Amazon’s power over specific producer markets and Facebook’s dominance over advertising are eerily reminiscent of Standard Oil’s monopoly on oil in the late 19th century. By owning or controlling 90 percent of the U.S. oil refining business, Standard Oil was able to form trusts with other oil companies and drive out competition with others in the same business. Though Standard Oil was able to provide a quality product at a reasonable, stable price, the company uncomfortably wielded too much power in one of the nation’s most important industries. Ultimately, the government put antitrust laws into practice, breaking down Standard Oil’s trust and, ideally, preventing further monopolies from forming.

Now in the digital age, the large-scale presence of Amazon and Facebook isn’t as tactile as, say, oil, but that doesn’t mean their potential to monopolize isn’t as — if not more — dangerous. The way consumers interact with these companies may be primarily online, but their impact is both felt and seen in the real world.

World domination is taking on a more pixelated form. As these digital dominators revolutionize modern life — from making purchases to how people interact — many of their victims may not realize how dependent they’ve become. The relationship is reciprocal: These digital entities would not exist without consumers to collect information from, while consumers could not function in their everyday lives without these digital entities.

Yes, Amazon and Facebook are the culprits of seeking world domination, and the widespread economic impact they’ve had in the past two decades is both intriguing and alarming.

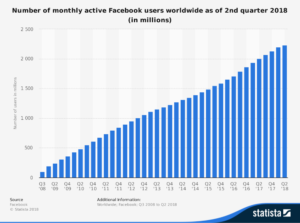

On one hand, the accessibility Amazon and Facebook provide have made modern life easier than in times past. Facebook has 1.6 billion active users. Amazon is predicted to end the year with 50 percent of the United States’ e-commerce market. Clearly, the two companies have an extensive presence in society. For the consumer, the instant communication and near-instant gratification offered by the digital sphere are shaping the ideal marketplace. This may be a great situation for consumers, but it doesn’t come without a cost.

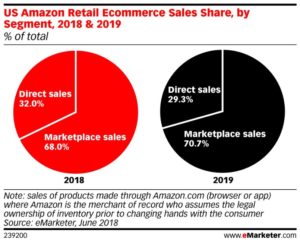

Amazon holds the largest portion of U.S. retail ecommerce sales. Source: CNBC

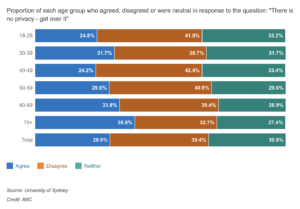

These digital companies buy users’ information in exchange for a curated service that is basically guaranteed to fulfill customers’ exact wants. Facebook especially has been accused of being an “ad-targeting machine” that tries to pass as a social networking site. Consumers, however, are unquestionably becoming increasingly dependent on these large digital companies to make economic decisions, with ambivalent feelings about online privacy. According to a survey of 1,600 people by the University of Sydney, over half of 18-29 year-olds agree with or are indifferent about the statement “There is no privacy — get over it.” Customers’ lives may be simpler by allowing Amazon and Facebook to take the reigns, but the grand digital dominance of these companies may prove more dangerous than anticipated.

Young people are conflicted about privacy in the digital age. Source: ABC News

Amazon, as most any digitally literate citizen knows, is an online retailer where consumers can buy nearly anything — anything — and have it shipped to their door. As discussed by Jonathan Taplin in his book “Move Fast and Break Things,” Amazon has created a monopsony over certain goods, which is essentially the inverse of a monopoly. A monopsony is when a buyer, as opposed to a seller in a monopoly, has control over who can enter a specific market to sell goods.

“Amazon has a near-monopoly position in the distribution of ebooks,” Taplin writes. “Beyond books, Amazon captures fifty-one cents of every dollar Americans spend in online commerce. It wasn’t supposed to be this way.”

Ironically, in 2014, New York Times opinion writer Paul Krugman published an article titled “Amazon’s Monopsony Is Not O.K.,” where Krugman dissected Amazon’s role in the ecommerce market.

“Amazon doesn’t dominate overall online sales, let alone retailing as a whole, and probably never will,” Krugman writes. “Don’t tell me that Amazon is giving consumers what they want, or that it has earned its position. What matters is whether it has too much power, and is abusing that power. Well, it does, and it is.”

Come 2018, research by eMarketer tells an updated story: Amazon now shares 49.1 percent of retail e-commerce sales, which is nearly 5 percent of the total U.S. retail market online and offline.

Further, Taplin points out that the main consequence of Amazon’s monopsony in the book business forces authors and publishers to work for less money. He details how Amazon is able to practice a form of “rent-seeking” by denying publishers access to its large customer base and extracting excessive “rents” from publishers because the company has driven out seller competition. Arguably, Amazon’s path to digital retail dominance came rapidly and without much question because of the convenience the company brought to consumers. As a result, however, the consequences of Amazon’s presence are only recently being studied.

VIDEO: Here’s Amazon’s impact on the economy

Beyond damaging competition with selling in the book market, Amazon has established other monopsonies that have had disastrous effects for classic physical retailers.

“Amazon has changed the market in many ways. By the end of this week, Sears will file for bankruptcy. That’s a direct result of Amazon. Kmart will file for bankruptcy probably within the next two months. There’s really no place for the old-fashioned retail to exist in a world where Amazon can undercut their prices,” said Taplin in an interview. “Amazon wants to rule the world. It’s simple.”

Facebook is a whole other beast.

As mentioned, Amazon holds a monopsony over particular retail markets, like ebooks. This makes it harder for other buyers to enter the market because Amazon’s prices are so competitive that any smaller seller would have a hard time being successfully profitable. Facebook, on the other hand, is the largest social network in the world with over two billion monthly active users or MUAs. The platform also owns Instagram and WhatsApp, which each has over a billion MUAs.

Facebook’s MUAs only continue to grow. Source: Statista

With such a large reach in the social media realm, Facebook has a near-monopoly on affinity side advertising, according to Dan Faltesek’s Medium article “Social Monopsony.” Taplin discusses Facebook’s business model in the same light, noting that the platform centers around selling advertising at a higher rate than comparable internet sites.

“In short, if you are looking to make a large social buy, Facebook is your only option,” writes Faltesek. “The case that Facebook has a near monopoly on in-stream affinity network advertising is fairly clear.”

The “Big Two” Facebook and Google control over 60 percent of internet advertising. No other online advertising platform has a market share exceeding 5 percent, according to Forbes.

Why is Facebook’s advertising scheme so successful? It’s simple: Microtargeting.

Microtargeting is a marketing strategy where a company collects specific information on consumers — where they live, what they like, what their friends like and so forth — and push advertising content their way that directly reflects their specific interests. While this can be an effective strategy for marketers, in a world where there is only one buyer of user attention, regulation is necessary, as Faltesek points out.

Based on the aforementioned details of both companies, Amazon and Facebook clearly have successful business models. In 2017, Facebook raked in over $40 billion in revenue while Amazon earned over $177 billion. Their overwhelming dominance, however, has taken a large toll on competition, which is essential for a free marketplace. With all other digital retailers fighting for a tiny portion of online advertising and physical stores being driven out of business because of Amazon, more regulation must be adopted to keep the marketplace stable and democratic.

“We’ve got ourselves a little challenge here in America: On one side you have Jeff Bezos and on the other side you’ve got democracy,” said director of the New America Foundation’s Open Markets program Barry Lynn in a New Republic article. “We can choose who we want to trust in. Do we want to trust in America and Americans and American history? Or do we want to trust in Jeff Bezos? That’s what this comes down to.”

As history has shown, the digital sphere has had a large societal impact despite evolving over a short period of time. Now, it’s just up to consumers to decide how digitally dependent they want to be.