Behind the Vote

Brexit. A term that filled newsrooms, Facebook feeds, and local pubs all summer long.

It’s the word that became a reality on June 23rd, 2016, when the UK voted to revoke its membership from the European Union with a 52% majority vote. The decision sent shockwaves around the world, as countries questioned what the future of Europe would look like. With such a slim victory margin from the “Leave” campaign, the decision was highly controversial and has continued to cause political, social, and economic anxiety in the months since.

The official campaign for Britain was called Vote Leave, and was built on the notion that the UK had to leave the EU in order to protect its borders, strengthen its economy, and increase employment and wages for British nationals. Immigration was one of the most important components of the Vote Leave campaign, as proponents argued that until the UK had full control of its own immigration policy, it would not be able to handle the influx of European immigrants that arrive each year. However, according to the Office for National Statistics, of the 636,000 people who immigrated to the UK in 2015 only 270,000 were EU citizens. “Leave” voters also argued that immigrants were driving down wages in certain sectors and taking away many low-level jobs from British workers.

As for the economy, “Leave” voters claimed that Britain’s ties to the EU were preventing it from formulating trade relationships in emerging markets, such as China and India, where there is no major trade deal at present. Furthermore, these voters argued that leaving the EU would not affect London’s position as one of the world’s leading financial centers nor would banks relocate their headquarters. This is largely because Britain has very low corporate tax rates. Lastly, the Vote Leave campaign argued that an exit from the EU would mean that UK tax payers would no longer have to subsidize and bail out European countries that use the Euro and already have a majority in the Union. Instead, this money would be used to fund and support domestic issues such as the education system, NHS, and affordable subsidized housing.

“Remain” voters, however, argued that Brexit would seriously hurt UK trade levels and foreign direct investment. These voters believed that a decision to leave could prove extremely challenging for the UK, as it would sever the existing economic, social, and political relationships that it had with many EU nations. As for the question of jobs, the “Remain” side claimed that around three million jobs were linked to the EU which, if taken away, would destabilize the economy. Additionally, “Remain” voters insisted that businesses would be less likely to invest in the UK if they were not in the EU. This would be extremely disruptive because, according to a report by the Bank of England, foreign direct investment accounted for 10% of UK’s assets and liabilities in 2015 equaling around £10.6 trillion ($13.1M). The feeling of uncertainty surrounding Brexit was clearly felt in the UK’s financial market in the months leading up to the vote, as the Financial Times reported that UK investment declined by 2.1% in the final three months of 2015, despite growing by an average of 1.4% in the previous quarter.

UK Job Market on the Ballot

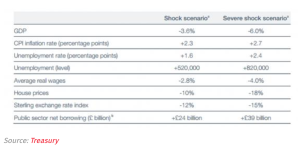

The implications of Brexit on the workforce was a key issue heading into the vote. Many economists argued that a decision to leave would trigger an economic downturn in the UK which could significantly weaken the British pound and lower employment levels. The British Treasury released a report in May 2016, which claimed that if Brexit were to happen, unemployment would be 520,000 higher, wages 2.8% lower and house prices 10% down. These statistics demonstrate why there was a high anxiety throughout the UK, as economists and citizens alike were trying to predict what the future of the UK may or may not look like.

However, because no other country had left the EU before there was no precedent for economists to compare the UK with. This meant that many of the arguments from both sides involved an element of speculation.

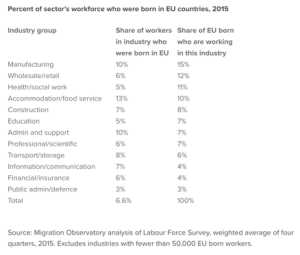

When the European Union was formed, it was created with the idea that there would be “free movement of labor” across all member nations. This meant that any citizen of the EU would be able to travel to Britain and seek employment without any formal job offer. Therefore, “Leave” voters viewed Brexit as an opportunity to gain back the jobs given to those immigrants and to increase national employment levels. According to research by Oxford University’s Migration Observatory, as of June 2016, there were 2.2 million EU workers in the UK composing for 6.6% of the total workforce.

The referendum drove voters to ask serious questions about long-term job security and availability. Would Brexit make it easier for young people to find jobs in the UK? Would wages increase as the result of a decreased supply of labor? What would happen to those jobs of migrants forced to leave? Where will the UK stand in terms of the international workplace?

Some economists predicted that in the short term, companies would choose to either transition their operations overseas or put a hold on hiring new employees until there was more economic certainty. The “Leave” campaigners argued that certain sector jobs, previously given to migrants, would now be available to British nationals.

However, there is very little evidence proving that immigration lowers wages or increases unemployment. According to Jonathan Wadsworth, an economist at the Center for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics, he says: “there is still no evidence of an overall negative impact of immigration on jobs or wages.” His claim was further supported research published by the UK Office for Budget Responsibility in 2015, which found that there was a small negative effect of migration on wages of workers in the semi-skilled and unskilled service sector such as shop assistants and restaurant and bar workers.

But do UK nationals really want those jobs?

While many argue that that Brexit will supply a large number of low-level jobs for UK nationals, the question must be asked of whether or not people are actually going to be willing to take them.

As seen below, EU workers are predominantly industry based with the manufacturing, retail, and health services accounting for the largest number of workers. Because the UK relies heavily on migrants to fill these low-skilled roles, the vote brought anxiety to employers in these industries, as they had to determine whether or not they will be able to fulfil their quotas if their workers were to be deported because of Brexit. While “Leave” campaigners argued that British nationals would seek these jobs if the referendum happened, “Remain” voters countered this by saying that British workers had not sought out these jobs before… so why would they now?

Amy Smith, a student at the University of Sheffield, expressed her concern, saying:

“Having grown up in Germany, I witnessed the benefits of immigration first-hand. Immigrants are vital for filling the low level positions German natives are less willing to take. I think the UK needs to recognize that the same implications can and will happen here.”

This issue was further discussed by economist Jonathan Porte, who described the demand for immigrant jobs as not being just a zero-sum game. In an article published by the Guardian he explained, “it’s true that, if an immigrant takes a job, then a British worker can’t take that job – but it doesn’t mean he or she won’t find another one that may have been created, directly or indirectly, as a result of immigration.”

Porte’s argument stands exactly opposite to that of the Vote Leave campaign, as he argues that a rejuvenation in the UK workforce will not occur simply by deporting migrants. Rather, it will happen with innovation and the exchange of ideas – which are a direct result of migration.

Current State of the Workforce

It has been four months since the vote, and economic numbers are showing more promise than expected. Although there was fear from the ‘remain’ voters that a decision to leave the EU would cause widespread job losses, economic data following Brexit is saying the opposite.

October figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that the UK unemployment rate remains steady at 4.9%, its lowest rate since 2005. According to the Guardian, this number remained unchanged since August, despite a 10,000 increase in unemployment.

Furthermore, the employment rate has remained at a record high of 74.5%. However, employment growth slowed from 173,000 in the three months leading up to July to 106,000 in August, with a large proportion of these being part-time workers.

So with these economic forces showing positive signs for the UK, does this mean that the workforce still has to worry?

Maybe not so fast.

While UK employment continues to rise, the country has seen a sharp rise in inflation which poses a major threat to job levels and wages. According to the ONS report, the UK’s inflation rate increased from 0.6% in August to 1% in September – the highest it has been since November 2014.

The issue of inflation is further exacerbated by the decreased value of the pound, which hit a new 31-year low against the dollar in October, and now exchanges at $1.22. This is largely driven by the uncertainty surrounding the terms of Britain’s exit from the EU, as financial markets lack confidence in the UK’s long term economic prospects.

An increase in inflation could potentially affect the UK’s unemployment rate going forward, as market anxiety can lead to decreased investment and lower economic growth in the workforce.

Furthermore, because the drop in the pound’s value has increased the cost of imports for British manufactures, certain sector jobs may be taken away as companies adjust to higher costs and decreased demand for goods.

But for now, until an official decision is made on Brexit’s terms, workers and immigrants across the UK must patiently wait… and hope that the decision to leave didn’t take their jobs with them.

SOURCES:

https://www.ft.com/content/953671ba-b784-37f6-8f29-45402e846d50

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/aug/17/uk-unemployment-claimant-count-falls-after-brexit

https://www.ft.com/content/3d0de756-1764-11e6-b197-a4af20d5575e

http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/why_vote_leave.html

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/06/28/brexit-will-foreign-investment-dry-up/

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/speeches/2015/euboe211015.pdf

https://www.ft.com/content/cca62354-e052-11e5-9217-6ae3733a2cd1

https://www.ft.com/content/0deacb52-178b-11e6-9d98-00386a18e39d

http://ukandeu.ac.uk/fact-figures/where-do-eu-migrants-in-the-uk-work/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.