Hurricanes, earthquakes, and wildfires … America and the world have been entangled by natural disasters recently. The natural disasters never could be considered as a positive force because of the destruction and death the bring. However, disasters also tend to make reconstruction the primary task for the government, making it easier for public money to flow into hard-hit regions. Economically, in what case would natural disasters be a boost to the regional economics? It depends the previous economic status of the affected region and the immediate assistance efficiency from the government.

In Sichuan, China, where a magnitude 8 earthquake took place in 2008, is an example how the local economy can recover and even expand during the post-disaster reconstruction. Poor infrastructure exacerbated the damage, leading to an official death toll of 87,150 and 4.8 million people homeless, according to the BBC News. The economic loss was estimated at $191 billion, the second highest in absolute number in history, according to 2013 CATDAT Damaging Earthquake Database. The noteworthy part was that the central counties in 2008 Sichuan earthquake, WenChuan and Ya’an, were neither a raw material production base nor manufacturing zone. Actually, these counties were poor. Thus, the earthquake did not hurt the Chinese exports or GDP to any great degree.

The rebuilding efforts cost the Chinese government almost $150 billion, equivalent to a fifth of its entire tax revenues for a single year, according to the state media of China in 2008. Quickly after the earthquake happened, the National Development and Reform Commission of China announced a reconstruction plan that “envisages buildings 169 hospitals and 4,432 primary and middle schools to replace collapsed structures. Another 2,600 schools that remained standing will be strengthened. More than 3 million homeless rural families will get new houses and 860,000 apartments in the city will be built.”

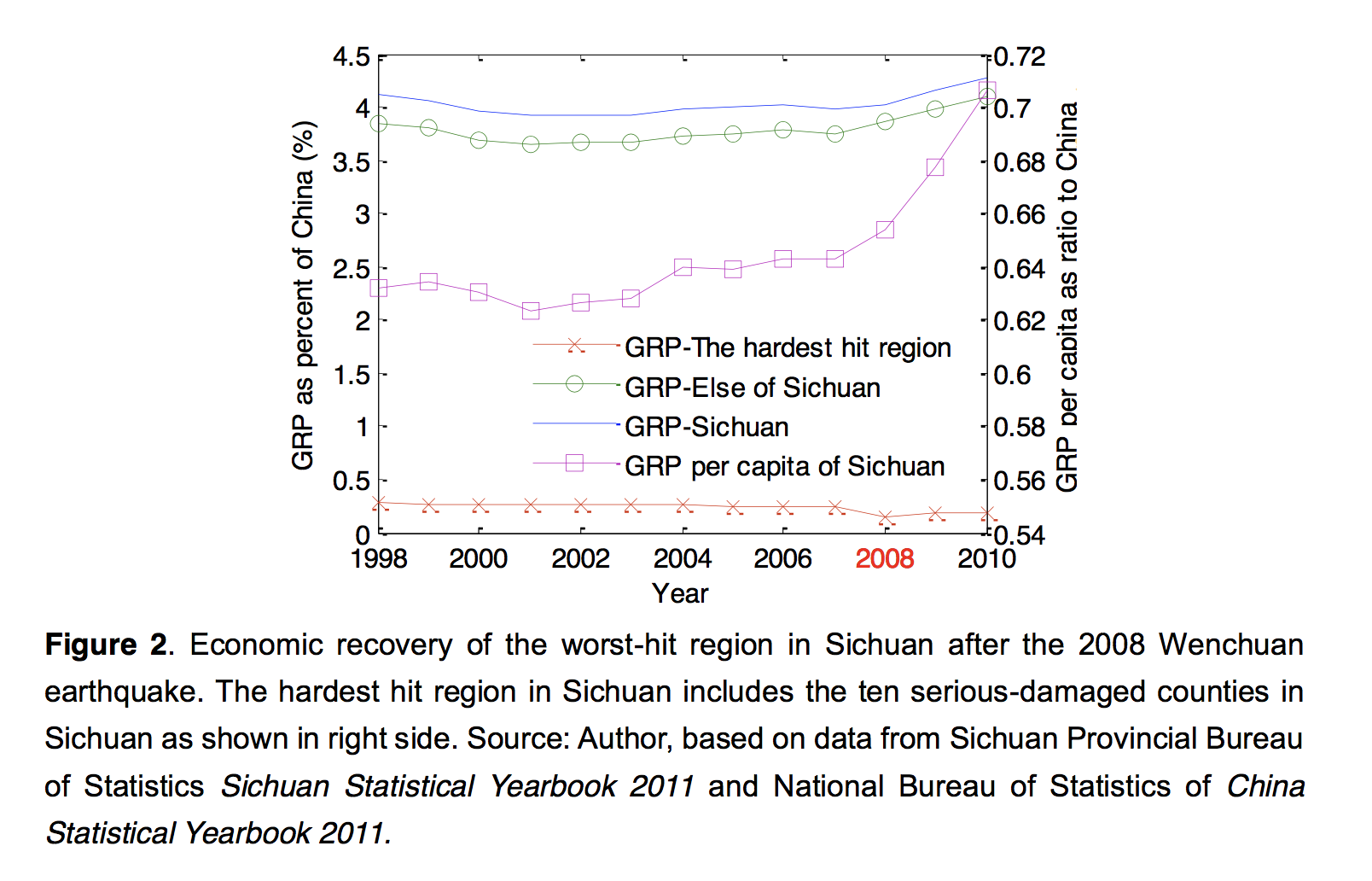

Relying on such tremendous capital investment, the regional economy of Sichuan was able to recover in an amazing speed. Here is the chart associated with the Gross Regional Product(GRP) of Sichuan from 1998 to 2010.The blue, yellow, and green line respectively indicate the GRP of Sichuan, of the hardest hit region of Sichuan in 2008 earthquake, of else of Sichuan, in the form of percent of Chinese GDP. The pinkish line represents the GRP per capital as ratio to Chinese GDP.

The graph tells that before the earthquake happened, the hardest hit region in Sichuan earthquake, which is composed of the ten serious-damaged counties, generated about 0.25% of Chinese GDP. Meanwhile, the Sichuan generated about 4.1% of Chinese total GDP.

By 2010, 2 years after the earthquake, the GRP of Sichuan and the GRP of non-central damage area of Sichuan both not only recovered but even had growth.

“The GRP level of the worst-hit area of Sichuan decreased by 35.4% in 2008 compared to the 2007 level. After three years of reconstruction, the region had still not returned to its pre-earthquake GRP level, but the GRP level of the rest of Sichuan experienced a boom in those three years because of the reconstruction demand stimulus,” according to a studies conducted by MOE Key Laboratory of Environmental Change and Natural Disaster of the Beijing Normal University.

The GRP per capital in Sichuan had a huge growth; however, it is meaningless considering the tragic death tolls.

In a article published by China Daily , by 2012 when reconstruction basically completed, the Deputy-Governor of Sichuan Gan Lin said, Sichuan was the fastest growing of the major economic provinces in China. China Daily asserts “the quake zone has seen unprecedented changes.” Governor Gan said, during the past four years, Sichuan’s GDP doubled more than 2 trillion yuan ($317 billion), enabling its per capita GDP to surpass $4,000.

*A noteworthy point for the above statement is the “go west” strategy to increase inland development formulated by the State Council in 2000 also plays an significant factor to Sichuan’s growth.

“When something is destroyed you don’t necessarily rebuild the same thing that you had,” said Mark Skidmore, an economics professor at Michigan State University. “You might use updated technology, you might do things more efficiently.” With massive amount of national resources, “the disasters allow new and more efficient infrastructure to be built, forcing the transition to a sleeker, more productive economy in the long term, a New York Times article commented on the Sichuan Earthquake in July, 2008.

More practical and explicit reflection of the benefits from 2008 earthquake to Sichuan region comes from the 7.0 magnitude Sichuan earthquake in Ya’an. According to the BBC report, “none of the buildings built since the Sichuan earthquakes collapsed.” The quality of housing for sure has improved.

However, the previous economic condition of the hardest hit region in Sichuan earthquake facilitated the recovery session. A New York Times article wrote about one month after the earthquake, “only 1 percent of China’s population lives in the hardest hit quake-affected area, in northern Sichuan Province. Those residents account for an even smaller share of China’s economic output, because many of them are impoverished farmers.” In other words, these areas might not receive this much of national investment or resources within short period of time.

The economic affects brought by Northridge earthquake in 1994 was a different story. That 6.7 magnitude quake struck an area of 2,192 square miles in the San Fernando Valley, causing 57 people killed and 11,800 injuries. It is still ranked by CNN Money as the most expensive earthquake in American history, costing $44 billion.

In the research “The Northridge Earthquake, USA and its Economic and Social Impacts” conducted by Professor William J Petak from University of Southern California and Research Fellow Shirin Elahi from University of Surrey explains the difficulty of reconstruction for Northridge area, “Northridge earthquake was a direct hit on an urban area and the scale of losses caused by the earthquake far exceeded expectations.”

Unlike regions in Sichuan, US has a large concentration of localised industries, such as the entertainment and aerospace industries in southern California, which was severely undermined by the earthquake, the research argues. Moreover, unlike most people lived in Sichuan’s affected regions were rural farmers, San Fernando Valley supports half of the city of Los Angeles’ population. “Approximately 48% of the population were homeowners – middle class and therefore not obviously insecure- yet many proved to be vulnerable to the hazard,” the Northridge Earthquake research claims.

Another important factor that determines the success of reconstruction after catastrophe is how effective and efficient the state or the federal government respond to the recovery assistance. The highly-centralized government system allowed the Chinese government to respond Sichuan Earthquake immediately, ordering national assistance and resources investment. Kevin L. Kliesen, Economist from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis wrote in his article “The Economics of Natural Disaster,” explains the difference in American government, “although emergency funds for food and shelter are usually disbursed immediately by Presidential directive, monies for longer-term rebuilding efforts are often appropriated by Congress with a substantial lag.” The research “The Northridge Earthquake, USA and its Economic and Social Impacts” criticizes the reaction from the government during the Northridge Earthquake. The research attacks the lack of “a desire for a recovery to reproduce a return to normalcy, and achieve the status quo of the socio-economic and built environment prior to the earthquake.” Many federal, state and local officials were not willing to sacrifice their own political, economic, social or environmental agenda to cooperate to help the affected regions, the research asserts. They were at best willing to make adjustment.

An extreme case is the Haiti’s response to earthquake. The Bernard L. Schwartz Chair in Economic Policy Development Martin Neil Baily wrote in an article for Brookings that Haiti, which is too poor to manage the immediate recover after hurricane, has to wait international aid to get basic rebuilding, leaving alone economic growth. It is so difficult for Haiti to recover.

The study of economy in disasters is not new. In 1969, Douglas Dacy and Howard Kunreuther, two young analysts at the Institute for Defense Analyses, published a book called “The Economics of Natural Disasters.” It was probably one of the first attempts to measure the economic influence of catastrophe. The book argues that the dreadful Alaska earthquake of 1964 helped the Alaska economy by garnering government loans and grants for rebuilding.

The theory of economic boom from disasters also received criticism.“Over any reasonably relevant period of time, society is not made wealthier by destroying resources,” Donald Boudreaux, an economics professor at George Mason University, said. If it were, “Beirut should be one of the wealthiest places in the world.” Economist Frédéric Bastiat labeled the disastrous economy theory as “the broken window fallacy” in his article “What is Seen and What is not Seen.” Bastiat compares the disaster reconstruction to fix a broken window. It costs $100 dollar to fix a window. The repairman and window shops got money because the window owner pays it. In the reconstruction case, the money comes from tax payers or just money printers. The natural disaster could be an economic boost to a region, but it always is an economic downturn for the whole nation.

In conclusion, the theory model of disastrous benefits for economy should be viewed as that the areas that would not receive national resources or investment during the normal time becomes privileged after suffering catastrophe. It also gives these areas more opportunity and capital to develop during the reconstruction period. The previous economic condition of the affected region and the efficiency of government assistance determine the success of the recovery. Despite to the regional growth, we should never be positive toward disasters because it never generates economy but merely redirects capital and resources to recover a definite loss of wealth.