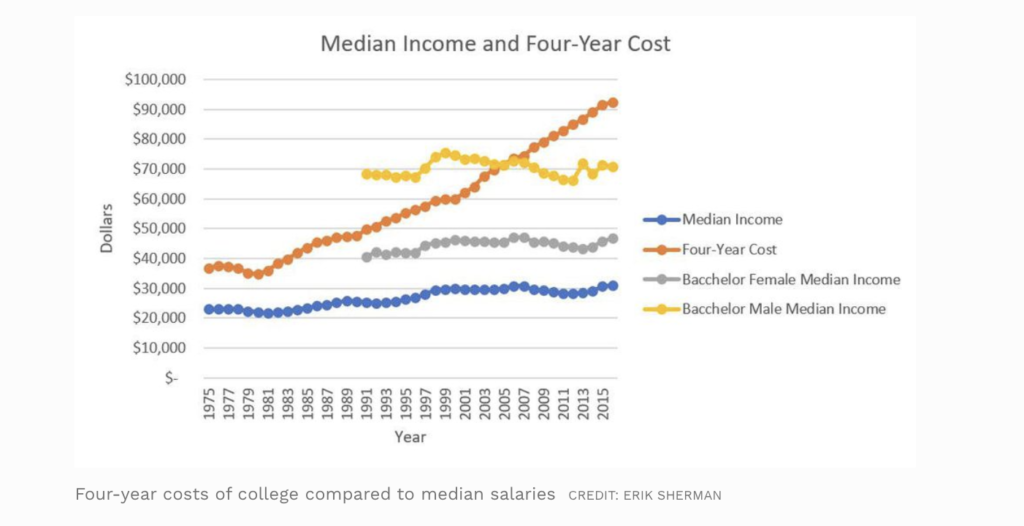

According to data from the Census Bureau compiled and aggregated by Forbes, annual cost of college, which includes room and board, tuition, and fees, has greatly outpaced median income. Even incomes for males with bachelor degrees are starting to feel the burn.

In a new survey by the Kogog School of Business, about 60 percent of millenials earning less than $50,000 a year are living “paycheck to paycheck”. Even more astonishing, about 60 percent of those earning between $50,000 to $99,000 say it’s still hard to make ends meat.

In another study, conducted by the NBC News/GenForward survey, about 62% of millenials owe more in debt than what they have saved up, with about 30% of millenials having less than $1000 dollars in their savings account and about 24% having no savings at all. Credit card debt and student loans make up the majority of the debt.

And before one jumps prematurely to the “millenials are just lazy, have bad work ethics, buy too much avocado toast etc.” argument, keep in mind, millenials tend to be workaholics, using less of their vacation time than previous age groups.

None of this is to say that these are problems unique to the young. Americans across all age groups face mounting debt. But the fact that the largest generation since the boomers must simultaneously balance debt payments while entering into an increasingly precarious labor market with few options for cheap affordable housing is cause for alarm. This isn’t just a spiritual and cultural travesty but an economic one too.

For example, in a study by the Health Science Journal on “economic growth and the harmful effects of student loan debt on biomedical research”, empirical evidence is found that supports the hypothesis that “indebtedness among young medical graduates affects speciality career choices. This means that, in the future, ceteris paribus, prospective students in biomedical sciences will be strongly incentivised, firstly, to choose the more remunerative career of medical practitioner instead of that of medical (pure or applied) researcher, and secondly to further sub-specialize in those fields that promise higher earnings to offset their higher loan repayments.”

I think this finding could be applied across most creative, professional, and specialized fields. To take just one example, there is a huge shortage (as well as underfunding) of public defenders. It’s highly possible that many attending law schools, even those with deep interests in public defense, go instead into corporate law for reasons similar to those cited in the above study: that is, to offset loan repayments or reduce precariousness in living standards—which is becoming more precarious as wealth inequality continues to widen. What are the consequences of this? A large reserve of lawyers in defense of the most privileged and a shortage of lawyers for the most marginalized, thus furthering racial and class disparity.

So what can be done? A study by the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College proposed a radical idea back in February: cancel the nation’s $1.4 trillion student debt.

The researchers looked at what would happen if the government cancelled all federal loans as a one-time policy. According to their models, this would lead to an $86 billion to $108 billion boost in GDP over the next ten years as well as reduce unemployment by .3%. What about deficit and inflation? The report indicates only “modest” effects.

Although there are many legitimate concerns to this seemingly simple solution, it may be something worth considering—a radical solution for a radical problem.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.