Being a “shopping consultant” in Australia has potential to earn great returns thanks to the steady high demand coming from the Chinese customers. As an article on Business Insider introduced, Chinese students living in Australia can make up to $3000 a week by selling Australia made health products, such as vitamin and baby formula. Today, shopping consultant has become an alternative to those who do not commit to a full-time job.

Demand for health products made overseas started to rise since China’s Baby Formula Scandal in 2008. Chinese company Sanlu Group was found responsible for producing infant formula adulterated melamine, causing six infants die from kidney stones and about 54,000 infants diagnosed with kidney damage. The scandal led to a long-term national criticism on food safety. Today, when it comes to buying baby formula, traumatized parents still wouldn’t consider products made in China as their first choices.

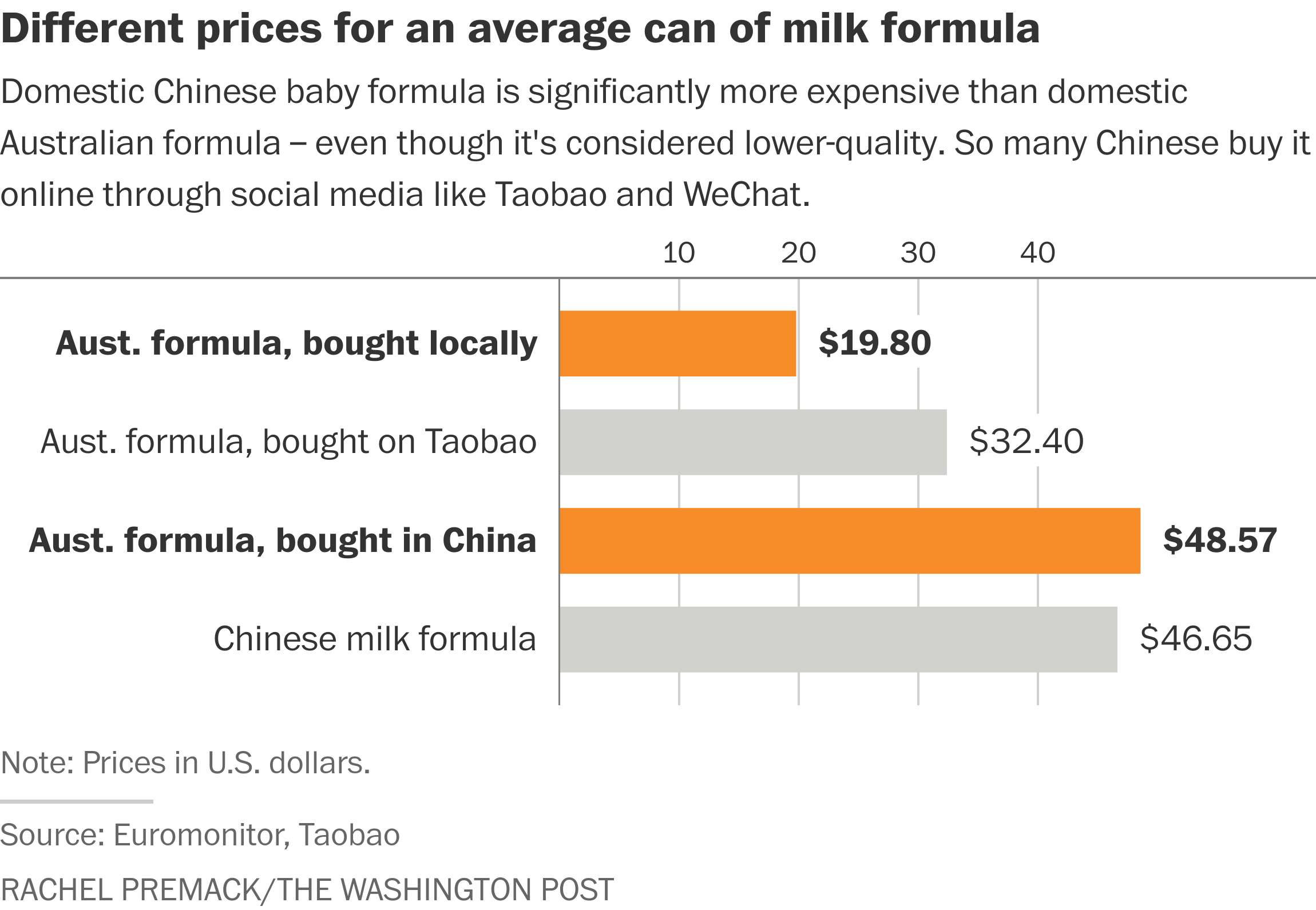

Since than, many Chinese customers turned to baby products that are made in other countries. Australian product has a great reputation in terms of safety and quality, so it becomes one of the top choices among the Chinese consumers. But the prices of import products at retail stores are often much higher — usually double than the products sold in Australia. One can of formula which costs about $20 in Sydney, can end up charging customers $48 at the retail stores.

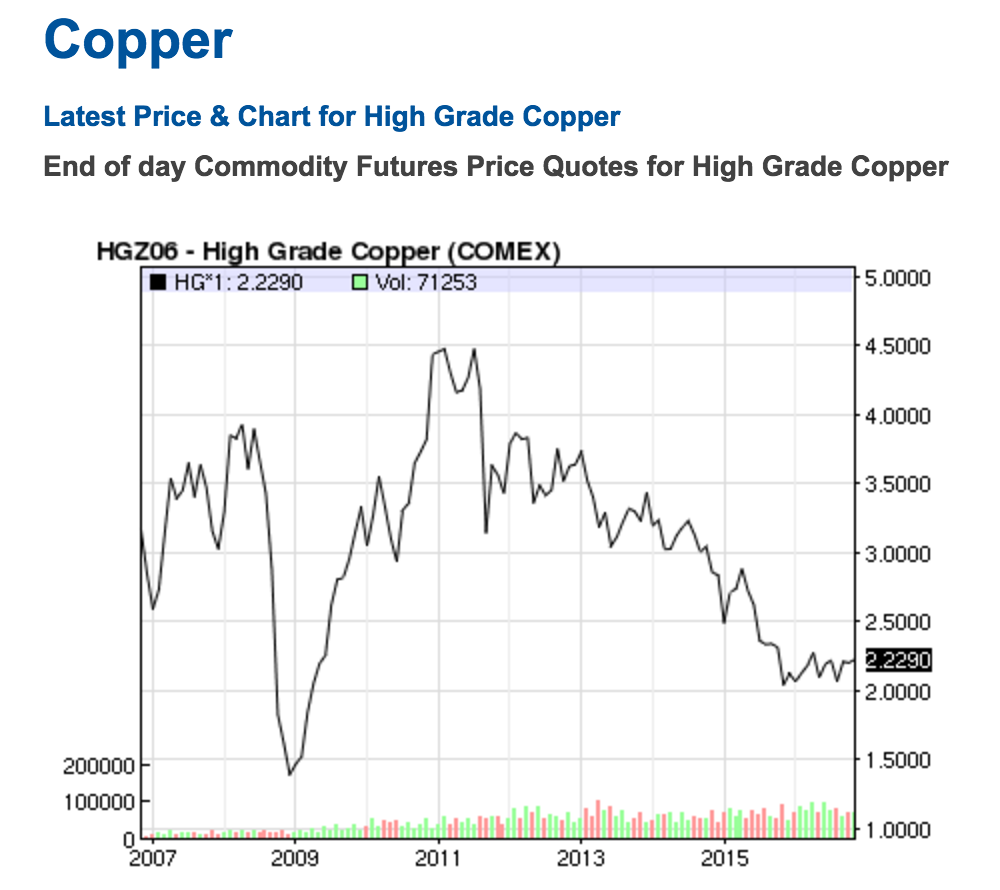

That’s when some Chinese living in Australia started to realize the business opportunity. In addition to the sudden raise of demand, a heavy drop in Australian dollar also prompted benefit for this new career. According to Yahoo, in July 2008, one AUD equals to approximately 6.5 Yuan. However, that same Australian dollar could only buy 4.5 Yuan by Mid October, 2008. It was great news for both Chinese consumers and shopping consultants in Australia, because within three months, all products made in Australia became cheaper by almost a third.

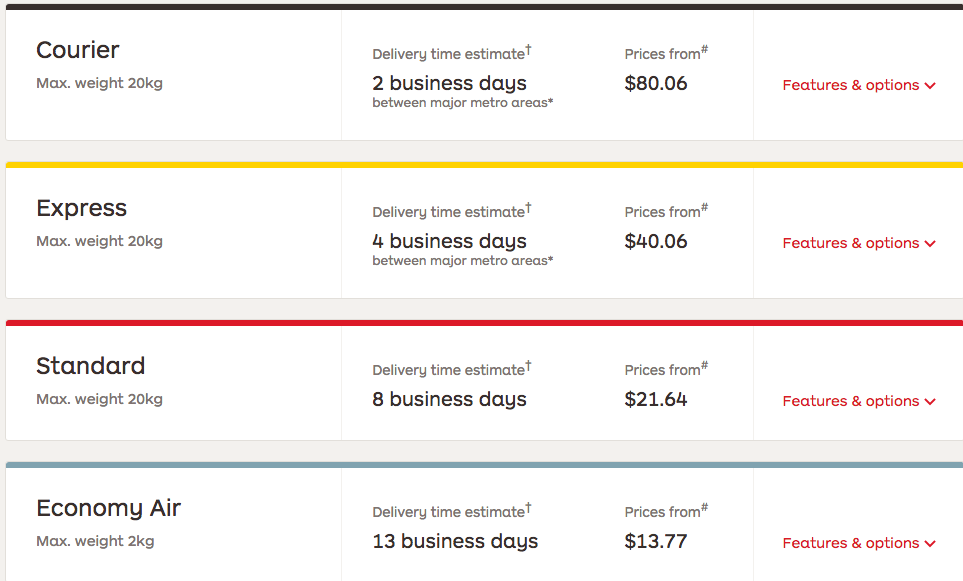

Demand for Australian baby formula started to raise dramatically. Some Chinese live in Australia saw it, and decided to start a business. The shopping consultants take requests from the Chinese customers, and buy baby formula from Australian stores. They distribute products in different ways. Some set up online stores on platforms such as Taobao and WeChat; so communicate with customers via WeChat and ship products directly through custom. The expensive international shipping cost is the biggest challenge for these shopping consultants. For example, the Australia Post’s pricing for international standard shipping starts from $21.64 a kilogram. It is essential for shopping consultants to find cheaper shipping alternatives.

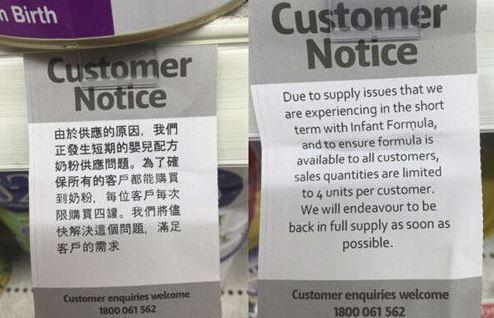

The rapid growth of Chinese demand for led to a shortage in Australian baby formula supply. Supermarkets begin to limit the amount of cans each person could buy.

However, a change in Chinese custom and e-commerce ruling announced in April this year has led shopping consultants to a greater challenge. They now have to pay for a higher import tax on products — on postage items, passenger carry-on items, as well as foreign e-commerce transactions. While the revenue is being threaten, they are also facing a competition. Some Australian baby formula producing companies have set up official online stores on Chinese e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Jingdong. The value of RMB has also been gradually increasing since the end of May this year (1AUD=5.18 Yuan, Nov.1st, 2016). Perhaps the good times for full-time baby product shopping consultants are finally coming to an end.

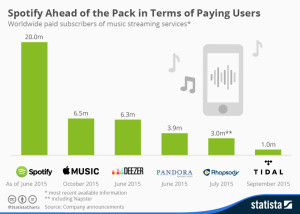

Although there are many various streaming companies currently in the market, they all offer slightly different benefits for the consumer and attract different sectors of the population.

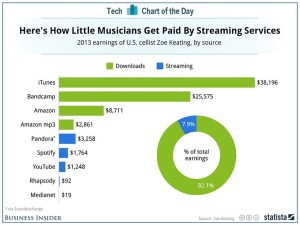

Although there are many various streaming companies currently in the market, they all offer slightly different benefits for the consumer and attract different sectors of the population. uge revenue stream, with annual payouts ranging from $100,000 to $500,000 per year. However, for the small artists who might only have a few thousand fans on Spotify or Apple Music, this can threaten their survival in the business

uge revenue stream, with annual payouts ranging from $100,000 to $500,000 per year. However, for the small artists who might only have a few thousand fans on Spotify or Apple Music, this can threaten their survival in the business

remixes and unofficial music, is the next purchase for Spotify. This could be beneficial, as SoundCloud needs help financially and the purchase would diversify Spotify’s catalogue, as it would include more original content and more indie label releases.

remixes and unofficial music, is the next purchase for Spotify. This could be beneficial, as SoundCloud needs help financially and the purchase would diversify Spotify’s catalogue, as it would include more original content and more indie label releases.

Former nomads settle in their gers near mines to find work.

Former nomads settle in their gers near mines to find work.