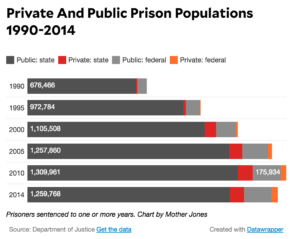

The United States incarcerates more people than any other country in the world, with approximately 2.2 million inmates behind bars in state, federal and private prisons across the country. That’s over half a million more inmates than in China, whose population is four times the size.

The Beginning of the Modern Private Prison Industry

The sharp increase in incarceration levels can be traced back to the 1970s, when the government struggled to combat the nationwide issue of drug-use and crime. When President Nixon declared a war on drugs in 1971, it forced an increase in tough policies against crime across the country.

In the two decades following 1980, the incarceration rate more than tripled, which led to major overcrowding in jails across the country. To tackle this issue, many states turned to private companies to build or run their prisons.

The first modern private prison was built in Tennessee in 1984 by the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA). Its opening marked the first time that any state government had contracted out the full operation of a prison to a private corporation.

What began as a quick-fix solution to the overcrowding of public prisons, the for-profit prison sector now accounts for 10% of the corrections market with an annual turnover of $7.4 billion per year.

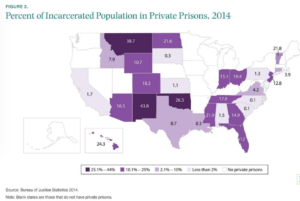

As of 2013, the US Department of Justice reported that 19.1% of the federal state prison population is housed in private prisons along with 6.8% of state prisoners. Today, there are over 130 for-profit prisons with 157,000 beds and this number is expected to reach 360,000 by 2026.

For-profit prisons are legal in 29 states across the country with some relying predominantly on private facilities to house their inmates. For example, nearly 44% of all New Mexico prisoners are held in private prisons, followed by 38.7% in Montana.

While the rate of violent crime in the United States has fallen by about 20% since 1991, the number of people in prison or jails has risen by 50%, as roughly 13 million people are sent to jails in any given year.

But how does that make sense?

Proponents against private prisons argue that the contracting of prisoners has created an economic incentive to put people behind and because of this, for-profit prisons rely on the incarceration of prisoners to keep their corporations afloat and their stockholders happy.

Private Industrial Complex

This complicated intersection of public and private interests is known as the “prison-industrial complex”. The term was created to explain the correlation between the rapid expansion of the United States’ inmate population and the influence of private prison companies that house and supply labor to government prison agencies.

The corporations who operate under this title include construction companies, surveillance technology providers, private probation companies, lobby groups, and even prison cafeteria vendors. This complex, however, has become highly controversial, as the economic and social implications of “contracting out” prisoners to private companies has placed the privatization of prisons at the forefront of American politics.

The prison-industry complex is one of the fastest growing industries in the United States, with private prisons accounting for the largest business in the group.

Why Support Private Prisons?

The main argument for establishing private prisons is that they can provide correctional services more efficiently and for a lower price than the government itself. This is because they do not have to compete directly with other state penitentiaries for contracts and are able to decide on the types of inmates that they will house. Similarly, those in favor argue that they provide a financial solution that prevents the government from having to invest major capital into building new prisons and providing other benefits such as pensions, salaries, and health-care.

Supporters of this industry argue that private prisons are more advantageous for American taxpayers, as for-profit owners have more incentives to find efficient practices and lower overall costs. Furthermore, private prison corporations claim that building new facilities generate income for surrounding communities as they create jobs and receive tax revenues.

Arguments Against Private Prisons

However, the validity of these arguments are hard to confirm, as an evaluation of 24 independent studies on the cost-effectiveness of public vs. private prisons found that for-profit institutions were no more cost-effective than public ones. Instead, the report suggests that the most important factors in determining a prison’s daily cost per inmate are the facilities economy of scale, age, and security level. A 2011 report by the American Civil Liberties Union also found that in addition to influencing mass incarceration levels, private prisons are more expensive, more violent and less accountable than public ones.

Since private prisons are created to be more cost efficient than public ones, it is common for them to have lower staffing levels and training than their counterparts. This links to the argument that violence against guards tends to be higher, as a nationwide study found that assaults on guards were 49% more frequent in private prisons than in those run by the government.

The key arguments against the establishment of for-profit prisons are that they are not run with safety in mind, they harm minorities, they create financial incentives to incarcerate and they corrupt the political process. They argue that firms in the prison business reap profits by billing the government more than is needed and find alternative ways to lower costs which can make prisons less secure.

Secondly, it is argued that for-profit prisons marginalize minority groups, as according to a report by the Justice Policy Institute, private companies hold nearly half of the nation’s immigrant detainees. This is double the rate that it was nearly a decade ago.

Policy, Politics, and Problems

Moreover, political corruption and the influence of corporations on federal detention policies have become an area of major contention. Because private prisons are for-profit, many of them are funded and invested in by national corporations, investors, and politicians.

Of both public and private correction systems, Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) operates the 5th largest in the US and has 51 owned-and-operated facilities in 16 states and 18 state-owned facilities in 7 states. Their large market share provides them with a staggering market cap of over $3 billion and reported revenues of $1.84 billion in 2015. Likewise, the 2nd largest private corporation, GEO group, reported $1.79 last year.

So how much political influence do these corporations have?

According to a report by the Justice Policy Institute, private prisons increase their political influence through lobbying, direct campaign contributions, and building relationships and networks. This notion is supported by the fact that both corporations have funneled more than $10 million to political candidates since 1989 and have spent nearly $25 million on lobbying efforts.

Lobbying is a key reason why these for-profit correction corporations have been able to achieve such high margins, as their efforts have influenced government at all levels to underwrite private prison expenses and to pass laws that ensure certain levels of beds will be filled at each prison…also known as an incarceration quota? For example, in 2015 CCA and GEO lobbied for a Congressional mandate that required 34,0000 immigration detention beds be maintained and paid for with tax dollars.

Due to lobbying efforts, these corporations are also exempt from taxpayer oversights, as they have been excluded from the federal disclosure system under the Federal Freedom of Information Act, which denies public access to private prison operation records.

In an interview with the LA Times, Alonzo Peña, former director of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement from 2008 to 2010 said, “he had long been concerned that for-profit prison companies had been hiring former immigration official to help them secure favorable contract terms.” This is extremely problematic as manipulating the system through contracts allows the corporations to be exempt from following governmental standards and protocol.

So if the government is not responsible for keeping watch on these private prisons…who is?

The haziness between what is legally acceptable and followed by these private prisons continues to cause controversy in the US, as the government’s level of jurisdiction over these corporations becomes increasingly unclear.

What was created as a short-term solution to combating overpopulation has developed into a multi-billion-dollar industry where investors are pouring their money into these corporations’ stocks to watch the value go up on the stock exchange.

However, the tradeoff between public and private interest doesn’t seem to balance…

More inmates? More Money?

A life-sentence for a stock?

That sounds like democracy…right?

SOURCES:

http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-prison-industry-in-the-united-states-big-business-or-a-new-form-of-slavery/8289

http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2010/08/private_prisons

http://greengarageblog.org/5-foremost-pros-and-cons-of-private-prisons

http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/21694-shocking-facts-about-americas-for-profit-prison-industry

https://www.propublica.org/article/by-the-numbers-the-u.s.s-growing-for-profit-detention-industry

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/bernie-sanders/we-must-end-for-profit-pr_b_8180124.html

http://cad.sagepub.com/content/45/3/358

https://smartasset.com/insights/the-economics-of-the-american-prison-system