In 2015 it was Greece. In 2018 it has been Argentina, Venezuela, and Turkey just to name a few. Across the globe, those countries unable to execute the delicate ballet of monetary policy have seen staggering inflation, interest rates to match, and devalued currency. Perhaps most urgent, however, is the inability for these countries to pay back loans. Even more, 40% of low-income developing countries (not always sprawled across headlines) are either in a debt crisis or nearly there.

Let’s look at Turkey, for example. Despite raised interest rates (now at 24%), inflation is at 18% and the country doesn’t appear solvent enough to repay the foreign money dumped into the economy over the past few years. GDP is expected to contract in Q3. Just yesterday, Turkey’s Treasury borrowed around $347 million at the interest rate of 25.05%. These numbers scream impending doom. As interest payments come due, Turkey will likely have to refinance the loans or, more probably, borrow more money, this time at an even higher interest rate. This process will increase the deficit again, drive interest rates higher, and propel the positive feedback loop yet again.

It’s easy to sit behind the news headlines, shaking our heads at the recklessness of Treasury officials in Washington or Ankara or Buenos Aires or Athens. The reality is, however, that this insidious cycle happens not merely within governments, but also within a much quieter space—the world’s poorest.

A financial epiphany hit the world in the 1970s: microfinance. As inflation was skyrocketing in the US, nonprofits began to understand and prove that the “poor are creditworthy.” This realization opened the door to a now widely used process that allows individuals who wouldn’t ordinarily have access to capital, such as women in sub-Saharan Africa, to be granted loans to start small businesses. This reinvention of the financial system promised the potential to become a powerful tool in alleviating worldwide poverty.

But people, like governments, have trouble with debt.

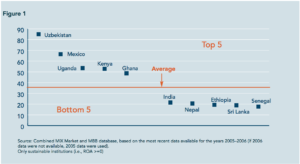

Source: CGAP

While the lending interest rate in the United States was about 8% in 2006, the average microfinance interest rate was about 35%, as shown in the figure above. For individuals in Uzbekistan, that number was 85%. It’s intuitive, practical, and even necessary for lenders to be compensated for risky investments through higher interest rates; this reality, however, leaves individuals trying to start a small business, like Greece in 2015, broke, desperate, and unable to attempt repayment. For microloan recipients in India, the reality was bleaker than desperation. “More than 80 people [took] their own lives in the last few months after defaulting on micro-loans,” reported the BBC in December 2010. These are devastating realities for individuals who fall prey to interest rates that are wildly unsustainable.

Let’s suppose that a microfinance organization has agreed to lend $100 to a woman in Malawi to make and sell resilient water jugs in her community. Completely ignoring start-up costs, she will have to expect returns of 37% ($137) in the first year just to pay off the loan and make a 2% ($2) profit. When this woman cannot pay off her loan at the end of the year, she’s forced to borrow more money at a higher interest rate in order to pay off the first loan. Of course, it’s unlikely that she’ll be able to pay off the second loan either. This is an infeasible system.

When interest rates are highest among individuals with the least amount of power to pay them back, these citizens turn into a personification of Greece or Argentina or Venezuela, desperately looking around, pleading for someone to help pay their debts. There is no IMF for individuals.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.