When the phrase “world domination” is used in reference to a powerful entity, the first image that often comes to mind is a villain in a cartoonish suit who absorbs power as the surrounding world crumbles — sometimes even accompanied by evil-sounding thunder in the background. World domination, however, is not limited to unrealistic individuals who wear masks that shield their true identities from being associated with their heinous crimes. Instead, the modern-day world dominator takes on a more digital form, making their tactics easily accessible to the public by interacting with their followers on a daily basis. As loyal followers build trust in the entity, individuals are more willing to divulge information as the power source grows in influence, teaching the dominator to tactfully increase its followers based on previous behavioral patterns. The cycle repeats until the dominator has created such a large presence that its followers literally cannot go about their day-to-day lives without it but, even worse, don’t really question this codependency.

Yes, Amazon and Facebook are the culprits of world domination — or, at least, they’d like to be.

The digital sphere as the modern world knows it has only been in existence for about two decades but has completely revolutionized the way humanity functions. Twenty years may be an extremely short period relative to all of time, but this small sliver of time has seen unprecedented societal and economic progress that has rewired the way we consume goods, interact with others and even perceive ourselves. This progress will only continue to exponentially grow, and digital companies like Amazon and Facebook will play a vital role in evolving our economic choices alongside forming our digitally-dependent society.

On one hand, the accessibility and connectivity Amazon and Facebook provide have made experiencing life in the 21st century easier than ever before between instant communication with peers and having nearly anything imaginable delivered right to one’s doorstep with the click of a button. As mentioned earlier, however, people unquestionably are becoming increasingly co-dependent on these large digital companies to live their everyday lives and make economic decisions — emphasis on unquestionably. While individual consumers make their lives easier by passively allowing these massive digital entities to become interwoven in their lives, the dominance of Amazon and Facebook on a grander economic scale may prove more dangerous than anticipated.

Primarily, the superiority Amazon has over specific producer markets and the dominance Facebook has over advertising are reminiscent of Standard Oil’s monopoly on oil in the late 19th century. By owning or controlling 90 percent of the U.S. oil refining business, Standard Oil was able to form trusts with other oil companies and drive out competition with others in the same business. Though Standard Oil was able to provide a good quality product at a reasonable, stable price, the company, from the government’s perspective, uncomfortably wielded too much power in one of the nation’s most important industries. Ultimately, the government put antitrust laws into practice, breaking down Standard Oil’s trust and, ideally, preventing further monopolies from forming.

Now in the digital age, the large-scale presence of Amazon and Facebook isn’t as tactile as, say, oil, but that doesn’t mean their potential to monopolize isn’t as — if not more — dangerous. The way consumers interact with these companies may be limited to a screen, but their impact is both felt and seen in the real world.

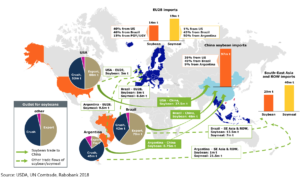

Amazon, as most any digitally literate citizen knows, is an online retailer that consumers can utilize to buy nearly anything — anything — and have it shipped to their door. As discussed by Jonathan Taplin in his book “Move Fast and Break Things,” Amazon has created a monopsony over certain goods, which is essentially the inverse of a monopoly. A monopsony, according to Taplin, is when a buyer, as opposed to a seller in a monopoly, has control over who can enter a specific market to buy goods, which drives prices down.

“Amazon has a near-monopoly position in the distribution of ebooks,” Taplin writes. “Beyond books, Amazon captures fifty-one cents of every dollar Americans spend in online commerce. It wasn’t supposed to be this way.”

Ironically, in 2014, New York Times opinion writer Paul Krugman published an article titled “Amazon’s Monopsony Is Not O.K.,” where Krugman claimed that “Amazon doesn’t dominate overall online sales, let alone retailing as a whole, and probably never will.” Come 2018, research by eMarketer tells an updated story: Amazon now shares 49.1 percent of retail ecommerce sales, which is nearly 5 percent of the total U.S. retail market online and offline.

Further, Taplin points out that the main consequence of Amazon’s monopsony in the book business forces authors and publishers to work for less money. He details how Amazon is able to practice a form of “rent-seeking” by denying publishers access to its large customer base and extracting excessive “rents” from publishers because the company has driven out seller competition. Arguably, Amazon’s path to digital retail dominance came rapidly and without much question because of the convenience the company brought to consumers. As a result, however, the consequences of Amazon’s presence are only recently being felt and studied.

“Monopsony power has probably always existed in labor markets, but the forces that traditionally counterbalanced monopsony power and boosted worker bargaining power have eroded in recent decades,” writes Alan Krueger of the Princeton Economist.

VIDEO: Here’s Amazon’s impact on the economy

Beyond damaging competition with selling in the book market, Amazon has established other monopsonies that have had disastrous effects for classic physical retailers.

“Amazon has changed the market in many ways. By the end of this week, Sears will file for bankruptcy. That’s a direct result of Amazon. Kmart will file for bankruptcy probably within the next two months. There’s really no place for the old-fashioned retail to exist in a world where Amazon can undercut their prices,” said Taplin in an interview. “Amazon wants to rule the world. It’s simple.”

Facebook is a whole other beast.

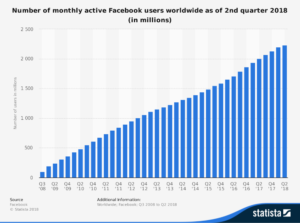

As mentioned, Amazon holds a monopsony over particular retail markets, like ebooks. This makes it harder for other buyers to enter the market because Amazon’s prices are so competitive that any smaller buyer would have a hard time being successfully profitable. Facebook, on the other hand, is the largest social network in the world with over two billion monthly active users or “MUAs.” The platform also owns Instagram and WhatsApp, which each have over a billion MUAs.

Facebook’s increasing MUAs from 2008-2018, according to Statista.

With such a large reach in the social media realm, Facebook has a near monopoly on affinity-side advertising, according to Dan Faltesek’s Medium article “Social Monopsony.” Taplin discusses Facebook’s business model in the same light, noting that the platform centers around selling advertising at a higher rate than comparable internet sites.

“In short, if you are looking to make a large social buy, Facebook is your only option,” writes Faltesek. “The case that Facebook has a near monopoly on in-stream affinity network advertising is fairly clear.”

Why is Facebook’s advertising scheme so successful? It’s simple: Microtargeting.

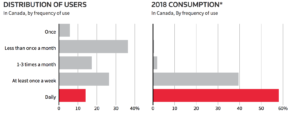

Microtargeting is a marketing strategy by which a company collects specific information on consumers — where they live, what they like, what their friends like and so forth — and pushes advertising content their way that directly reflects their specific interests. While this can be an effective strategy for marketers, in a world where there is only one buyer of user attention, regulation is necessary, as Faltesek points out.

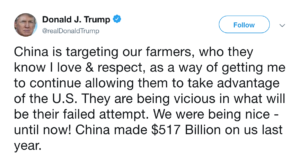

So where does this leave modern society? For how much longer will we be so codependent on these massive digital entities? Digital enterprise is no longer an experiment — it’s a legitimate business with large impacts on the consumer market and needs to be treated as such. On the security side, in light of data leaks like the Facebook Cambridge Analytica scandal that took place earlier this year, these digital companies have shown that while they have a massive presence, they don’t always have control over where their data goes, which is a major issue that needs to be addressed. Additionally, increasing amounts of people have shown distrust in being so digitally present or have removed themselves completely from social media platforms, so now is a crucial moment that will determine if living digitally dependent lives is sustainable in the long-term.

“Until these companies begin to take responsibility for what’s on their platform, it’s going to be complete chaos and anarchy. This is not healthy for democracy, and I don’t think it’s healthy for humans, as you can tell in terms of what I think about your addiction to your smartphone that it is probably not a good thing. It’s not making you smarter. It’s just making you more distracted,” said Taplin in an interview.

At the end of the day, the digital sphere can change intensely in only a short period of time. While one cannot be certain where certain digital platforms will be in the next two decades, one can know for sure that the digital market is here to stay. Now, it’s just up to consumers to decide how digitally codependent they want to be. The digital sphere may be prominent, but allowing it to have personal dominance is an individual choice.

Stacey Li

Stacey Li

Source:

Source: