Learning economics is a difficult undertaking for students like myself. Unlike biology or mathematics, economics is not tangible or easy to visualize. Even its definition–the study of scarcity–leaves me puzzled about the nature of economics as a field of study.

However, Uber, a global ridehailing service, is an economics student’s saving grace. Uber’s market is an ideal for what we want the economy to look like. It has characteristics of a competitive market: low barriers for entry, many buyers and sellers, and somewhat homogenous services. Most importantly, the prices riders pay are a direct response to supply and demand. Uber is an excellent example with which to apply numerous economic terms and theories.

Take, for example, consumer surplus. According to Britannica, consumer surplus is “the difference between the price a consumer pays for an item, and the price he would be willing to pay rather than do without it.” It’s a number that has been impossible to estimate in the real world (unless you are a fan of the Infinite Universe theory) until now. Steven Levitt, an economist at the University of Chicago, was able to estimate a consumer surplus measurement using Uber’s data, which collects information about completed trips and those that were considered (user opened the app) but never taken.

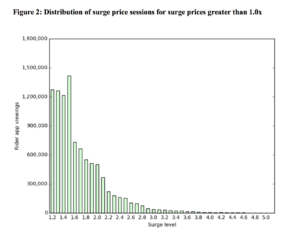

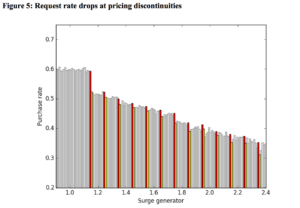

On Freakonomics’ podcast from September 7, 2016, Levitt explains that even though Uber has an algorithm to come up with the ideal prices of surged rides, the company instead only multiplies the cost by tenths (1.1, 1.2, 1.3) for customer convenience. This series of minute discontinuities allows for the estimation of the price-sensitivity of Uber riders.

Now, what is price sensitivity? In Greg Ip’s The Undercover Economist, he explains the concept: “when I raise the price, how much do my sales fall? And when I cut the price, how much do my sales rise?” So, it’s the extent to which the price of something affects if a person will buy it.

Levitt examined Uber’s database of many similar consumers facing incrementally different prices to examine the price sensitivity of the riders (at what price will they leave the app instead of booking a ride). Levitt also used this data to estimate Uber’s consumer surplus. He extrapolated that in 2015 the consumer surplus in the United States was $7 billion, which means that riders were willing to spend $11 billion on rides, but in reality only paid $4 billion.

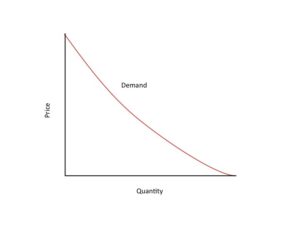

The “Regression Discontinuity Analysis” that Levitt used to estimate consumer surplus can also be used to illustrate a real-life example of the demand curve. Britannica explains that the Demand Curve is a graph illustrating the relationship between price and quantity. The curve slopes downward from left to right because price and quantity are inversely related. It’s an artificial construct that economists use to examine real-world situations. But once again, Uber can be of assistance. Uber’s price surging data, all of the small jumps in price faced by similar consumers, can be added together to discover an instantaneous demand curve. When there is no surge, the price of rides is average and so is the amount of drivers. As an oversimplification it can be noted that demand is at equilibrium. When surges occur, prices go up and and the amount of drivers available declines, so demand is high.

Uber has been in the news a hundred times over for all of its scandals and controversies. But Uber deserves more positive press–it led me to pass my econ quiz!