In popular culture, the line “Follow the money” is associated with Watergate, when Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein tracked the cover-up of the break-in at the DNC headquarters all the way to President Richard Nixon. A similar version comes in the recent Broadway musical Hamilton, when Thomas Jefferson is pursuing salacious charges that will eventually ruin Alexander Hamilton: “Follow the money and see where it goes.” It is an apposite statement with regard to the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (fund). Today, firms across the world are asking where their money went in the case of the money-laundering Malaysian sovereign wealth fund. Following some initial investigations and findings, Goldman Sachs is in the crosshairs.

The investment firm, long one of the world’s most integral, has come under a barrage of criticism and rhetorical gunfire from Anwar Ibrahim, the likely future Prime Minister of Malaysia. After key Goldman partners were caught bribing and misleading significant Malaysian politicians as part of their dealings and bond underwritings with the country’s sovereign wealth fund 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), the firm has essentially been labeled “persona non grata” by Malaysia’s new ruling coalition. Goldman could lose out on numerous future contracts and the damage to its reputation will likely last for some time.

Anwar argues Goldman should return “significantly more” than the $600 million the bank was paid for arranging three bond sales in 2012-13 because “it’s a cost to the image of the country, it’s a cost to investments and now it’s a burden shouldered by the government because of the complicity of so many of these so-called credible, renowned financial institutions … For them to use a country like Malaysia — which is struggling to reform itself economically, moving up the ladder — really, to me, it’s disgusting.” [source]

The prime minister has said “aggressive negotiations” with Goldman are necessary, which may result in litigation or having the bank engage in information sharing to support the country’s ongoing probe of the fund.

Not only is Goldman under pressure in the country tainted by the scandal of its own prime minister furthered by financiers like the bank’s senior Asia partners, it is also under serious investigation at home in New York. The US Department of Justice is investigating as well. Goldman share prices have dropped, according to (rival) investment bank Morgan Stanley, by fourteen percent since it was reported that the bank was involved in the sleaziness.

Morgan Stanley analysts write that “It is unclear how long the issue will take to resolve, what the fines and penalties could be, and what costs Goldman Sachs will subsequently incur to satisfy any demands from regulators” [source].

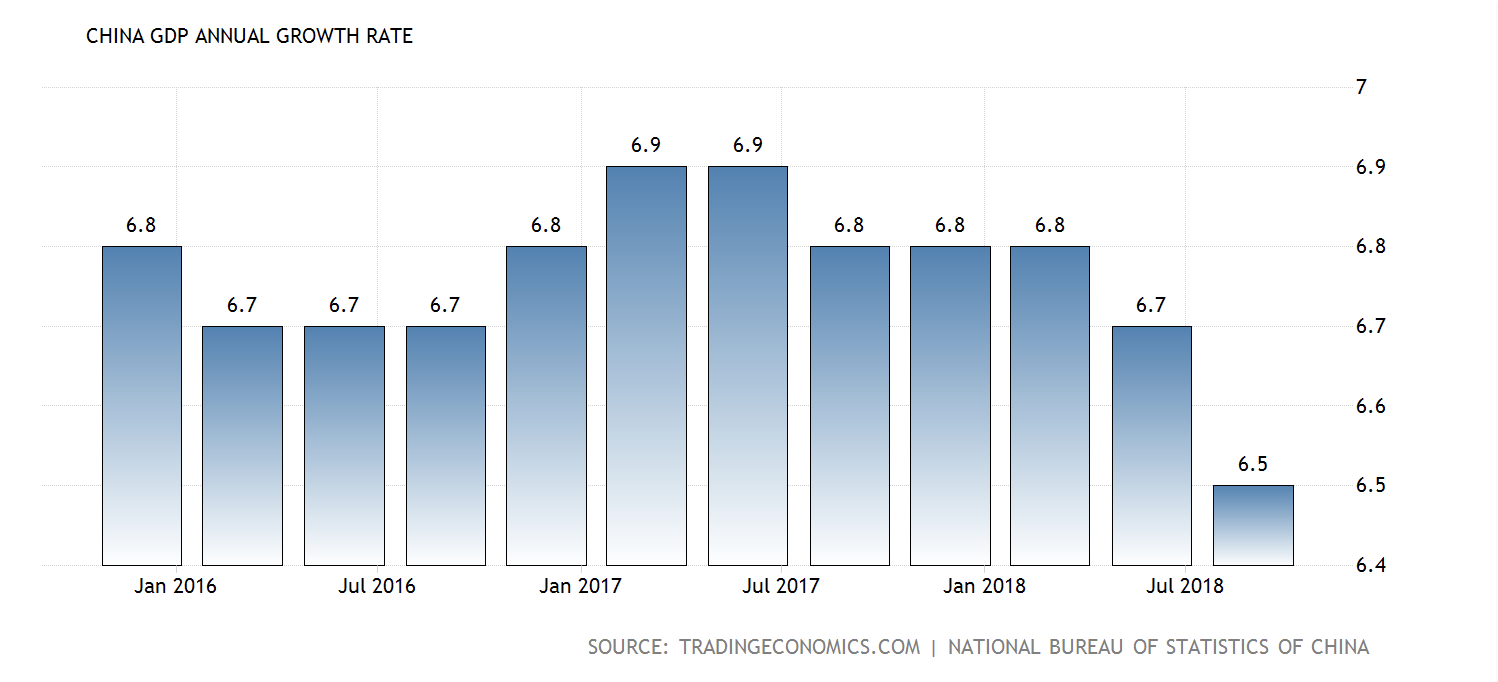

Currently, much of the infrastructure projects developed in conjunction with other nations by 1MDB is under review, and some have even been cancelled — including multiple China-backed pipeline projects. As part of the new government’s relatively icier China stance, the current prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, “suspended $23 billion in schemes linked to Beijing and criticised “lopsided” contracts as well as potential links to the scandal-ridden fund” [source] [source].

It is quite possible Goldman could be charged with a violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices act, and could face a fine of $1.2 billion, double the amount it made on bond underwriting for 1MDB. With the additional lawsuit against Goldman by Abu Dhabi’s own sovereign investment fund that is also wrapped up by the tentacles of the scandal, the bank could end up paying damages that “exceed Goldman’s average annual net profit over three years of $5.4 billion” [source]. While it remains to be seen how much Goldman will end up paying, it is clear the hit to its reputation and the three charges against former partners are just the beginning — the longer this scandal entangles Goldman, the worse it will get.