Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.

Dorothy and her travel companions didn’t listen, of course, and peeked behind that curtain to find out that the great wizard was just a man with a machine. The financial industry is experiencing the inverse, as it examines a machine that is run by a “man” who does “his” best to avoid existing.

More than 30 of the largest banks in the world are digging into what has been one of the most vexing technological advances of the past decade—the emergence and rise of bitcoin, the world’s most famous (or infamous) cryptocurrency, which was created by an individual under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto.

With an etymology tied to the Greek word “kruptos” which means “hidden,” it’s not surprising that outside of a handful of techies and economists, cryptocurrencies are not well understood. However, for the first time, mainstream finance is taking notice of cryptocurrencies and trying to harness their algorithmic backbone—known as blockchain technology—before it challenges the entire industry’s structure by completely disrupting payment and banking.

Background on bitcoin and cryptocurrency

The main questions here are:

- What, exactly, is it?

- Who uses it?

- Where did it come from?

What is bitcoin?

At its most basic form, a cryptocurrency is a digital medium of exchange that is regulated solely by computer coding. Algorithms determine both the creation of new units and the security of transactions made in the units already in circulation. The alpha of this virtual market, of course, is the anarchic, open-source, peer-to-peer (P2P) “currency” bitcoin, which came into existence under ambiguous circumstances—more on that in a second—in 2009.

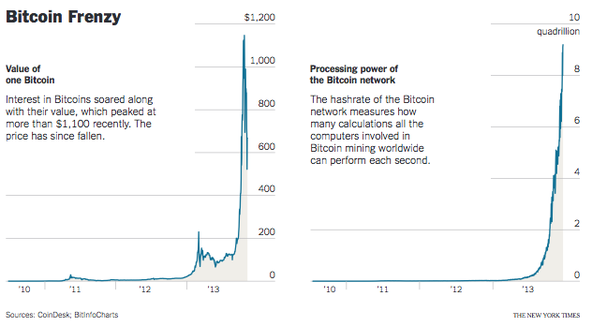

Bitcoin operates by controlling supply. Its algorithm is set up to distribute 21 million units over the course of 10 years, so its value is determined solely by demand, which has grown over the first five years of its existence. Its value peaked in late 2013, reaching a value of more than $1,100 amid a corresponding spike in the amount of compute power dedicated to “mining” for new units.

Of course, the cause of the demand and compute power spikes is an increasing number of people investing an obscene amount of money into unlocking new blocks of bitcoin, thereby pricing out much of the digital money’s previous user base of currency aficionados and hobbyists.

Who uses it now?

The second question of who uses bitcoin is where the story begins to get considerably more complicated. The short answer is that no one knows, exactly. Without a central regulator akin to the Federal Reserve or the International Monetary Fund, transactions are monitored by a distributed ledger, which is basically an algorithm that shares every proposed transaction with every node in the bitcoin network. The result is complete anonymity as transactions being placed into blocks that every bitcoin-capable machine can see and verify without shedding any light on the individuals or entities carrying out these transactions.

While transactions are secure in and of themselves, the lack of transparency into who is using this anonymous digital monetary system has made bitcoin a lightning rod in broader discussions about national/international security and criminal activity. Most notably, the anarchist founder of the online narcotics hub Silk Road was an early adopter and evangelist for bitcoin—not exactly an ideal advocate for a technology struggling to find mainstream success.

Nonetheless, illegal as Silk Road’s activities might have been, they were a huge source of bitcoin’s visibility and, thus, the primary driver of its demand-determined value.

When it comes to ambiguity, though, end users aren’t the only part of bitcoin that has been shrouded in mystery. The very source of the world’s preeminent cryptocurrency had been nothing more than a pseudonym—until last week.

Where did it come from?

From recent coverage in Wired and Gizmodo, it appears that the man behind the bitcoin curtain is a 44-year-old Australian named Craig Steven Wright, who “coincidentally” had his home and office raided by the Australian Taxation Office just this week. While authorities claim that the raid had nothing to do with the news that Wright was, in fact, the mysterious Nakamoto, the timing is certainly curious, and the fact that the bitcoin founder’s fortune is estimated by some to exceed $415 million certainly does not support that it is coincidental.

Regardless, the mystery appears to be solved, and no one seems to be debating the value of bitcoin now. In fact, a whole new set of stakeholders has emerged and is taking a good, hard look into its enabling technology—blockchain.

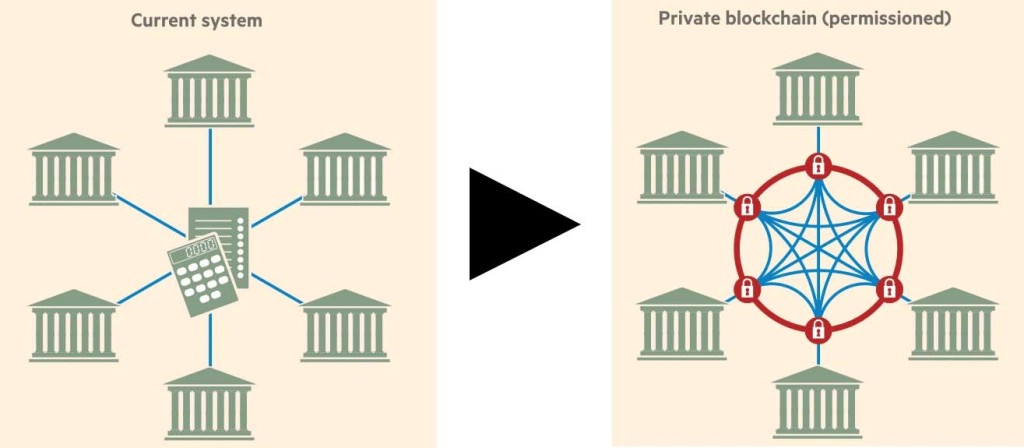

Taking blockchain mainstream

While they’re not interested in using bitcoin as is, 30 of the largest banks in the world are working as part of a collective evaluating whether or not its enabling blockchain technology and the distributed ledger it creates have wider-reaching uses within the financial services industry. This collective is operated by R3 CEV, a global financial tech company comprised of veteran financial professionals, technologists and tech entrepreneurs.

“This partnership signals a significant commitment by the banks to collaboratively evaluate and apply this emerging technology to the global financial system,” said David Rutter, CEO of R3. “Our bank partners recognize the promise of distributed ledger technologies and their potential to transform financial market technology platforms where standards must be secure, scalable and adaptable.”

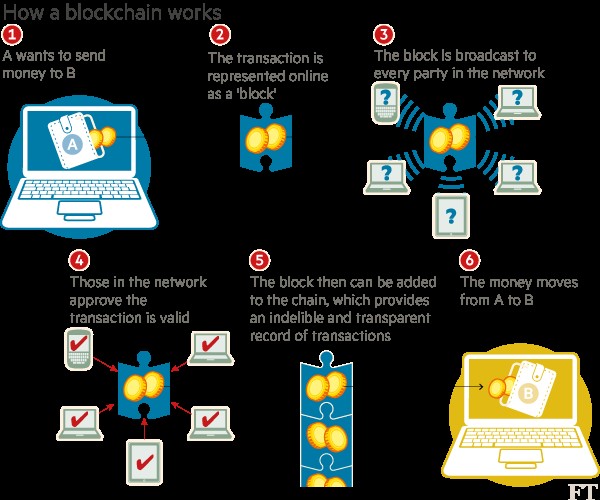

In comparison to the other aspects of bitcoin, the blockchain and distributed ledger concept is fairly simple. When one user pays another in bitcoin, the transaction is known as a block and is announced to every node (compute device loaded with the appropriate software) on the bitcoin network. Every node then approves the block, which is added to a “chain” of other blocks, creating a running record of every transaction across the entire network. With every node in the network verifying every transaction, in real time, the entire system remains self-regulating.

The collective takes it as truth that some form of this blockchain and distributed ledger is going to become the norm in the banking industry but is looking to establish the necessary standards and protocols—common practice for an emerging technology that necessitates interoperability across multiple platforms (or in this case, the entire financial industry). These banks are essentially trying to implement this technology to virtualize their transactions with each other—analogous to businesses moving to the cloud as opposed to storing every bit of data on their own servers.

While the potential cost savings and scalability improvement are obvious from an infrastructure standpoint, it’s less clear how much additional investment would be required to perform the necessary network upgrades to increase reliability and security to meet the standards of the highly regulated finance industry.

“Right now you’re seeing significant money and time being spent on exploration of these technologies in a fractured way that lacks the strategic, coordinated vision so critical to timely success,” said Kevin Hanley, Director of Design at Royal Bank of Scotland. “The R3 model is changing the game.”

Furthermore, “the game” being changed has expanded into the way financial markets operate with banks frequently facing the question of how technologies such as cryptography and distributed ledgers can contribute to improvements.

“These new technologies could transform how financial transactions are recorded, reconciled and reported – all with additional security, lower error rates and significant cost reductions,” said Hu Liang, Senior Vice President and head of Emerging Technologies at State Street. “R3 has the people and approach to drive this effort and increase the likelihood of successfully advancing the new technology in the financial industry.”

Assuming this implementation is as inevitable as the R3 collective believes, the next question becomes one of how far the technology might go.

Disruptive potential

The holy grail for a new technology (or, in this case, the reemergence of an existing one), can be boiled down to one of the tech industry’s favorite buzzwords: disruption. Everyone wants to know what this technology is capable of doing to upend the way business is done.

The potential implications of blockchain and distributed ledgers as they pertain to transactions in commercial banking are intuitive, but as Liang and others have alluded to, these technologies threaten established practices well beyond.

Coincidentally, around the same time bitcoin was emerging, investment banks and other financial entities were engaged in an arms race to maximize compute power and, therefore, the speed with which they received information about the markets. Just as computers replaced phone calls and turned minutes into seconds on the trading floor, high-performance computer power was turning seconds into fractions of seconds, providing the edge to those who get the information first—even if that lead time is literally the blink of an eye.

The compute power is still of vital importance, and virtualizing the ledger process would theoretically speed up transactions even more by freeing bandwidth that could be reallocated to processing incoming data.

On a more micro level, the best disruption analogy is third-party payment services, which offered the first viable set of alternatives to cash or credit. PayPal gave users the first option for decoupling their bank accounts or credit cards from their online purchases. Mobile payment services from Google and Apple took this concept to smartphones, and Venmo extended it to person-to-person transactions.

Blockchain and its associated capabilities can have a similarly disruptive effect by redefining the process by which these transactions take place. By being agnostic to the endpoints of the transactions, the technology would eliminate the need for a payment company to be in the middle of every transaction.

Of course, the major question that remains as to how to get the different players in a competitive market to work together to develop the level of interoperability necessary to make this blockchain-backed ledger system a reality—a tall order, indeed.

When’s the last time Google and Apple worked together to make something interoperable?

It was certainly longer ago than the current collaboration among Bank of America, Wells Fargo and 28 of their competitors. Raise your hand if you ever thought of a scenario in which banks were more visionary than tech companies.

That might be the real magic trick.

The American movie theater business is in a state of flux. Theaters are scrambling to come up with fresh ideas and marketing strategies aimed at attracting more people to their establishments. Digital technologies like 3D and IMAX formats have pushed theaters to increase ticket prices over much of the last decade. Finally, the growing popularity of streaming services, like Netflix and Amazon Prime, have given people across the country easier access to entertainment. Before the advent of new and emerging entertainment platforms, movie theaters provided many people with an escape from reality. Today, it remains questionable whether the industry has the same influence it once had over the entertainment world. Major chains like Regal Cinemas and AMC now face the challenge of updating their business plans and reminding the public why the movie theater experience is not going anywhere.

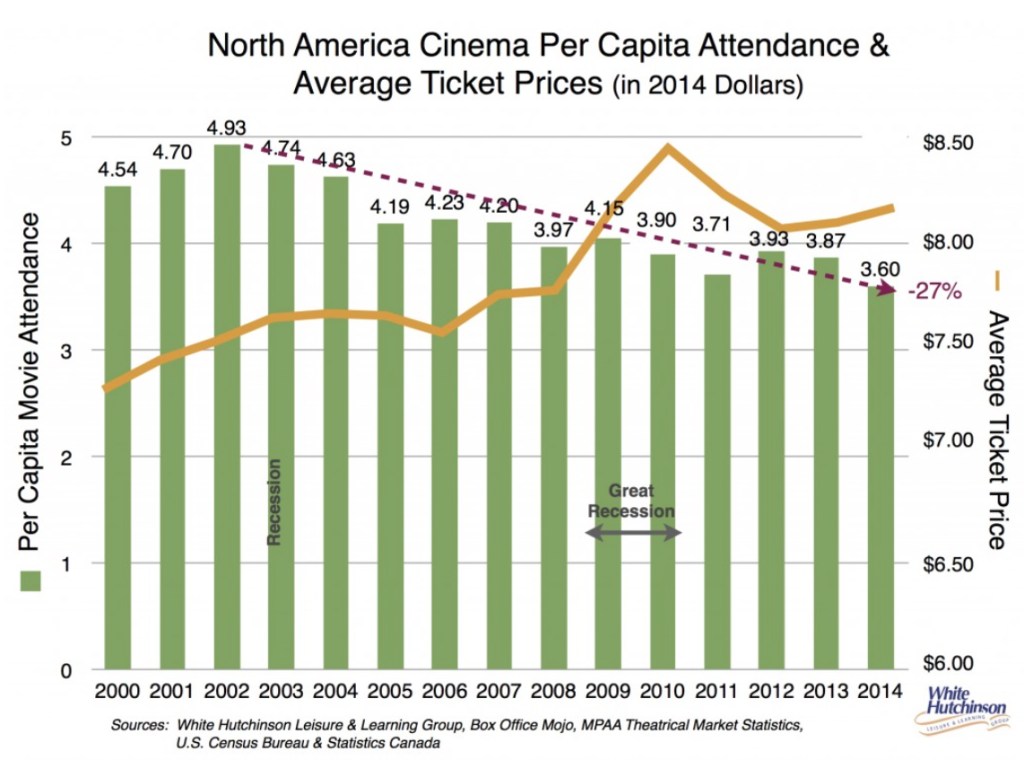

The American movie theater business is in a state of flux. Theaters are scrambling to come up with fresh ideas and marketing strategies aimed at attracting more people to their establishments. Digital technologies like 3D and IMAX formats have pushed theaters to increase ticket prices over much of the last decade. Finally, the growing popularity of streaming services, like Netflix and Amazon Prime, have given people across the country easier access to entertainment. Before the advent of new and emerging entertainment platforms, movie theaters provided many people with an escape from reality. Today, it remains questionable whether the industry has the same influence it once had over the entertainment world. Major chains like Regal Cinemas and AMC now face the challenge of updating their business plans and reminding the public why the movie theater experience is not going anywhere. In 2002, the average American went to a movie theater 4.9 times per year. In 2014, the number dropped to 3.6 times per year. Decreasing attendance has been a major factor in the decline of the old movie theater business model. According to CEO Randy White of the White Hutchinson Leisure and Learning Group, the last twelve years of per capita movie attendance had a steady drop of over 25 percent. The 2014 calendar year had only 1.26 billion consumers buying movie tickets which comes dangerously close to the 1.24 billion consumers seen in 1994. Overall, theater attendance does fluctuate every year, but the steady decline paints a negative picture of attendance in the long term.

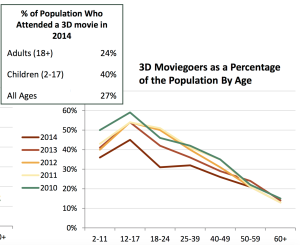

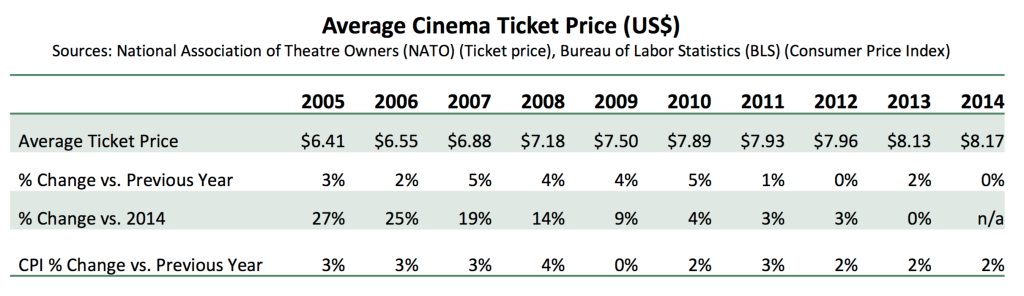

In 2002, the average American went to a movie theater 4.9 times per year. In 2014, the number dropped to 3.6 times per year. Decreasing attendance has been a major factor in the decline of the old movie theater business model. According to CEO Randy White of the White Hutchinson Leisure and Learning Group, the last twelve years of per capita movie attendance had a steady drop of over 25 percent. The 2014 calendar year had only 1.26 billion consumers buying movie tickets which comes dangerously close to the 1.24 billion consumers seen in 1994. Overall, theater attendance does fluctuate every year, but the steady decline paints a negative picture of attendance in the long term. In its most recent annual theatrical statistics report, the Motion Pictures Association of America emphasizes the dramatic decline in 3D movie attendance as another culprit. On average, 27 percent of the population went to a 3D movie in 2014, but the numbers for different age groups have all dropped between 5 to 10 percent since 2010. Since the arrival of Avatar in 2009, the U.S. film studios have hoped to replicate its success; however, the push to make more films in 3D might be losing steam mainly because it costs too much to make, which has an adverse effect on ticket prices.

In its most recent annual theatrical statistics report, the Motion Pictures Association of America emphasizes the dramatic decline in 3D movie attendance as another culprit. On average, 27 percent of the population went to a 3D movie in 2014, but the numbers for different age groups have all dropped between 5 to 10 percent since 2010. Since the arrival of Avatar in 2009, the U.S. film studios have hoped to replicate its success; however, the push to make more films in 3D might be losing steam mainly because it costs too much to make, which has an adverse effect on ticket prices.

It is hard to avoid the rise in online streaming services as a major reason why movie theaters are scared about the future. In October of this year, streaming giant Netflix released its own feature-length film called Beasts of No Nation. This film marked the second time the company released a movie online as well as in the theaters, which did not make exhibitors very happy. In an article from Variety, the four largest theater chains – Regal, AMC, Cinemark, and Carmine – announced they would not show the film because it did not follow the ’90-day delay rule’ between theatrical and home release. They do not see the the release of the film on various platforms as fair to any theater chain around the country.

It is hard to avoid the rise in online streaming services as a major reason why movie theaters are scared about the future. In October of this year, streaming giant Netflix released its own feature-length film called Beasts of No Nation. This film marked the second time the company released a movie online as well as in the theaters, which did not make exhibitors very happy. In an article from Variety, the four largest theater chains – Regal, AMC, Cinemark, and Carmine – announced they would not show the film because it did not follow the ’90-day delay rule’ between theatrical and home release. They do not see the the release of the film on various platforms as fair to any theater chain around the country.

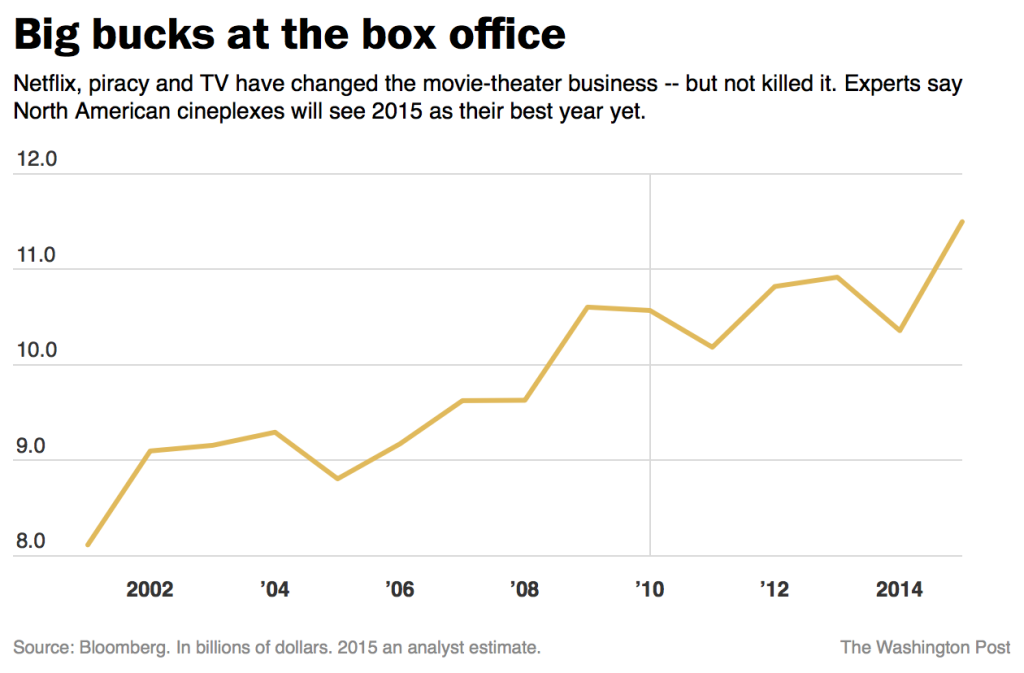

The revenue trends from the last twelve years, courtesy of analysts from Bloomberg, show how film business experts project revenue for the movie theater business to reach approximately $11.5 billion this year. The business seems to still be alive and companies are starting to notice what makes the average consumer want to come back again and again: incentivization.

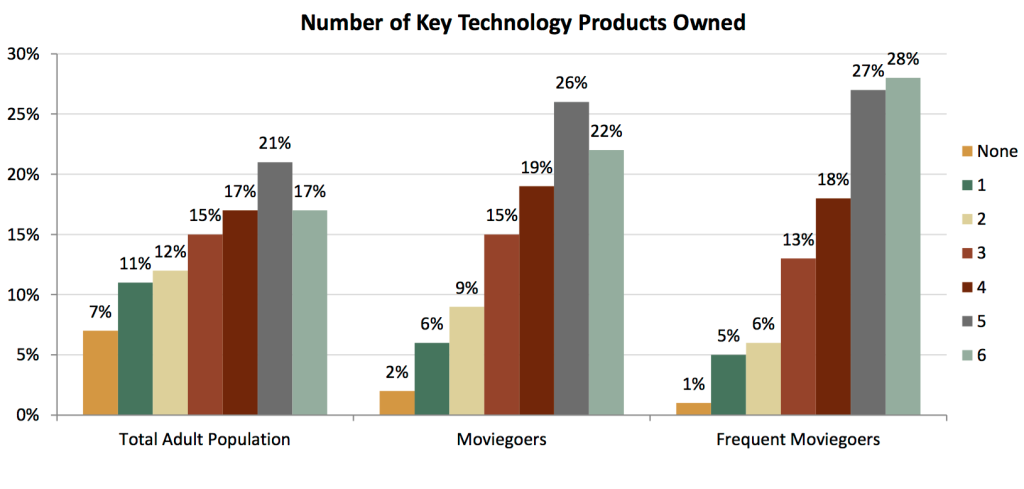

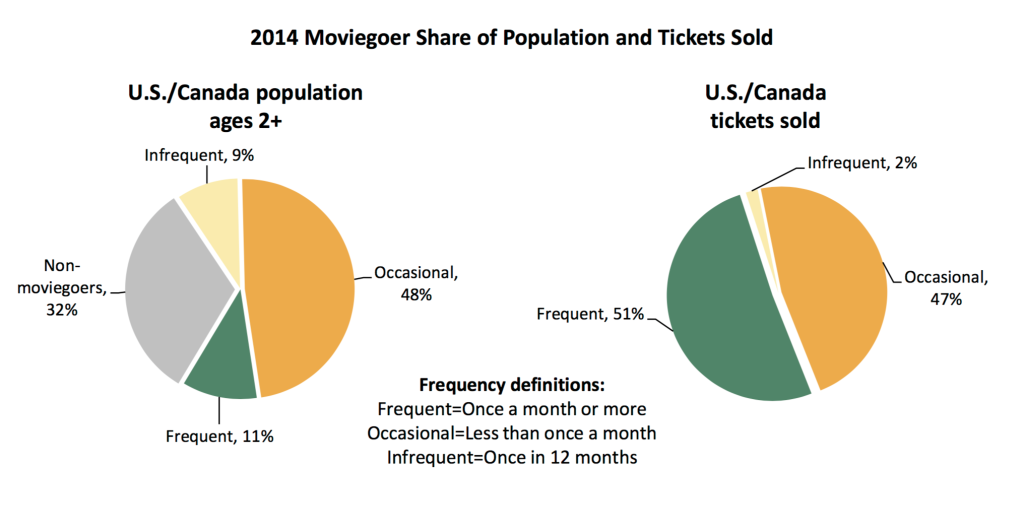

The revenue trends from the last twelve years, courtesy of analysts from Bloomberg, show how film business experts project revenue for the movie theater business to reach approximately $11.5 billion this year. The business seems to still be alive and companies are starting to notice what makes the average consumer want to come back again and again: incentivization. The MPAA says 11 percent of people in the U.S and Canada were frequent moviegoers in 2014, yet those same people made up over 51 percent of tickets sold. This information correlates with the increasing price of tickets: Film buffs are the people most willing to pay to see multiple movies over the course of the year, so they would likely make up a sizable amount of the tickets sold.

The MPAA says 11 percent of people in the U.S and Canada were frequent moviegoers in 2014, yet those same people made up over 51 percent of tickets sold. This information correlates with the increasing price of tickets: Film buffs are the people most willing to pay to see multiple movies over the course of the year, so they would likely make up a sizable amount of the tickets sold.